This interview was originally published in Sleep issue of The Mockingbird magazine.

If you’ve ever taken a retreat at the Abbey of Gethsemani, you may not remember exactly what you did, but you’ll remember how it made you feel. Its atmosphere of lush silence is unforgettable, and delicious to the soul. As described on its website, Gethsemani offers “a place apart” where one can “entertain silence […] and listen for the voice of God.” At the very least, that always makes it a much-needed respite from the frenetic bustle of modern life.

Nestled deep in the hills of central Kentucky, the Abbey is a monastery of the Order of the Cistercians of the Strict Observance (OCSO), known commonly as the Trappists. It was founded in 1848 and is the oldest Cistercian monastery operating in the U.S. Like all Trappists around the world, the 40 or so monks at Gethsemani strictly observe the Rule of Saint Benedict — a guidebook for communal monasticism composed in 516 A.D. — and are famous for their commitment to quiet contemplation, sometimes even resorting to sign language in order to minimize the need for spoken words as they fulfill their basic duties of prayer and work (“ora et labora”) in service to Christ. With over 2,000 acres of rich woods and farmland, the Abbey runs a 30-room guest house for retreatants and funds itself primarily through its store, Gethsemani Farms, which sells bourbon-infused fruitcakes and fudges made by the monks.

Of course, Gethsemani is best known as the longtime home of Thomas Merton, who lived there as a monk from 1941 until his death in 1968. Merton gained widespread and unlikely fame with the publication of The Seven Storey Mountain (1948), one of the best-selling religious autobiographies of the 20th century, which describes his conversion and winding path to the monastery. The book helped fuel a mid-century surge of interest in monastic life, but is only the most famous of dozens of works of religious literature, poetry, and social criticism that Merton authored, including No Man Is an Island (1955), New Seeds of Contemplation (1962), and Conjectures of a Guilty Bystander (1966).

One of Merton’s many novices as novice master at Gethsemani was Brother Paul Quenon, a West Virginia native who entered Gethsemani at just 17 years old in 1958. Over the decades, Quenon has held various jobs in the Abbey community, including operating the mimeograph machine, polishing the floors, and cooking in the Abbey kitchen. But he has also followed in Merton’s footsteps as an author of numerous books relating to his life as a monk, including his book of poems Unquiet Vigil (2014) and his recent memoir In Praise of the Useless Life (2018), referenced heavily below. In July, he graciously agreed to speak with us by phone about his life as a “nighttime hermit.”

Mockingbird: Br. Paul, you’ve been at the monastery for over 60 years now. What promptings first led you into this unusual way of life?

Paul Quenon: Well, I went to a Catholic school through high school, although that didn’t particularly inspire me. But then I read The Imitation of Christ, which is a devotional classic of the 15th century — Thomas à Kempis is the reputed author. And I read The Seven Storey Mountain by Thomas Merton. It was the combination of those two books that led me here.

M: I’m sure you weren’t the only person that ended up in the monastery after reading The Seven Storey Mountain.

PQ: Oh yeah, there’s been plenty. I also read The Brothers Karamazov by Dostoyevsky. I was inspired by the third brother Alyosha, who entered a monastery.

M: So it was a very literary journey for you?

PQ: I guess you could say that.

M: One of the things that distinguishes monastic life is the Liturgy of the Hours — or Divine Office — which is a series of communal prayer services that occur at specific times every day. The first one, I believe, is Vigils at 3:15 a.m., followed by Lauds at 5:45 a.m. I know you also wake up at 2:40 a.m. for your first private meditation of the day. Perhaps I’m just clueless, but with that schedule, how do you ever get good sleep?

PQ: Well, I do take a half-hour siesta after lunch and that brings me close to seven hours of sleep a day. Now that I’m close to 81 years old, I’ve also started taking a 15-minute nap before Lauds.

M: How strict are you with your schedule? Do you ever skip a service, or maybe sleep through your alarm?

PQ: I have slept through my alarm a few times, but usually I’m pretty regular about attending the Offices.

M: In your book In Praise of the Useless Life, you actually say at one point that if you miss a service, something feels off for you.

PQ: Yeah, but that’s just a personal response. If there’s a good reason for missing it — if I have to go to the eye doctor or something like that — it’s not something I worry about. It just happens, you know. If I’m away from the Abbey, I often say the Psalms as I’m driving. I know all the Psalms in the Little Hours.[1]

M: That’s remarkable. Memorization is so foreign to my generation, unless you’re an actor or something. Everything is available to just look up really quickly, so there’s so little impetus to memorize things.

PQ: Yeah. Lately, I’ve actually been working on memorizing part of a poem by Wordsworth: “Our birth is but a sleep and a forgetting: / The soul that rises with us, our life’s Star, / Hath had elsewhere its setting.” Do you know that one? I thought that might be relevant to your research on sleep.

