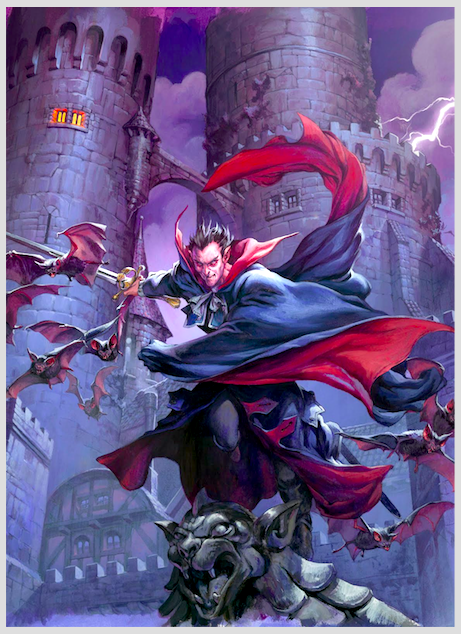

Another year, another Dungeons and Dragons campaign on the books. Fully enveloped within the modern resurgence of the classic fantasy roleplaying game, I’ve been running (“dungeon mastering”) a series of campaigns for my wife and our group of best friends over the past few years. We just wrapped up a six-month campaign where our party of intrepid adventurers vanquished the menacing vampire Strahd von Zarovich, lord of the cursed land of Barovia.

The party attained victory despite their best efforts to derail the campaign, which have at various times included stuffing scrambled eggs in the books of an insidious aristocrat, trying to jump on Strahd and ride him like a steed, flirting with pretty much every non-player character in the game, and intentionally spilling beans everywhere. I mean everywhere. As icing on the cake, our heroes allowed a famous vampire hunter (in the vein of Professor Van Helsing from Bram Stoker’s Dracula) to be summarily executed without doing anything at all to stop it, and failed to prevent an entire town from burning to ash. That was a fun plot-hole to try to dig them out of. Phew.

After several misadventures, and against all odds, the party’s human bard/barbarian Terry Crews (my little brother) reached Strahd’s tomb, hidden deep beneath Castle Ravenloft, and slammed his magical Sunsword into the heart of the arch-villain, breaking the curse over the land of Barovia once and for all. Victory! Ah, a happy ending. The clouds have lifted, and a new day dawns. All is right in the world.

At least, I think that’s got to be true. Strahd is the blight upon Barovia, and his destruction at the hands of the adventurers is the “happy ending” to the tale. Right?

Having lived behind the dungeon master’s screen for six months, obsessively reading and re-reading the campaign book and digesting everything about the big bad evil guy of the adventure, I’m honestly not sure that its vampiric hunt provides either me or my players with the clean-cut happy ending we think we deserve. Well — at the very least, that’s true for me. I think my players were just happy stuffing eggs in people’s pockets, but such is life.

The character of Strahd von Zarovich originally appeared in the Advanced Dungeons and Dragons module Ravenloft, which was published in 1983. Strahd seems heavily drawn from two primary sources: Bram Stoker’s archetypal Dracula, and the short story “Vampyre,” published in 1819 by Lord Byron’s physician Polidori and based heavily on Byron himself. These early vampire stories appear to be the source of our common understanding that vampires are fundamentally and irrevocably evil (which of course clashes with more recent retellings of the vampiric myth, à la Stephenie Meyer’s gold-standard Twilight saga and the mass-market teen vampire sub-genre it spawned).

Tracy Hickman, who along with his wife Laura is the original creator of the Ravenloft module and its vampiric villain, writes about the influence that the historical Lord Byron holds over the construction of the early “romantic” vampire in literature:

For Laura and me, [the decadent and predatory characteristics of Lord Byron] were the elements that truly defined Strahd von Zarovich — a selfish beast forever lurking behind a mask of tragic romance, the illusion of redemption that was ever only camouflage for his prey. (4)

Similarly, in Stoker’s tale, Dracula uses his vast riches, lifetimes of accumulated military expertise and intelligence, and supernatural powers to bend others to his will, feasting on their blood and transforming them into his thralls. In no way is Dracula a good guy. Stoker is completely unambiguous about the darkness brooding within the Count.

In these early romantic vampire tales, the near-human and sympathetic characteristics of the vampire are a complete sham, a lure applied to unwitting humans as bait for the vampiric trap. The core of the classical vampire upon which Strahd von Zarovich is based is cruel, inhuman, and subject to the base animalistic tendencies of the hunter seeking its prey. There is nothing redemptive in the primary thread of the vampiric myth.

