This article is by Joe Duke:

I knew Flannery O’Connor. She lived in Milledgeville, Georgia and so did I. She was friends with my parents and by proxy, friends with me — as much as a young child can be friends with an adult. Those who knew her in our small town knew her as Flannery.

Sometimes we would visit Flannery at her house, the Andalusia Farm, often on Sunday afternoons. Dad called her before we showed up because that was proper. Arriving unannounced might violate the respectable rules of southern etiquette.

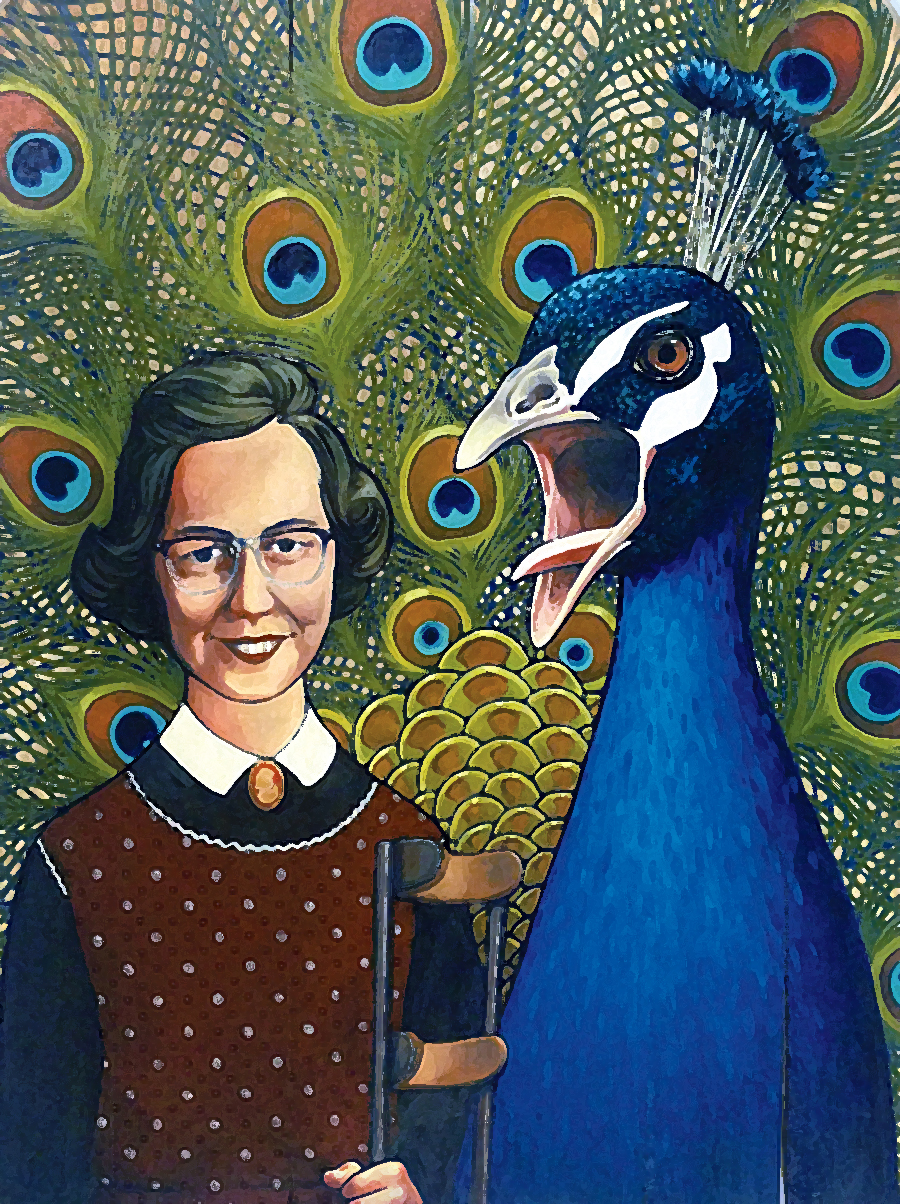

As a six-year-old, I thought of Flannery as the lady with the peacocks and crutches. She had so many peacocks or peafowl as they’re also called. Truthfully, those birds were the main attraction during my childhood visits to Andalusia. The peacocks were almost magical with their enormous, colorful tailfeathers.

But I was also curious about Flannery’s crutches. They were the kind that wrapped around her upper arms. And I couldn’t stop looking at those crutches. I wanted to know more. One time, I asked her the awkward question, as children are prone to do: “Why do you have those?” Maybe sensing my parents’ uneasiness, Flannery quickly replied, “They help me walk.”

As I grew older, I learned much more about Flannery O’Connor. She suffered from Lupus, an autoimmune disease that creates pain throughout the body and stiffness in the joints. In the final stages it attacks major organs. Eventually the disease would claim Flannery’s life as it had her father’s. She would die at 39. Those crutches allowed her some mobility even while her Lupus got progressively worse. In her later years, her bed was moved into the living room on the main floor with her working space and typewriter only a few feet away. I remember not being allowed to go in that room or go upstairs.

As I grew older, I learned much more about Flannery O’Connor. She suffered from Lupus, an autoimmune disease that creates pain throughout the body and stiffness in the joints. In the final stages it attacks major organs. Eventually the disease would claim Flannery’s life as it had her father’s. She would die at 39. Those crutches allowed her some mobility even while her Lupus got progressively worse. In her later years, her bed was moved into the living room on the main floor with her working space and typewriter only a few feet away. I remember not being allowed to go in that room or go upstairs.