M: That’s beautiful.

PQ: It’s one of his more famous passages, but it’s in an almost endless poem.

M: I’m interested in the spiritual significance of the name Gethsemani. In the Bible, of course, it’s a place associated with night — the night before Good Friday — when the disciples kept falling asleep while Jesus stayed up praying and agonizing over his impending death. Where do you find yourself in that story?

PQ: Well, that’s the phase of Jesus’s life that, in a way, defines what we are as monks and as members of this community. The crucifixion was the physical anguish of Jesus, but then there was the mental anguish that he felt in the Garden of Gethsemane, and so I think that’s part of our participation in the sufferings of Christ — when the mind participates in that. Part of the prayer life is simply to share the anguish of people, people like the Ukranians, who are getting everything taken from them. You know, I can’t do anything directly, but I can remember them. I’ve found that people appreciate it if they know that someone is remembering them.

M: Another thing that really distinguishes life at Gethsemani is of course how quiet it is. There are signs all over the place that say things like “Silence is spoken here.” Why is silence so meaningful to the Trappists?

PQ: It fosters meditation. Silence is the atmosphere of the monastery, and it helps to enable interior communion with the Lord.

M: In your book, you say that monastic life is essentially “a vacating, … a personal emptying out of clutter within the mind and heart…to make room for God.” Is that also what sleep can do?

PQ: I think sleep is a way of disconnecting. You’re not driven by the pressures of the day while you’re asleep. In dreams, one of the things that happens is that you replay the day, but your mind is free to break all the rules while it replays scenarios. A lot of times you dream basically some version of what happened the day before. But there is also an emptying in sleep, especially if you go down to Delta; you know the different levels of sleep, no doubt.

Delta is the kind of sleep I talk about in my poem “Sleep Deficit,” where I wake up and don’t know where I am or what time it is: “I wake to briefly knowing not / place or time […] / knowing pure, refreshing kindness / of knowing not.” That’s an indication that I have been in Delta, and you know, the Hindus say that that’s the closest thing to Enlightenment in the natural order of things. That dreamless sleep is very close to Enlightenment.

M: I guess, in that sense, sleep could even be a form of prayer — or a kind of poor man’s meditation?

PQ: Well, I think it empties the mind, and to that extent it can be. But of course when you have dreams, then there’s more stuff that goes into your consciousness, although we forget most of our dreams.

Untitled (Self Portrait), 1958 by Ralph Eugene Meatyard. ©The Estate of Ralph Eugene Meatyard, ©Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco. The photographer Ralph Eugene Meatyeard was a regular retreatant at the Cistercian Abbey of Gethsemani, where he befriended Thomas Merton in 1967. The two men shared a deep friendship and creative dialogue that would last two years, cut short only by Merton’s untimely death.

M: Are there spiritual insights that come from sleep?

PQ: Oh yeah, definitely. I have an archetypal dream where I’m going up a mountain, and I know I’ve been on this mountain before — it’s a familiar mountain, although it looks different every time. The first time I had this dream, it felt really good going up it. I felt close to the Absolute. In the dream, the mountain wasn’t far from the monastery, but nobody knew about it, so I thought, Oh, this will be wonderful, I can lead people up to this mountain now. And that dream has really had a controlling effect in my life, because I often find myself leading people through the woods, up the knobs or ridges. It’s one of my favorite habits.

M: In one of your poems you ask this profound question: “Is death […] depth of freedom / unconfined by place and time — / a boundless treasure of all for all / wherein nothing is mine?” I was wondering, could the same be asked of sleep? Is sleep a “depth of freedom”?

PQ: Partially it is. I think that’s what dream activity is. Your mind is free to recreate reality. You know, reality imposes itself on us, it’s always coming at us and it’s got its definite form and has rules of its own. Well, the mind gets tired of that, and so in dreams it breaks all the rules and makes its own reality.

I suppose drugs do the same thing too. I’ve never been into drugs though.

M: I know you meditate outdoors for 30 minutes or so twice a day. In your book you talk about how you also love to sleep outside — you call yourself a “nighttime hermit who sleeps like a yard dog outside all year long.” I liked that line. Why do you like to meditate and sleep outside?

PQ: Well, nature is very congenial with meditation; I think, in a way, it softens the effort. Of course, there’s always something going on, but there’s a kind of kinship or connaturality between meditation and being outdoors. And then as far as sleeping goes, I think it’s just a way of getting more solitude. There’s something about waking up in the middle of the night when there’s nobody nearby, you’re just totally alone, that gives you a deep experience of solitude.