And yet, if we dig beneath his layers of false romanticism and vile darkness, Strahd von Zarovich maintains the morally grey whisper of a still-deeper core of ontological brokenness. In order to prepare the dungeon master for the campaign, the Curse of Strahd module describes the events which brought Strahd to his lordship over the lands of Barovia and led to his transformation into a vampire. Strahd, having murdered his brother Sergei out of jealousy for Sergei’s fiancee,

saw the faces of his father and mother in the thunderclouds, looking down upon him and judging him. He had destroyed the family bloodline and doomed all of Barovia. The castle and the valley were spirited away, locked in a demiplane surrounded on all sides by deadly fog. For Strahd and his people, there would be no escape. (9)

As much as Strahd is driven by the base tendencies of the vampire, there are clues throughout the campaign that he is also driven by self-hatred for the doom he brought upon his family and his people through his greed. In the final encounter with Strahd, deep beneath the stones of the vampire’s castle, the adventurers don’t find him sucking the blood of some hapless commoner, or whispering foul incantations in a dark crypt. They stumble upon him weeping over the tomb of his brother, wrapped up in grief over the pain and suffering he created.

When Terry Crews finally killed the vampire lord, the module instructed me to read,

Surprise turns to rage, and the Pillarstone of Ravenloft trembles with fury, shaking the dust from the ceiling of the vampire’s tomb. The shudders abate as Strahd’s burning hatred melts away, replaced at last with relief… (207)

Similarly, if we examine Bram Stoker’s Dracula at greater length, underneath the blatant overtones of moral black and white and good vs. evil, there are subtle strokes of sadness and regret. The protagonists take time to reflect on the tragedy of what Dracula has become, and acknowledge that beneath the layers of darkness there is (or at least was) a human being. Mina Harker, who is the character most vulnerable to contracting vampirism for most of the novel, states,

That poor soul who has wrought all this misery is the saddest case of all. Just think what will be his joy when he too is destroyed in his worser part that his better part may have spiritual immortality. You must be pitiful to him too, though it may not hold your hands from his destruction. (327)

Within the classical vampiric story, the romantically tragic “near-goodness” of the vampire speaks in two voices: primarily, it is a finely tuned ruse used to entrap human prey. This is the reading we all have internalized about the vampiric myth — the vampire is at its most dangerous when it is a sympathetic character. At the same time, a still small voice acknowledges that the tragedy and the pain of the vampire is undeniably real. The vampire was, at one point, a human like the heroes of the story.

In both Bram Stoker’s tale and our campaign, the vampire is both antagonist and victim. Simultaneously vicious and broken, seemingly invincible and neurotically aware of its own weaknesses, the classical vampire is primarily corrupted beyond repair and utterly evil. Simultaneously, the tragic shadow of what was, or what could have been, is subtly woven into the mythos. This conflicting duality dooms the vampire to parasitically leech the lifeblood it subconsciously knows it should be able to attain itself but cannot. The eternal lust for blood is a symptom of a more fundamental loss of humanity which the vampire constantly experiences, regardless of whether it consciously acknowledges or understands its need.

And in a perplexing way, the sliver of humanity within the vampire mixes the moral black-and-whiteness of vampire hunting into giant gobs of grey mess. For Van Helsing and his crew, and for my group of heroic adventurers, a quandary becomes readily apparent: how much of their vampiric hunt is defined by their own need for prey? Would my players have been heroes should they have been unable to kill Strahd, and, in their own way, draw the blood of the ‘other’?

The ‘good guys’ in these stories are forced to compare their own humanity against that which is ‘sub-human’ and in doing so seal the doom of the vampire. And yet, both the vampire and the non-vampire are killers. They are both killers in the literal sense of ‘driving the stake through the heart of evil,’ and ‘sucking the blood of the innocent,’ but also in small ways, or in the words of the Book of Common Prayer, “by what [they] have done, and by what [they] have left undone.” What both groups “have done” is concrete physical violence; what they “have left undone” is equally condemning. Neither the villain nor the heroes are innocent.

The paradox of the vampire is universally applicable to all of us: because a glimmer of past humanity remains, the vampire is driven to suck the blood it knows it should already possess. It thinks in terms of “prey” and “non-prey,” living in a constant zero-sum game where humanity is a scarce resource that must be defined by taking it from those it deems as ‘lesser.’

The paradox of the vampire is universally applicable to all of us: because a glimmer of past humanity remains, the vampire is driven to suck the blood it knows it should already possess. It thinks in terms of “prey” and “non-prey,” living in a constant zero-sum game where humanity is a scarce resource that must be defined by taking it from those it deems as ‘lesser.’

By definition, the heroes are required to act in essentially the same way. They wouldn’t be heroes if they did anything different.

