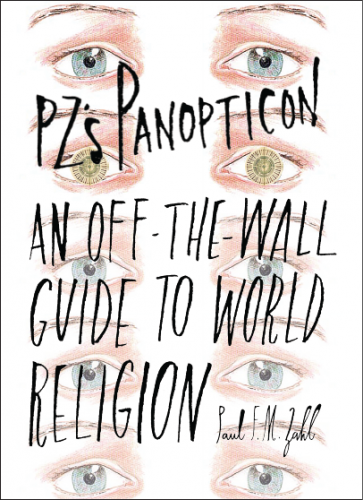

This quote comes from our inimitable purveyor of one-way love (and world religion!), Paul F.M. Zahl, in his latest work, PZ’s Panopticon:

“This guide to world religion is written through the lens of a near-death panopticon. It takes the position of a person who finds himself floating up the wall, on the ceiling, looking down helplessly as the surgeons try to save his body on the operating table…

“This guide to world religion is written through the lens of a near-death panopticon. It takes the position of a person who finds himself floating up the wall, on the ceiling, looking down helplessly as the surgeons try to save his body on the operating table…

Religion is not about the superiority of one concept in comparison to another concept.

Rather, religion is about salvation in the most imminent sense of the word. Religion is about saving your life, saving who you are from the defeat and extinction that death brings to your first subjectivity; and rescuing you, or some essence and aspect of you, in favor of some sort of continuity with who you were before you were born. Ideological secularism is a form of religion, too, by the way, because it is a thought-process about reality with a view to an absolutely solo dogged life that is exclusive to the exact period between your birth and your death…

Did you know that the origin of ghost stories is in the idea that the dead, or some of them, are still weighed down, almost literally, with things they have done in the past that won’t let them “move on”? Something like weights is preventing them from moving on to wherever they are moving on to. The ghost in supernatural fiction has something on his mind. It “weighs” on him or her so heavily that the ghost is held by it, suspended between life and whatever is beyond or after life. And the living, we, inter-act most reluctantly with the ghost who still has the work to do. In classic literary ghost stories, such as Edith Wharton’s “Afterward” or “The Beckoning Fair One” by Oliver Onions, the ghost gets “closure” by arranging for the evildoer from her or his life to be killed. Sometimes, though not as often, the ghost is benign, and helps an unrealized dream or hope of love to be realized, as in a mother’s dying wish for her daughter to be married or a husband’s dying regret in relation to his wife. When the past of the ghost is resolved, the “shade” of the ghost begins to fade away from involvement with its prior world. It is now at peace.

Our man on the cork ceiling is like a ghost. Or maybe not quite a ghost. But he thinks like a ghost. And the original, if faint, message of the world religion Christianity has something in it for him. It has something in it for ghosts everywhere, if only it can get through…

“Drawing a line through the past” – it is not only “closure”, it’s erasure – is exactly what a man or woman in near-death encounter desires to hear: “You can go now. That’s all forgiven and forgotten. It’s all right.” By this is meant, your past is taken care of and doesn’t have to be in front of you any more as you look ahead to what’s next. All is forgiven. Begin the beguine.

People get nervous about this, or at least people who are not in the middle of near death. It sounds from the vantage point of the other self, the person on the operating table, or rather, the patient in pre-op, like a blessing on bad behavior. You say to yourself, “How can that bad person get off the hook just because God chooses to disregard the things he or she has done and says, ‘Poof! All better now.’ When it’s all not better now.” I don’t know the answer to this question. It bothers me, too. But it doesn’t bother me much…

The mercy intrinsic to the teachings of Christ is something that is there from the beginning to the end. It is the crowning feature of what turned into the world’s most populous religion.

For quite a few people, there is something upsetting about the 100%-with-no-exceptions forgiveness that Jesus talked about. It is a feature that upsets conservatives. But it also upsets liberals. There is something in it to offend everybody. Except the person who needs it at the time.

What proves hard to swallow is the absolute character of it. Christ’s forgiveness includes the worst offenders you can think of, but it also includes the pussycats of life – there aren’t many pussycats, but there are a few – who have done nothing wrong or worthy of blame. It is a blanket forgiveness that puts a straight red line through the past. I write “red line” because the Old Story says that Christ’s blood was shed in place of my blood. Dylan captured this on his 2012 album “Tempest”: “I pay in blood/But not my own.” It seems obvious that this is unfair. It seems to put “The Good, the Bad and the Ugly” (1966) all under the same protection. There is no distinction.

A familiar rationalization for Christ’s universal forgiveness goes like this: “Well, yes, it is for everybody, but you have to ask for it. The offender can’t receive it until he or she asks for it. Each person, good, bad, or a little bit of both, has to do his part. It won’t do you any good if you don’t first come forward and take it.” That is a rationalization in service of explaining away the “full-service”, 24/7 gas station that Christ’s message actually is for all the cars on the road.

Can anyone really rationalize what Christ was saying when he said that people should be forgiven 490 times per action per person?

Yet that is exactly what the panopticon of life is seeing from its location in the hands of the person who is on the cork ceiling. Because there is no going back – it’s probably almost definitely over, downstairs – the forgiveness Christ was talking about when he said things like that has to be this way. For a person who cannot go back, mercy is everything or nothing. 490 times to be forgiven per person per action is just about enough.

So yes, we can mute it or explain it and even limit it if our panopticon is sited in the human world at ground-level. At ground level, I’m a believer: in “zero tolerance” and “one strike you’re out”. But for the man between, who is really the man “Afterward” (Edith Wharton), it is too late for that. It is either now or never. No more strikes allowed.”

COMMENTS

3 responses to “A View to a Death: Paul Zahl’s Christianity for the Dying”

Leave a Reply

“Well, yes, it is for everybody, but you have to ask for it. The offender can’t receive it until he or she asks for it. Each person, good, bad, or a little bit of both, has to do his part. It won’t do you any good if you don’t first come forward and take it.” That is a rationalization…”

Amen. Justification is not based on our lack of self-righteousness.We don’t need to travel through a “methodist” preparation to arrive at justification. Even though those who are justified do believe the gospel, God imputes Christ’s death to the elect without respect to their conscience. A justified conscience is a result and not a condition for justification.

Self-righteousness is the fruit of condemnation, and not the basis for it. We do not have to have an uneasy conscience in order for God to be at wrath with us because of imputed guilt. The guilty become self-righteous, yes, but guilt is not based only on our attitudes about God and the gospel.

Guilt is based on God’s external imputation, and justification is based only on God’s external imputation, on being “placed into” Christ’s death. Those who want to qualify and rationalize imputation express outrage at the idea that God could hate Esau before he was born (Romans 9)

God is seen to be horribly unjust to condemn those who “don’t even have a chance” at escaping original sin.

One example of the “respect of persons” which God forbids is the rational idea is that nobody should be condemned “merely” because of the imputation of Adam’s sin.

Not illogical, Mark – but I loved this excerpt’s “mercy for the dying person” theme, too. The “systems of grace” debate is an interesting one, with many cogent alternatives (including yours), but I think secondary here. Not to argue on it at all: as the old adage goes, “once you get into double predestination… you never get out”