1. If you weren’t already following the lengthy award-show season, let it be known that the Oscars are this weekend. Tis the season for actors, directors, writers, cinematographers, etc., etc., to fight for golden trophies that only weigh 8.5 lbs. but carry a heavier significance. One Academy Award (or even nomination) can change the way an actor is perceived. Leonardo DiCaprio is no longer just Leonardo DiCaprio; he is Academy Award © Winner Leonardo DiCaprio. It isn’t enough that a movie does well at the box office, the next (and even bigger) goalpost is that of Academy recognition.

But to win an Oscar, you apparently have to campaign for it, and we’re talking the whole ordeal — appearances, interviews, campaign strategists, media marketing, and voting. Look no further than the most recent GQ or Times magazine covers and you’ll find two Oscar nominees fighting their way for center stage. But as much as the nominees may want an Oscar, they don’t ever want to look like they want one that much. Michael Schulman, for the New Yorker, exposes the paradox of award campaigning:

To campaign for an Oscar, as for the Presidency, you need a narrative — some compelling story, decided on by a combination of the nominee, campaign strategists, and the media, that gives voters a warm, happy, check-the-box feeling. Underdog stories often work. Last year,“Everything Everywhere All at Once” was the Little Movie That Could. Its leading lady, Michelle Yeoh, was the Seasoned Star Who Has Never Got Her Due. Her co-star Ke Huy Quan was the Former Child Actor Making an Emotional Return. And their castmate Jamie Lee Curtis was Hollywood Royalty Who Will Not Cower at Being Called a Nepo Baby.

If dedication, often in the form of hours logged or special skills mastered, is a key ingredient, so is authenticity. […]

But there are hazards. To paraphrase Ferrera’s “Barbie” speech, Oscar campaigning is a paradox: you have to be extraordinary, but, even if you’re on-message and game, you can somehow leave the impression that you’re doing it wrong. Fairly or not, Cooper has been pegged as this year’s Try-Hard Who Wants an Oscar So Badly That We Should Probably Just Give Him One to Prevent a Psychotic Break. In Vulture, Nate Jones observed that “Maestro” has become this year’s “Oscar Villain” — the movie that you start to root against as it glides toward glory.

There’s nothing, dare I say, cringier than a try-hard. A try-hard is the opposite of an underdog, which makes them harder to root for. No matter how hard they try (or attempt not to try) award season is proof that the goalpost is always moving — even for those in the audience.

2. Campaigning for the self is not a new practice. We may not have paid strategists to work on our compelling narrative, but we do have personality assessments to ascertain our strengths and marketability. Unlike the late nineteenth century (where philosophers, like Nietzsche, claimed that we were unknowable to ourselves), the twenty-first century seems to be a ripe time for self-awareness and self-understanding. To know thyself is to know one’s own significance, as to navigate the world properly. There’s a reason many of the stories today — both real and fictional — center around identity (Paul Atreides, I’m looking at you). But is it possible to fully know ourselves through the various personality tests available to us? Christopher Yates, for the Hedgehog Review, argues that the answer is no:

Consider first, for context, the subtext to “progress.” Sometimes new advances on old advances enhance our ability to forget the leaps of faith taken in the early days. What start out as qualifying statements become parenthetical caveats, which then shrink to ellipses, which in turn become periods, then acronyms. Guesswork becomes confident; speculation turns to certainty; possible fallacies become matters of fact. We mistake impressions for absolutes. As applied to what our genealogy has revealed, the person becomes a personality, and personality — in principle, a conditional abstraction — becomes an ascertainable essence. The self is flattened into a brand without mystery. Dostoevsky frets that, beholden to the calculative and classificatory, “all possible questions will vanish in an instant, essentially because they will have been given all possible answers.” The promise of answers is compelling. Maybe personalityism offers a clinical third-party perspective on ourselves in a world where we don’t trust real people to do this. Maybe we consent to being abbreviationally sorted because of that existential restlessness to which Goethe’s young Werther confessed: “How we crave for a noticing glance!” After all, to be sorted is to be noticed in a way, to be specified and thereby ratified. It answers a human need.

Answers, of course, sometimes reveal things about those who find them. Whatever we may think we know of ourselves in our preinventoried state, we sense that we are indeterminate until some instrument determines us. “The whole human enterprise,” Dostoevsky continues, “seems indeed to consist in man’s proving to himself every moment that he is a man and not a sprig!” The proof comes when we are recognized, which today means codified. The phrase “We’ve processed your inventory” tempts us with significance, and we are not wrong to desire that. Being a self is a difficult business. But when we abbreviate ourselves through the instrument-driven order of operations, we also abbreviate, or even skip entirely, what needs to be a long and probing engagement with that difficult condition. […]

The personality assessment regime to which so many eagerly submitted did not just improve management or propel new clinical research lines — it salved an existential wound. By codifying the individual, it shortcut the unexpectedly long haul of internal reconfiguration.

