For those of us who attend Lectionary-based churches, last week Mark’s Gospel reminded us of the time when Jesus faced a nasty rejection. He was in Nazareth, among his own, but his own received him not. They dismissed him by pointing to his apparently illegitimate birth, saying, “Is this not Mary’s son…?” (subtle but powerful slander in this patrilineal culture). Matthew and Luke cleaned it up a bit, but Mark tells it this way. The people of Nazareth have heard his words, they have seen his actions, and still they have labeled him a bastard.

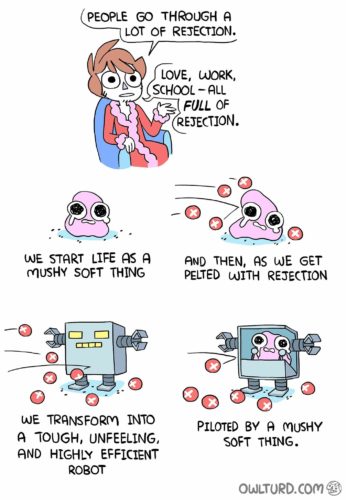

I wonder how we would react to such rejection? Or perhaps, I wonder how we do react to such rejection, because it actually happens to us all the time, whether it’s to our faces or not. And I wonder how our ways of dealing with such rejection square with the way Christ dealt with it. If you or I were rejected in this way, I don’t know about you, but I’d crawl in a hole and hide.

I wonder how we would react to such rejection? Or perhaps, I wonder how we do react to such rejection, because it actually happens to us all the time, whether it’s to our faces or not. And I wonder how our ways of dealing with such rejection square with the way Christ dealt with it. If you or I were rejected in this way, I don’t know about you, but I’d crawl in a hole and hide.

As I said, you and I deal with this kind of rejection all the time, but in order to understand how, I have to back up and talk about a favorite TV show of mine. It was the first science fiction series I ever watched, at the tender age of 9, one that is so rare that most have probably never heard of it. It’s called Space: 1999, and it’s currently available on Amazon Prime.

The show was conceived in 1973, and it looks dated now, but in the most fascinating way, because, having been created in the era of the moon landings, all of the pseudo-technology was actually based off the real technology of the Apollo space program. The premise of the show was that, by 1999, we have a moon base, and we are disposing of the Earth’s nuclear waste on the moon’s dark side because, remember, the whole world was going to switch over to atomic energy. Three Mile Island hadn’t happened yet. And I know it sounds silly, but it had only taken 8 years to go from one man orbiting the earth to another man walking on the moon, so yeah, in another 25 years, why wouldn’t we be living on the moon? That was the thinking behind the show’s premise, and their spaceships, called Eagles(!), were an imaginative cross between the Apollo 11 landing module and a proto space shuttle. If one took the top half of the Eagle lunar module and swung it over to one side as a cockpit, put the engines on the other side, and stretched out the bottom half of the module so that it could carry various payloads, that’s the Eagle spacecraft in Space: 1999.

Of course, just four years later we would watch the real Space Shuttle Enterprise take off from the back of a military 747 to glide and land under its own control. American space exploration would shift from the ever-outward focus of celestial landings to one in which the farthest we would dare to go would really just be a high orbit of the Earth, over and over again. And the direction of technology, the technology that has truly impacted our culture, would shift as well, from that ever-outward focus, of taking us to the moon and beyond, to a focus which would lead us ever-inward, which I think is a big part of how we got ourselves into the mess we are in today. Instead of using technology to explore outward, we use it to explore our inner spaces.

Of course, just four years later we would watch the real Space Shuttle Enterprise take off from the back of a military 747 to glide and land under its own control. American space exploration would shift from the ever-outward focus of celestial landings to one in which the farthest we would dare to go would really just be a high orbit of the Earth, over and over again. And the direction of technology, the technology that has truly impacted our culture, would shift as well, from that ever-outward focus, of taking us to the moon and beyond, to a focus which would lead us ever-inward, which I think is a big part of how we got ourselves into the mess we are in today. Instead of using technology to explore outward, we use it to explore our inner spaces.

In a recent post, I talked about how most of us believe that we are more polarized than ever. We have more technological ways to connect with others, but what we’re actually doing with the technology is making us more disconnected from each other than any generation that has ever walked the planet. The technology allows us to live our lives in echo chambers of self-affirmation. That’s certainly true of our circle of Facebook friends, which is a driving indicator of the company we choose to keep. And when we disagree on Facebook with another person’s perspective or view, technology has provided us with more ways than ever to reject that person’s viewpoint by rejecting the person.

