I have prayed to precisely one saint in my life — and it was an accident. I was on retreat at a convent in preparation for my ordination some years ago, and joined the nuns there for evening prayer. I don’t really understand Latin, but I’m a team player, so I sang along with their Latin hymns and added my voice to their prayers. Next to me, a few other ordinands snickered. “What’s wrong?” I whispered. “You just asked St. Walburga to pray for you” they whisper-laughed. Time to turn in my protestant card, I guess.

A popular image of St. Javelin, by Chris Shaw

While St. Walburga isn’t the most popular patron, there is a much flashier saint making the rounds today. Her name is St. Javelin. Never heard of St. Javelin? She’s more of a meme than a real saint, a creation of our anxieties surrounding the war in Ukraine. This street-art icon features the Blessed Virgin Mary holding the famed Javelin anti-tank missile launcher across her chest, and her blue halo features a pair of golden Ukrainian tridents to get the point across.

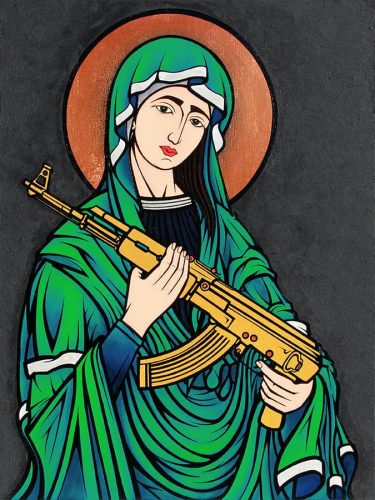

You can also find St. Mary of Kalashnikov holding an AK-47 and other knockoffs of “The BVM” holding grenades and rifles. You can get the images on bumper stickers, t-shirts, flags, tote bags, and fake icons, with the profits going to Ukrainian relief efforts. It’s a very odd mix of religion, memes, war, and commercialism.

It’s a potent mix too. There’s a part of me that would love to pray to St. Javelin, to order stickers for my laptop and hang her flag on my front porch. Wouldn’t we all love to believe that the holy warriors of God were serving on the front lines in the Donbas, fighting off the tyranny of Vladimir Putin? How fun and exciting it is to imagine St. George, famous slayer of dragons, and St. Michael, fierce archangel of God, fighting the Russians and the forces of spiritual darkness alongside the virtuous underdogs of Ukraine.

It’s an intoxicating spiritual cocktail to think that these saints would take up arms in the cause of the earthly good. Imagining St. Mary with a rocket launcher is cheeky and transgressive and scratches an inner itch for justice that exists in every human being.

I wish! I wish I could believe all this to be true. I wish I could pray to St. Javelin during this season. But I can’t. I can’t pray to St. Javelin because of what Jesus did in Holy Week.

The night before his crucifixion, we find Jesus himself telling his disciples to put down their weapons. It’s not a suggestion — it’s an urgent command. A posse has come to arrest Jesus, and Peter has already lunged forward to attack with a sword, preemptively striking one of the men and cutting off his ear. St. Peter is doing his best impersonation of St. Javelin. But as soon as the violence begins to break out, Jesus shuts it down. He heals the detached ear, and lets himself be chained up and led away instead. There would be no violence in Gethsemane.

And the next day, Jesus allows the Romans to crucify him, putting up no resistance other than a sure and certain confidence in God’s providence. He is like a sheep being led to the slaughter: unresisting. St. Javelin may have taken up arms, but Christ allowed his arms and side to be pierced. It was all part of the plan, of course, but most of us do not plan for our own defeat like Jesus does.

Good Friday inverts our expectations about where to find Jesus Christ or any other saint in Ukraine’s war. I do not think we would find him piloting drones or hoofing Javelins, or even taking smartphone videos of war crimes to share with the world. Instead, I think Jesus was probably sitting next to a terrified Russian reservist, who has realized too late that he is not a rescuer, but an occupier, whose tank was moments away from being blown up. Or if he’s not there, Jesus was probably waiting in line at the train station in Kramatorsk that was bombed last week, killed alongside the other 50 civilians when the missile fell unannounced from the sky. Or if he’s not there, Jesus was tied at the wrists and ankles and executed in Bucha, and his body is probably still unburied and lying on the street. Or maybe Jesus was one of the unborn children who died in the womb with his mother when a missile struck the Woman’s Hospital in Mariupol.