The protagonists in Dracula condemn a woman who succumbs to vampirism to damnation for the “sin” of contracting the curse at the hand of the Count. My Dungeons and Dragons group let their vampire-hunting ally die and a village burn to the ground in their comically inept hunt for Strahd. We all “suck the blood” of the other, trying to validate our own humanity by condemning the alien and the inferior. We think that our bloodsucking habits will provide us with the sustenance and lifeforce we so desperately crave, but it is ultimately a farce and a sham; our hunger remains unsated and the desire for new victims is never quenched. In this way, the unequivocal evil of the vampire, the curse of Strahd, which remains an absolute and non-relativized evil, is also a condemnation levelled upon us, the ‘real humans,’ because we ourselves act like vampires every single day. The shadow of the vampire hangs over all of us, it seems. The thirst for blood is universal.

Catholic theologian James Alison provides insightful commentary on the role that communal scapegoating plays in the story of the Gerasene Demoniac from the Gospel of Mark. The account is one of my favorite stories from the Gospels. In the country of the Gerasenes, easily read as a biblical Barovia or Dracula’s Transylvania, there is a demon-possessed man who has been dwelling “Night and day among the tombs and the mountains…always howling and bruising himself with stones” (Mark 5:5). What an eerie and haunting sentence. Like a vampire, alive but living among the dead, this man who has been outcasted from his community appears to have turned on the only prey available to him: himself. Jesus, taking part in an entirely unorthodox and paradigm-flipping “vampire hunt,” lands on the shoreline and steps out of his boat. Alison picks up the narration of the story:

The man, or the spirit, recognizes Jesus from afar. He runs and worships him, and adjures him by God not to torture him, for Jesus has told the spirit to leave him. Jesus asks the spirit to name itself, and it names itself Legion ‘for we are many.’ It begs not to be sent out of the country. Not surprising, for Legion is entirely part of the economy of that place: it is the interrelationship of compulsions and driving forces that keep that people together by enabling them to agree on having someone who represents what is not them, all that is dangerous, unsavoury, and evil. (125)

In our campaign, Strahd is the Gerasene Demoniac. He is the scapegoat that allows the heroes to avoid confrontation with the ways in which they all act like Barovian villains, looking out over their lands from their spooky perch in Ravenloft castle. He represents what is absolutely different and distinct from them, and therefore damnable, regardless of the snapshot of humanity that remains within him.

Alison continues:

Yet this is not the logic of the Gospel. In the logic of the Gospel, the language of demonic and of exorcism has a quite different function: it points to the Creator peacefully calling to life those whose being has been trapped by the violence of cultural belonging…this is the real dynamic behind the story of the Gerasene demoniac. It is the story of what it looks like when the living God, the utterly vivacious Creator out of nothing, draws near to the ersatz god of group being and belonging, and by taking the weakest member of the group, begins to collapse the group’s belonging, humanising the ‘bad guy’ and thus initiating the possibility of a quite different sort of social formation. (130-131)

The Gospel speaks powerfully into this universal economy of “us vs. them,” of “vampires vs. humans,” by acknowledging that the fundamental conditions which drive vampiric myths are universally experienced by all of humankind — vampire and hero alike. Thus, when Jesus humanizes the “bad guy” in the story of the Gerasene Demoniac, he also humanizes the community which made the Demoniac the villain in the first place. In encountering the person of Jesus, both the Demoniac and the villagers realize the commonalities between them — that both have a desperate need for blood which they cannot attain on their own.

Similarly, the truth is that both Strahd and the heroes who sat around our game table every week live in a state of brokenness. The distinctions between our halfling thief, dwarf paladin, elf assassin, and the vampire lord himself are smaller than we might think. All are blood-suckers who can’t save themselves. All are in need of grace.

Thus, the Curse of Strahd module, rewritten according to the Gospel edition of DnD, would involve Jesus calling both Strahd and the adventuring party out to some lonely hilltop. He would fully acknowledge that all of them are vampires — all of them are guilty of bloodsucking. And then he would show them the scars of his crucifixion in acknowledgement that the zero-sum game of the vampiric predator-prey relationship has been broken. Jesus’ own blood has entered the economy of the vampire and broken it completely. The blood that both the heroes and the vampire so desperately need has been shed for them already. There’s no more need for bloodsucking.

And that would be that. No rolling for initiative. No skill-checks with the Sunsword. The game would already be over because everyone — both the party and Strahd, both Van Helsing and Dracula — have been given victory through the true hero who was driven through the heart with a wooden stake for all of us vampires.

COMMENTS

6 responses to “I’m a Vampire! I’m a Vampire! I’m a Vampire!”

Leave a Reply

Fantastic.

Oh bröther this is güd

*successfully jumping on Strahd and riding him like a steed

Great article!