We do something similar to what the people of Nazareth did with Jesus. A friend of mine calls this the “what abouts.” Jesus is saying these astonishing things and working these amazing miracles, but what about his illegitimate birth? What about his vocation as a carpenter, which doesn’t bode well for someone becoming a reputable rabbi, let alone the Messiah, the Son of God. That’s what’s at play in the rejection of Jesus, and if you think we’re not doing that today, just think about the way some of us use FB when someone says something with which we disagree.

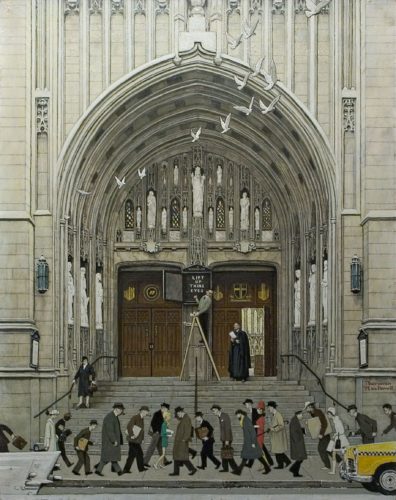

We can now use a person’s profile page as a filter in order to engage in ad hominem dismissals of the person. Someone speaks up supporting something with which we disagree, and we can turn to their profile page, and make so many unfounded assumptions about them, based on extraneous information which is made available to us through the wonders of technology. When we do this, what we’re doing is propping up the echo chamber of self-affirmation in which we live and move and have our being. And the biggest assumption that gets used against us, whether we know it or not, is, “Oh, they’re Christians,” as if that somehow makes us narrow-minded, hypocritical, or things of that nature, whether it’s said to our faces or behind our backs.

We can now use a person’s profile page as a filter in order to engage in ad hominem dismissals of the person. Someone speaks up supporting something with which we disagree, and we can turn to their profile page, and make so many unfounded assumptions about them, based on extraneous information which is made available to us through the wonders of technology. When we do this, what we’re doing is propping up the echo chamber of self-affirmation in which we live and move and have our being. And the biggest assumption that gets used against us, whether we know it or not, is, “Oh, they’re Christians,” as if that somehow makes us narrow-minded, hypocritical, or things of that nature, whether it’s said to our faces or behind our backs.

And when someone else does this to us, it hurts. But then we turn around and do it to others, because what we’re really aiming to do is to stay safe within the echo chamber and to keep any views that might oppose our self-affirmation safely outside. Of course, when we fail at this, it comes off as the ultimate rejection, like what happened to Jesus. And what do we tend to do? We curl up in a ball of self-pity and loathing—perhaps not you, but this is what I tend to do. So, how does that square with Jesus’ reaction to his rejection at the hands of people who should have known him best? In Mark’s Gospel, this is the very catalyst that causes Jesus to begin sending the disciples out, two by two. Instead of drawing in on himself, Jesus aims outward. He broadens the scope of his ministry. In modern parlance, we would say he dials it up.

It’s as if to say, “You want to dismiss me based on something you think you know? I will do even greater things, and I will give some of this same power to my disciples. What will you think then?” But we who are followers of Jesus Christ should look very closely at what he says to his disciples, because he sends them out in complete vulnerability, such that they will be wholly dependent on others for anything they need, and he tells them in advance that there will be rejection. As disciples of Jesus Christ today, if that sounds a little scary to us, it should!

Perhaps that’s the point of the Synoptic accounts of the rejection at Nazareth. If we’re not being rejected as followers of Christ, are we truly following our call? If we’re not bringing people together to reconcile them with Christ, come what may in terms of rejection, are we truly following our Lord, who was himself rejected first? Christ does not send us where he has not already been. And the ultimate rejection is coming. It will come at a time when even his own disciples will fall away. It will come at a time when people will mock him, beat him and shout horrible things, as he hangs blameless on the Cross. How could we as his followers expect that our experience of life in this world should be any different?

Perhaps that’s the point of the Synoptic accounts of the rejection at Nazareth. If we’re not being rejected as followers of Christ, are we truly following our call? If we’re not bringing people together to reconcile them with Christ, come what may in terms of rejection, are we truly following our Lord, who was himself rejected first? Christ does not send us where he has not already been. And the ultimate rejection is coming. It will come at a time when even his own disciples will fall away. It will come at a time when people will mock him, beat him and shout horrible things, as he hangs blameless on the Cross. How could we as his followers expect that our experience of life in this world should be any different?

Of course, this is the exact point at which the good news of grace becomes real, because Christianity is meant to be a life lived at the foot of the Cross, the rejection there actually becoming the ultimate affirmation. On the Cross, God accepted us when we were essentially un-acceptable. God loved us in our unloveliness. All of our efforts at self-acceptance are but pale phantoms when they are compared with God’s love on the Cross.

COMMENTS

Leave a Reply