Perhaps self-understanding can answer the lifelong question of our purpose on this floating rock in space. But that answer will always be lacking in comparison to our identity in Christ. Self-justifying traits like competence, independence, or openness are as temporary as they are helpful. When we die and reach the pearly gates of Heaven, God won’t be asking us about our Enneagram type.

3. Speaking of death and identity, there’s no better time to reflect on our mortality than during the season of Lent. Coming up on the fourth week in Lent, the New York Times’ Molly Worthen interviewed college students on what Lent means to them:

When I called up current students and recent graduates from Christian colleges, most of whom started taking Lent seriously only when they got to college, they described the surprising freedom they found in submitting to tradition. I asked about sin and the English Puritan John Owen’s command to “load your conscience; and leave it not until it be thoroughly affected with the guilt of your indwelling corruption, until it is sensible of its wound, and lie in the dust before the Lord.” They pointed out that the call to self-mortification is not an end in itself. Lent is a time to repent of worshiping false idols, yes — in order to reorient the impulse to worship. The aim of the hunger pangs is to drive home your dependence on God; the structure of tradition is a tool for that. […]

Ms. Reed, who now works as a freelance writer in Waco, explained the paradox of feeling freer during the rule-bound Lenten season: The rules rescue you from the pressure to pretend you are a totally autonomous being. “We live in a culture where you can have every comfort and an extremely high level of self-determination relative to history. You can do what you want with your time and money,” she said. “In that context, taking on Lent is a powerful reminder that you’re a finite, weak creature who has to eat multiple times a day to stay alive. The true nature of our presence in this world is extreme dependence.”

And what of our identity?

Lent, then, is not about groveling in repentance for one’s sins but understanding sin in the context of “hope in the Resurrection and Christ’s mercy” — which Ms. Surdyke sees as a powerful response to the clichéd college quest for personal identity. “Identity is such a prominent theme in our culture. Everyone is so desperate to know who they are,” she said. “I believe you cannot know who you are unless it’s in relationship with Christ, because he made you, he defines you.”

Young adults’ desire for more traditional structures within the Christian faith seems strange in the age of Evangelical mega-churches. But I have spoken with multiple peers who find the liturgy of some services to be more meaningful than the usual praise band. With the self-care-ification of religion (to say nothing of Christian nationalism!), young people want to believe, not in that which asks something of them, but that which tells them the truth of who they are. When multiple hands pull for our attention, what we really want are the hands of God that hold us in our frailty.

4. What if background checks went deeper than speeding tickets and credit checks? What if a background check could share what your Spotify wrapped actually was instead of what you pretended it to be? What if a background check revealed the photos of you in middle school that you thought you deleted from your mom’s FB page? (Have they made a Black Mirror episode about this yet? If so, drop the rec pls). Either way, Points in Case dared to wonder about the what if’s:

Well, Mr. Horgenfliegen, under normal circumstances, we’d be happy to offer you employment here at Waterhouse, Waterhouse, and Waterhouse. After all, your CV is excellent, your cover letter is in English, and you attended the same theatre camp as our CEO.

However, when we ran our routine background check, we found something alarming.

Apparently, when you were eleven years old, you said you had to go to the bathroom during church, but instead you stole three bags of Werther’s Originals that were stashed in the office cabinet. And when it was brought up at the next Sunday service, you let Paul Beerus blame the janitor over and over until they finally agreed to replace her with a fleet of Roombas.

Naturally, such a scandalous action would cast a pall over the entire organization, so we will be terminating our offer of employment forthwith. We trust you will find a workplace more suitable for your personality. Like WalMart.

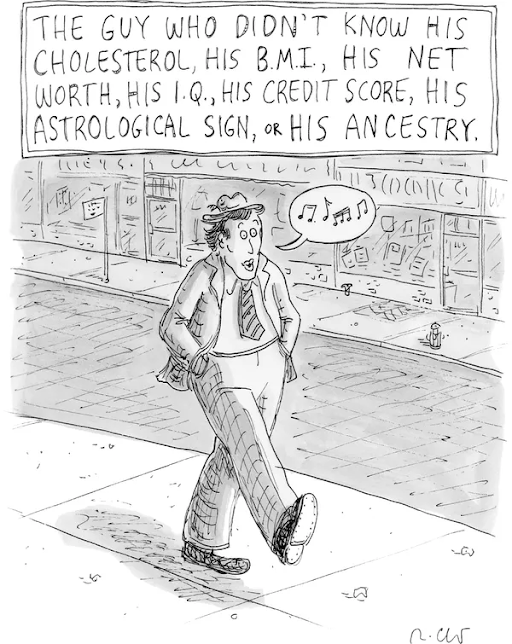

If today is a day of Murphy’s Law, find camaraderie in Reductress’s “It’s Always F**king Something.” And finally, for kicks and giggles, it wouldn’t be AWE without a fresh cartoon from the New Yorker:

5. Next, the Wall Street Journal published a fascinating piece by Rob Henderson entitled “‘Luxury Beliefs’: That Only the Privileged Can Afford.” Henderson, who didn’t have the traditional affluent background like most of his Yale peers, noticed that the upper echelons of students communicated their status by broadcasting approving stances on social issues they would otherwise not endorse for themselves. What used to be a showcase of expensive material goods became a form of virtue-signaling:

Today, when luxury goods are more accessible to ordinary people than ever before, the elite need other ways to broadcast their social position. This helps explain why so many are now decoupling class from material goods and attaching it to beliefs. […]

When my classmates at Yale talked about abolishing or decriminalizing drugs, they seemed unaware of the attending costs because they were largely insulated from them. Reflecting on my own experiences with alcohol, if drugs had been legal and easily accessible when I was 15, you wouldn’t be reading this. […]

It is harder for wealthy people to claim the mantle of victimhood, which, among the affluent, is often a key ingredient of righteousness. Researchers at Harvard Business School and Northwestern University recently found evidence of a “virtuous victim” effect, in which victims are seen as more moral than nonvictims who behave in exactly the same way: If people think you have suffered, they will be more likely to excuse your behavior. Perhaps this is why prestigious universities encourage students to nurture their grievances. The peculiar effect is that many of the most advantaged people are the most adept at conveying their disadvantages. […]

But negative social judgments often serve as guardrails to deter detrimental decisions that lead to unhappiness. To avoid misery, I believe we have to admit that certain actions and choices, including single parenthood, substance abuse and crime, are actually in and of themselves undesirable and not simply in need of normalization. Indeed, it’s cruel to validate decisions that inflict harm. And it’s a true luxury to be ignorant of these consequences.

In AWE a couple months ago, we featured an essay by Richard Beck that called into question the elite’s criticism of the prosperity gospel. Critiques of the prosperity gospel seemed like good news but only to a certain demographic of Americans. To those experiencing poverty or lower income, Beck concluded, the prosperity gospel offered tangible hope. Similarly, if we critique social issues as if we have all the right answers, it might come at the expense of the people actually being served by such social causes. Instead of steamrolling out our hot takes or political positions, maybe we can lay them at the foot of the cross and let God do the work of healing.

6. To close, Mike Cosper wrote a timely essay for Comment Magazine on the church’s abuse of authority. A famous example of this, Cosper shares, is when the seventeenth-century church wrongly accused and condemned Galileo of heresy when he published The Starry Messenger (a publication that they believed challenged the Bible’s authority). The church’s abuse of power is nothing new to the twenty-first century, one glance at the news would propagate several instances in which the church failed its congregants and fueled its controversies. What, then, is a balm against this threat of violence?

In the devastated spiritual landscape of the twenty-first century, where lack of community and lack of meaning are the normal experience for most Americans, and where performative rage dominates our cultural and political life, building a community of love sounds quaint. But it is precisely love’s countercultural and counterintuitive nature that makes it so powerful. As Guy Garvey puts it, love is the original miracle. Love is a source of authority we know from our everyday lives.

The apostle Paul warns us that if we have everything but lack love, we have nothing. I take that as both a spiritual reality — that it’s a key to the good life for an individual person — and a political reality — that it’s a vision for a flourishing community. Because of that, I also believe that the church’s diminished place in the world shouldn’t trouble us so long as we have — or can resurrect — love.

Imagine if we possessed all that we think could cure our crises, both inside and outside the church: power and influence in politics, the academy, the marketplace, the entertainment and media industries. Imagine if we had a place at the table in discussions of economics, philosophy, the natural sciences, or medical ethics. If we had all of these, but didn’t have love, what good would we be? Moreover, how long would we last in those places and at those tables, if we showed up with all the right answers and no love? […]

There is something lamentable about this, given that much of what is good and worth advocating in the Judeo-Christian tradition is open to debate in ways that

were unimaginable in previous eras. But there’s something liberating about accepting it as fact. We no longer need be tempted to calculate for the preservation of authority or the accumulation of power in our moral considerations. Instead, we’re left with a relatively simple and straightforward command. The command was given by Jesus, when asked what was the greatest commandment. He answered: Love the Lord your God with all your heart, mind, soul, and strength, and love your neighbour as yourself. Not only is this the best guidance for preserving a clean conscience; it’s the only real path to establishing a new basis for authority in the

new world that is being built before our eyes.

Strays:

- In the New York Times, find Francis Spufford’s review of Marilynne Robinson’s Reading Genesis

- Melissa Florer-Bixler, in the Christian Century, on “Spending Lent with people in recovery.”

- “Idols or idiots? Why sporting stars cannot bear the weight we place on them“

COMMENTS

Leave a Reply