M: You’ve also written about a period in your life when you were constantly being harassed in the night by a very stubborn mockingbird. Do you still have disruptions to your sleep from birds or other animals?

PQ: For the most part, no. And it’s not too obnoxious when I do. I mean, the other night, while I was trying to sleep, I heard this chomp, chomp, chomp sound. Instead of getting up, I just clapped my hands and yelled, and it stopped for a minute or two. But then I heard it again: chomp, chomp, chomp. So I stood up and there was a groundhog chewing on a piece of lumber. When he saw me and I yelled at him — I said, you keep quiet over there, and pointed right at him — he and his wife turned around and left.

I think groundhogs are probably like beavers — they need to grind their teeth down a bit because their teeth will get too long if they don’t chew on something. Or maybe he just enjoys chewing things.

M: What do you do when you can’t sleep at night?

PQ: For me, it’s usually just that I wake up early. I’ll say Psalms, ones that I know by memory, and I’ll just lay there and wait until my alarm goes off. Last week I woke up one morning at 1:15 a.m., and after a while I knew I wasn’t going to get back to sleep, so I just sat up and started praying, you know, going through the Jesus Prayer on my beads.[2] And then of course I had to catch up on sleep later in the day.

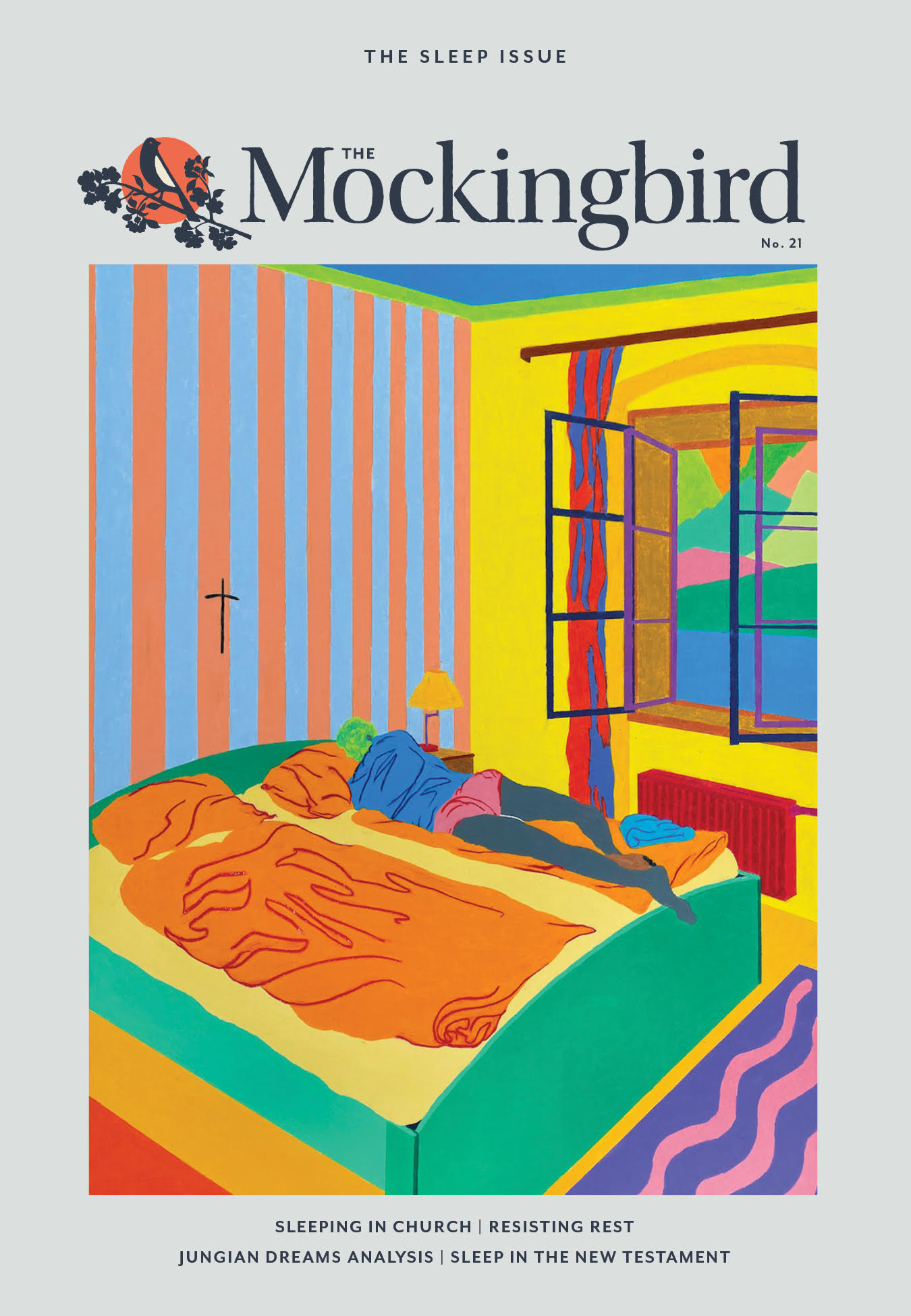

Illustration by Hannah Lock

M: You knew Thomas Merton pretty well, or as you called him, Fr. Louis. I’ve always had this dual impression of Merton as someone who was restless and almost overserious at times, but also had a gregarious, fun-loving side. Is that true?

