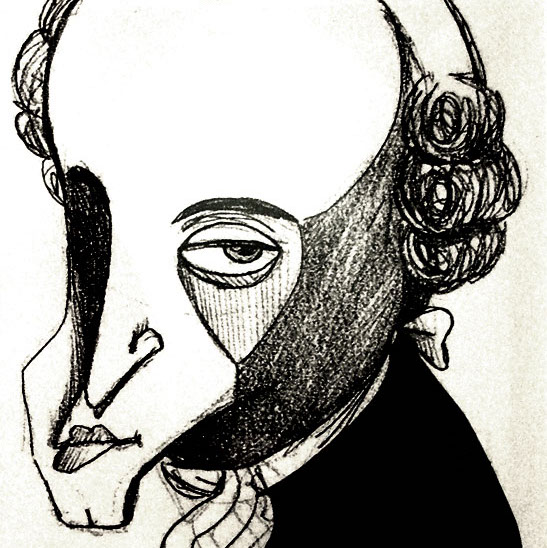

There was an interesting article in the Gray Matter column of this past Sunday’s Times. The article, written by philosophy student Paul Henne and social science researcher Vlad Chituc, take a look back at one of central ideas of Immanuel Kant, the 18th century German philosopher who is also considered to be the central figure of “modern philosophy.” He is known for his moral philosophy, and specifically his understanding of the “categorical imperative,” that moral laws–if they exist at all–must exist universally and necessarily. Kant also believed that a prescriptive law, by definition, implies that it can be followed/achieved.

In their article, “The Data Against Kant,” Henne and Chituc argue to the contrary: just because we ought to do something does not mean that we can actually do it. Using a social science experiment from the 80s, they argue that, much of the time, when we think about moral imperatives (“ought” or “should”) in our lives, those imperatives are categorically impossible. The law, instead of being predicated on one’s ability to achieve it, is instead predicated on one’s latent obligation/blame. We “ought” to do something–even if we can’t–because we are to blame for not being able to do it. Here’s the (pretty muddy, if you ask me) example:

Suppose that you and a friend are both up for the same job in another city. She interviewed last weekend, and your flight for the interview is this evening. Your car is in the shop, though, so your friend promises to drive you to the airport. But on the way, her car breaks down — the gas tank is leaking — so you miss your flight and don’t get the job.

Would it make any sense to tell your friend, stranded at the side of the road, that she ought to drive you to the airport? The answer seems to be an obvious no (after all, she can’t drive you), and most philosophers treat this as all the confirmation they need for the principle.

Suppose, however, that the situation is slightly different. What if your friend intentionally punctures her own gas tank to make sure that you miss the flight and she gets the job? In this case, it makes perfect sense to insist that your friend still has an obligation to drive you to the airport. In other words, we might indeed say that someone ought to do what she can’t — if we’re blaming her.

Three decades after Professor Sinnott-Armstrong made this argument, we decided to run his thought experiments as scientific ones. (We partnered with Professor Sinnott-Armstrong himself, along with the philosopher Felipe De Brigard.) In our study, we presented hundreds of participants with stories like the one above and asked them questions about obligation, ability and blame. Did they think someone should keep a promise she made but couldn’t keep? Was she even capable of keeping her promise? And how much was she to blame for what happened?

We found a consistent pattern, but not what most philosophers would expect. “Ought” judgments depended largely on concerns about blame, not ability. With stories like the one above, in which a friend intentionally sabotages you, 60 percent of our participants said that the obligation still held — your friend still ought to drive you to the airport. But with stories in which the inability to help was accidental, the obligation all but disappeared. Now, only 31 percent of our participants said your friend still ought to drive you.

I’m not so sure that this necessarily demonstrates the opposite of Kant’s conclusion. After all, Kant was arguing that laws are laws because they prescribe a way of living that can and should be attained. The friend who punctured her own gas tank broke the law here–she could have and should have taken her friend to the airport–and thus remains indebted to her ‘ought.’ But, following along with Henne and Chituc, the psychological backdrop of “blame” in the can/ought system is really interesting, especially if you’re reading any St. Paul: Psychologically, we do tend to think about moral laws as debts to pay for a blame we carry. It doesn’t sound too different from the “ministry of death” described by St. Paul: “The sting of death is sin, and the power of sin is the law.” The blame we feel must be shed from us is carried out in the law we hope to fulfill.

In Romans, Paul talks about the Jewish law of circumcision. He tells them that their circumcision is null and void if they are not also perfectly righteous and blameless before God. They continue to stand “blamed” by the perfect offering they cannot present to God. Paul then speaks of the blamelessness that can only happen within, and then he describes the only way the “ought” from the can/ought system can be taken. This, Paul says, “is given through faith in Jesus Christ to all who believe.” In Christ, no one can, though everyone ought, “for all have sinned and fall short of the glory of God,” but “all are justified freely by his grace through the redemption that came by Christ Jesus.”

COMMENTS

2 responses to “Even Though I Ought To…I Kant!”

Leave a Reply

The thing that I understand about Kant is that there is no break from one’s moral obligation because they are self-employed, but rather only a progressive ability to fulfil them in an unending post mortem existence. This is because God, immortality and freedom only exist in his critical philosophy as ideas of reason, rather than as phenomena in the world. In a relatively famous essay, Kant avec Sade, psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan showed the perverse relationship Kant’s moral philosophy enjoyed with its opposite (the philosophy of the Marquis de Sade), whereby the desire for greater moral fortitude provokes the desire for greater perversity, pain and pleasure. Paul’s theology cuts right across this dialectic, because it totally disarms desire, for good or evil, by exposing the relationship the law has with sin and death. This theology scrambles (or intervenes in) our notions of law and the infinitely receding desire to do good, through our identification with the God who became sin in the eyes of the law. In our identification with Christ (the scum of the earth), rather than with the law, the desire to “be good” becomes impotent. We can be good, but only because we don’t have to be!

http://www.nytimes.com/1997/10/05/books/monkey-business.html

Ed Larson, Summer for the Gods

William Jennings Bryan—-we will be buried by the “survival of the fittest” ideology of Darwinian capitalism

https://www.vox.com/the-big-idea/2018/3/5/17080470/addiction-opioids-moral-blame-choices-medication-crutches-philosophy