St. Mary Kalashnikov by Chris Shaw

In this time of wild geopolitical upheaval, praying to St. Javelin can take a lot of forms. I know fellow Christians who are praying for Vladimir Putin’s assassination, and I know of others yet still who are praying for World War III so that the end times will come sooner and trigger Jesus’s return. Others share memes of The Sunflower Curse and praise The Ghost of Kyiv, while joking that Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky is a 2022 sex symbol. As for me, I find myself staying up till 2am on Twitter and Reddit trying desperately to find any updates I can as I root for the Ukrainian people like the good guys in some months-long action movie. Perhaps I have accidentally prayed to two saints instead of just the one.

One popular piece of advice going around nowadays is to channel our rage into the imprecatory psalms, and pray along with the scriptures that are curses for Israel’s enemies. Across a number of psalms, King David and other writers pray that their enemies would have their teeth knocked in and die and go to hell, or that they would shrivel up like salted snails, or that their babies would die horrific deaths. I am grateful that King David’s rage was public and preserved in scripture. Our own rage is reflected back to us in people God used in earlier times, proving that such anger is not an impediment to a relationship with heaven.

In light of Good Friday, however, I still think such imprecatory prayers, even if they are prayed in Jesus’s name, are actually prayers to St. Javelin. The crucified Christ does not quote the imprecatory psalms on the cross, opting instead for words of forgiveness and mercy. In fact, the one psalm he does quote is a psalm of trusting God in the midst of total defeat. The analogies to salted snails and condemnations to hell are not found on Golgotha, except, perhaps, in the body of the King himself. Lord knows some of Jesus’ opponents had been praying imprecatory prayers at Jesus across the weeks and years prior.

If the cross is God’s response to the injustices of the world, our whole notion of where we expect to find God must be recalculated. Certainly we think God is involved in the great blessings and breakthroughs of our lives. But do we think to look for God in the hardships and tragedies too? Good Friday inverts our expectations about where to find Jesus. If we expect to only find God’s fingerprints in the wins of our life, it is likely we are praying to St. Javelin instead of embracing the way of the cross.

Is it possible to find God in the midst of our fights with our angry teenagers, or in our failure to secure a raise at our job? Do we dare look for grace when our kid is diagnosed with an eating disorder, or when a freak car accident breaks our bodies and gives us chronic pain? How could the goodness of God be made evident in our miscarriages, our estrangements, or our addictions? If Good Friday is all that Jesus intends it to be, then even the greatest failures and tragedies of our lives are not beyond the redemption of heaven.

We pray to St. Javelin because defeat is terrifying. We have forgotten the hard lessons of Good Friday, the unpopular ones about loving enemies and getting smacked in the face voluntarily and repeatedly. Find me the Christian who is praying for Vladimir Putin to repent of his sins and find new life in the gospel while giving to humanitarian relief efforts. Find me the believer who is praying “father, forgive them, for they know not what they do” for the Russian conscripts who unknowingly became cannon fodder. Find me a faithful person praying for Jesus’s return before a third world war begins. There you will find the grace of heaven working at its fullest.

Maybe this is all too pacifist. Perhaps I am wrong, and God is calling me to take up arms in the cause of justice. If so, I will pray to him for forgiveness for my cowardice. And maybe St. Walburga will intercede for me. But if Jesus’s words are right, then those who live by St. Javelin will die by St. Javelin, and the saints who will truly find God’s favor are the poor, the mourning and the peacemakers. Sadly, those saints make terrible memes, but they will certainly make for a glorious heaven.

COMMENTS

4 responses to “Why I Can’t Pray to St. Javelin”

Leave a Reply

Excellent piece. FWIW – I am Chris Shaw, the original creator of the art, it’s not Victor Bonaccius. http://www.chrisshawstudio.com

Chris! Thank you so much for the kind words and the correction. Please see that we’ve updated the attributions in the post accordingly, our sincere apologies for getting that wrong. So glad you appreciated the reflection on faith and war. Those icons are so damn compelling, they’ve even got the theologians thinking. Thanks again reaching out to us – it means the world!

Hi Bryan, thanks for the thoughtful and timely piece. Were you up at the Abbey of St. Walburga in Colorado? I’m an oblate (and a Protestant, still) with them and have been to their Compline service where they sing their hymn to St. Walburga. It’s beautiful – I don’t blame you for singing along!

This was at St. Emmas in Greensburg PA, outside of Pittsburgh. They have a shrine to St. Walburga on their campus. I don’t know how many hymns there are invoking St. Walburga, but this one was beautiful too. It’s on my list of places to return to for a retreat in the near future.