[Books are] a children’s game which God has given me in order that the time till his appearing should not be long for me.”

~ Johann Georg Hamann

William Hale White: He wrote under the name Mark Rutherford and all his books, like his life, reflect the tension of being never quite able to either hold on to nor let go of the “comfortable words.”

William Hale White: He wrote under the name Mark Rutherford and all his books, like his life, reflect the tension of being never quite able to either hold on to nor let go of the “comfortable words.”

- The Revolution in Tanner’s Lane

– an unnerving description of the way “theology” can fail to help at the crossroads of honest questions and tragedy.

- Bonus: J.D. Salinger, Franny and Zooey – the gap between knowledge and wisdom can be fatefully wide. Can Jesus help? “Lord Jesus Christ, have mercy on me a sinner.”

- Catherine Furze

– an honest and omniscient book about the volcanic eruptions that are possible as a result of (sexual) repression and emotional lack. Oh, and forgiveness can change the world.

- Clara Hopgood – honest and tragic; love almost but never. And death. But: (maybe) hope.

- Miriam’s Schooling – Luther said we learn in the “school of experience (or life).” This story says that too.

- The Revolution in Tanner’s Lane

- Tolstoy

- Father Sergius –exposes the vanity of so much piety and yet points to something real: humble and quiet love.

- “Where Love Is God Is

” – by the end Tolstoy was writing short stories as echoes of Jesus’ parables; this is among the best, especially the scene with the grandma and the little boy.

- Bonus: “How Much Land does a Man Need?” – hint: the answer is six feet; enough to be buried in.

- The Death of Ivan Illych – Of course I’m not going to die. That’s what I think…except when I’m reading this novella.

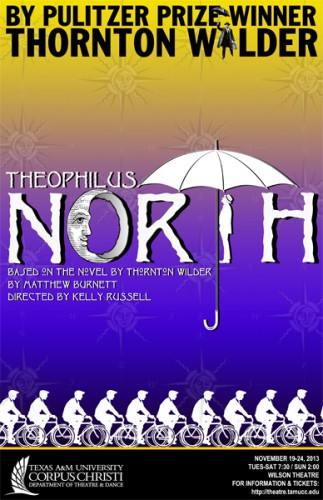

- Thornton Wilder

- Theophilus North – the charming tutor, trickster, coach, companion, and gypsy offers, in the course of one summer of interactions, a course in pastoral care.

- The Bridge of San Luis Rey

– art: it asks and asks and asks a question that it never pretends to be able to answer.

- The Angel that Troubled the Waters: a three-minute play that near the end, with the voice of an angel (literally), says it all. Hint: St. Paul said something similar in 2 Corinthians 12:9-10. Wilder said he was looking for “new persuasive words” for the old, old message: this play found them.

- Poetry

- Percy Bysshe Shelly, “Epipsychidion” – What’s love got to do with it? Um: maybe everything

- Samuel Johnson: “The Vanity of Human Wishes” – disillusioning, but with an (Ecclesiastes-like) honesty that clears the ground for meaning and hope. Diagnosis: “When first the college rolls receive his name/The young enthusiast quits his ease for fame/Through all his veins the fever of renown/Burns from the strong contagion of the gown”

- Oscar Wilde, “The Ballad of Reading Gaol” – like a meat tenderizer hitting my rocky heart: “Ah, happy they whose hearts can break/And peace of pardon win!/How else may man make straight his plan/And cleanse his soul from sin?/How else but through a broken heart/May Lord Christ enter in?”

- Somerset Maugham, The Razor’s Edge

– Larry witnesses a death (“I’ll be jiggered!”) and the futility of the status quo is suddenly obvious. But what is real and true and worth living for? That’s Larry’s question, and the reader gets to listen to him ask it.

- Bonus: Jack Kerouac, The Dharma Bums – another couple of guys who are devoted to learning what is real. Interestingly, their “answer” is similar to Larry in The Razor’s Edge. In both cases it’s the question more than the answer(s) that shook (and helped) me.

- Philip Wylie, The Disappearance

– in an instant the men disappear from the women and the women disappear from the men. A diagnostic and almost prophet reflection on sexuality and gender (and much else besides).

- Booth Tarkington, The Magnificent Ambersons

– my first Tarkington novel, and he is a master. This won the Pulitzer Prize in 1919. Duh. Tarkington is deep inside human existence and their intractability. The plot (and people) hit a wall. The resolution: a bizarre, spiritual non sequitur that not even the Orson Wells movie could capture but which to read is to believe.

- George Eliot, Janet’s Repentance

– from her Scenes of Clerical Life. When Janet (an abused, drinking, and despairing woman) and the minister, Mr. Tryan, really talk (“sinner to sinner,” Eliot says), it is the quintessential form of preaching—and it actually helps.

- James Gould Cozzens, By Love Possessed

– an all-seeing eye, this book is written from inside human experience: emotions, internal dialogues, memories, projections, hopes, fears… Not much happens, but everything is known and said.

- Bonus: Marilynne Robinson, Lila – a raw and beautiful book, whose real achievement, as I see it, is that it is consistently told from inside the heart and eyes of Lila and is, in that way, an invitation to live and feel with another.

- Double Bonus: Samuel Johnson’s critical introduction to Shakespeare celebrates him as an artist for the very reason Lila and especially By Love Possessed are art: the Bard holds up a mirror to human existence and lets us watch ourselves; he tells us what we need to know but do not: who we are.

- Irvin S. Cobb, “The Lord Provides

” – a plain style that moves to a moment that only mercy can heal.

Note: On reading theology this year

It’s the questions as much as (and often more than) the answers that have hurt and helped this year. So: Johann Georg Hamann, perhaps history’s greatest reader and one who was able to always remain a child without the curses that plagued Peter Pan (i.e., a lack of love, both familial and romantic, and self-absorption). Rowan Williams can unsettle easy answers and leave you with new and deeper questions. I keep reading William Hale White’s fiction because his life and writing are a question mark in the form of prose. Wilfred Stone’s Religion and Art of William Hale White captures the whence of Hale White’s questions and helps in the attempt to hear what if anything he found by way of answers. Also, if you want your assumptions about what it means to read a text or encounter art to be smashed against the rocks, read Oscar Wilde’s “The Critic as Artist.” This dialogue is a treasure-chest of help: I just don’t know what that means (yet). And of course, the gift and gadfly that is PZ’s Panopticon: Death—can your or any religion help?

The question that shapes Paul Zahl’s book feels, in retrospect, like a thread tying a lot of this year’s reading together. Unanswered questions haunt, and death either raises them or is them. The reading that has meant the most this year has been those books, poems, plays, or whatever that ask the questions, whatever they may find to say (or not) in terms of answers. But PZ’s Panopticon does seem to ask the real question and speak the adamantine (and only) answer: Can anything help, Death asks. “A different me, and a great Amnesia from God.” Or, as I might distill the sentence: Jesus.

COMMENTS