Flannery O’Connor was a Roman Catholic and a devoted one at that. As good Methodists, our family didn’t know much about Catholics, only that they were different from us. The Catholic Church in town, where Flannery attended, seemed marginally mysterious to me as a kid. Whenever we passed that church and I wondered about it out loud, my questions were met with short and evasive answers from my parents. Those responses were like the reaction of an intolerant policeman working a fender bender at the intersection of Hancock and Jefferson. “Move along now. Nothing to see here.” I always wondered what went on inside that church, behind those doors.

If the Catholic Church seemed mysterious, so did Flannery. I learned that many viewed Flannery as eccentric and her writings as macabre. Her writing style was Southern Gothic which sometimes featured stories of the grotesque or delusional. Her approach was shared by other writers like Walker Piercy, Eudora Welty, Harper Lee, and William Faulkner. Flannery wrote, “I have found, in short, from reading my own writing, that my subject in fiction is the action of grace in territory largely held by the devil.”[1] Seems to me, that’s essentially what God is up to all around us — grace making headway in a lost and broken world. Her appalling ending to her short story, A Good Man Is Hard to Find,[2] left me convinced of the devil’s territory but still looking for more grace, at least in that story.

Flannery was controversial, but she was also insightful and profound. She wasn’t afraid to push through the boundaries of appropriateness. She often exposed stereotypes and confronted the status quo with an in-your-face realism. Listen to her honest perspective — an indictment of our tendency to partition off the spiritual from our real lives:

It is when the individual’s faith is weak, not when it is strong, that he will be afraid of an honest fictional representation of life; and when there is a tendency to compartmentalize the spiritual and make it resident in a certain type of life only, the supernatural is apt gradually to be lost.[3]

Of course, that’s true. Flannery is saying what others have also understood: the division of the secular and sacred is artificial. The work of God and our daily pursuits are all rolled into one experience called life. And it’s all spiritual.

As a southerner, Flannery lost little love on northerners. “Yankees,” she called them. But she was also adept at honest critiques of those in the south. In commenting on the grotesque in southern fiction, Flannery asserts that, “… Southern writers particularly have a penchant for writing about freaks…because we are still able to recognize one.”[4]

In reading Flannery, I’m usually backhanded by her words — slapped off balance by the piercing truths cloaked in her wisdom and wit. She’s funny and profound at the same time when she observes that the south is hardly Christ-centered but is most certainly Christ-haunted.[5]

It’s clear Flannery wrote what she really thought but did it so masterfully. And she was undeterred by criticism and scarcely concerned with image management as we know it today. Flannery was self-aware and comfortable with her own intelligence and humor. “I don’t deserve any credit for turning the other cheek,” she said, “as my tongue is always in it.”[6]

As a child, I had no way of comprehending who this person really was — this person who was close enough for me to reach out and touch. And I don’t think many of the locals realized the true genius of the woman living just up the road in the Andalusia Farmhouse. Her name was Flannery.

As an adult, I had lunch with a man I had recently met. Somewhere in our conversation he mentioned Flannery O’Connor. I made the casual comment that I visited Flannery often when I was a boy. The man lunged forward astounded, almost falling face-first into his Cobb salad. You would have thought I was saying I’d been to Mars and back. Then it hit me; Flannery was then and is today somebody extraordinary. Maybe because I knew her, I was late embracing her notoriety. She is a prominent author in American literature;[7] and her works are experiencing a resurgence of influence and popularity. All over the world, people are discovering Flannery O’Connor.

In 2015 the U.S. Postal Service issued a “Forever” stamp honoring Flannery. And many years before that, she was publishing books and short stories and giving lectures and winning awards. Flannery died young in 1964. People often refer to her death as untimely. Maybe. But she crammed so much life into such a brief span. Like her writing, her life was a short story but rich in meaning.

My appreciation for Flannery has grown exponentially over the years. Sometimes I wish I could return to those days when I was in her presence. What would I say? What could I learn? But those days have passed.

I recently visited her home and walked her property again. It’s now a museum. So many memories came flooding back. The peacocks, still there. The sitting room where we would visit with her. Her simple kitchen. The water tower. Her crutches now leaning against her desk. But her biggest legacy? Her written works — still alive and offering an invitation for all to come and visit with Flannery.

Joe Duke is the Founder and Executive Director of GraceWorks International and the Co-founder and Pastor Emeritus of LifePoint Church where he served as Pastor for over 35 years. Joe is a graduate of Asbury College (University) and Dallas Seminary (ThM). He is a writer and speaker who is obsessed with helping people grow in the grace and knowledge of Jesus. Joe’s book, Reflections: Words to Inspire, Challenge, and Encourage You is available on Amazon.

COMMENTS

One response to “The Lady with the Peacocks and Crutches”

Leave a Reply

I have a list of writers I thank God for every day. Here goes (dead first): Chesterton, George MacDonald, C S Lewis, Tolkien, Sayers, Charles Williams, Dostoyevsky Tolstoy, Solzhenitsyn, Levertov, Flannery O’Connor, Walker Percy, Raymond Carver (living next ): Niall Williams, Fleming Rutledge, and Wendell Berry. Check out Raymond Carver’s poems “ What the Doctor Said,””Gravy?” And “Late Fragment” and his short story,” A Small, Good Thing.” My favorite Flannery story is “Revelation.”