PQ: Yeah, that’s true. He wrote a lot about his contradictions, and you defined just some of them. But for the most part he was upbeat and witty, and serious. He was always busy, you see. He had a lot of work to do, and he also wanted to get some writing done. And he also suffered from insomnia — he had such an active mind. I don’t know how he handled it, but I guess he just didn’t get much sleep. Some people are like that, you know. We’ve had some guys here, brilliant guys, and they’ll get by with five hours of sleep. Some people get by with even less.

M: Is there a saint you know of that’s associated with sleep disorders or insomnia?

Not that I’ve heard of — we’ll have to make up one.

M: I don’t know if they’ll ever canonize Thomas Merton, but maybe he’ll be the one.

PQ: Oh, no, that would ruin him. Why ruin him by canonizing him? He’s sort of a mentor for the marginal, and if you put him up on a pedestal then that kind of spoils him.

M: I suppose that’s true. Merton, as well as other spiritual masters like St. John the Divine, often spoke about the spiritual life as a kind of journey into holy darkness. Is there any of that imagery that resonates with you?

PQ: Oh yeah, a lot of it. Maybe that’s one reason why I like sleeping outside. I’ve developed a kinship with the darkness. You know, the nights can be very beautiful, and I think I was well-conditioned by Merton because early on I learned what to expect. If you’re not always “in the light” as a monk, that’s part of the procedure. I mean, you don’t get worried about if God has abandoned me or something.

M: There’s a wonderful passage in your book where you talk about your struggle with narcissism as a young man, and some of the interactions you had with Merton around that subject. Merton said that “most young men are narcissistic,” and his general remedy for you was to embrace life as a monk and stop navel-gazing. How could people who are not in the monastery become a little less narcissistic and a little more self-forgetful?

PQ: First of all, you have to recognize it. Because our culture actually encourages narcissism. People think that’s the way they ought to be. They’ll gravitate towards narcissistic superstars, politicians, and so on, and they think that’s the norm. Of course, narcissism takes different forms. It’s not a one-face syndrome; it’s got many faces. I guess you could try to get a wise mentor who can see what your problem is and maybe help steer you away from it.

M: One of the phrases you’ve used to describe the monastic way of life — and you were quoting St. Benedict — is a “labor of obedience.” Obedience is a word I struggle with. What does obedience look and feel like for you on a daily basis?

PQ: Well, I follow the monastic schedule. I’m there in choir when it’s time. I do what’s been assigned to me to do — working in the kitchen, cleaning the jakes [a.k.a. latrines] when my time comes around, all that. But that’s kind of routine. There are lots of other ways that I kind of give myself slack. You know, there’s always house rules about things, and they’re mostly based on the Rule of St. Benedict, but to what extent do I take seriously all the house rules? For instance, I’ve got some friends visiting this week. Do I have to ask the Abbot permission to go visit them? Well, my practice is no. I just kind of go along with what the opportunity offers. So I’m not a model monk. But I think that’s probably the way it is with most of the guys.

It really has to be a moment-to-moment thing, because God offers opportunities. I mean, what the heck, here I am talking to you on the phone, and I’m supposed to be a sequestered monk! Although the fact is, I’m also in charge of the Abbey’s media contact, so in a way it’s my job. But the Abbot also says he doesn’t like interviews. I forgot to even take that into consideration when I agreed that we could have this interview.

M: Haha. Well, I certainly appreciate it. I mean, to me, it sounds like you’re talking about grace.

PQ: Yeah, definitely. I wouldn’t even be living if it wasn’t for grace. I mean, the only miracle I know is that I’m still here.

Paul Quenon: Br. Paul Quenon, O.C.S.O., entered the Trappist Abbey of Gethsemani in Kentucky in 1958 at the age of seventeen, where Thomas Merton was his novice master and spiritual director. Br. Paul is the author of the award-winning book In Praise of the Useless Life: A Monk’s Memoir, as well as nine collections of poetry. He sleeps under the stars each night and is an avid hiker and hill climber.

COMMENTS

Leave a Reply