1. Part and parcel of the juvenilization we touched on earlier this week is the phenomenon UPenn bioethicist Ezekiel Emanuel (best name ever?!) describes as “the American immortal”, that not-so-peculiar species that devotes so much of its time/energy to prolonging life that it kills them (often before they die). Surprise surprise–underneath the aversion to growing up may lurk a denial of human limitation which is ultimately a denial of death. In the latest bit of watercooler bait from The Atlantic, “Why I Hope To Die at 75”, Emanuel challenges the notion of “compression of morbidity”, the widespread presumption that the longer we live, the smaller proportion of our lives will be spent in decline. He presents us with quite a bit of inconvenient data about the reality of life post-75, and makes several policy recommendations. Suffice it to say, “American immortals may live longer than their parents, but they are likely to be more incapacitated.” Never mind that his solutions seem to embrace the same culture of control (and original sin) that fuels the American immortal, or that they equate productivity and vitality/value a little too closely for some of us, the article poses important questions. I was pleasantly surprised by where he took things at the very end:

Americans seem to be obsessed with exercising, doing mental puzzles, consuming various juice and protein concoctions, sticking to strict diets, and popping vitamins and supplements, all in a valiant effort to cheat death and prolong life as long as possible. This has become so pervasive that it now defines a cultural type: what I call the American immortal. I reject this aspiration. I think this manic desperation to endlessly extend life is misguided and potentially destructive. For many reasons, 75 is a pretty good age to aim to stop.

Compression of morbidity is a quintessentially American idea. It tells us exactly what we want to believe: that we will live longer lives and then abruptly die with hardly any aches, pains, or physical deterioration—the morbidity traditionally associated with growing old. It promises a kind of fountain of youth until the ever-receding time of death. It is this dream–or fantasy–that drives the American immortal and has fueled interest and investment in regenerative medicine and replacement organs…

Most people feel there is something vaguely wrong with saying 75 and no more. We are eternally optimistic Americans who chafe at limits, especially limits imposed on our own lives. We are sure we are exceptional.

I also think my view conjures up spiritual and existential reasons for people to scorn and reject it. Many of us have suppressed, actively or passively, thinking about God, heaven and hell, and whether we return to the worms. We are agnostics or atheists, or just don’t think about whether there is a God and why she should care at all about mere mortals. We also avoid constantly thinking about the purpose of our lives and the mark we will leave. Is making money, chasing the dream, all worth it? Indeed, most of us have found a way to live our lives comfortably without acknowledging, much less answering, these big questions on a regular basis. We have gotten into a productive routine that helps us ignore them.

I’m reminded of that truism about the problem with young people rejecting the faith of their parents isn’t that they’ve weighed the claims of Christianity and found them lacking, it’s that they don’t find them worth weighing in the first place. Emanuel’s article suggests that the disinterst may have less to do with post-modernism or intellectual apathy, than a vested interest in ignoring anything that might remind us of our mortality. So perhaps it’s no coincidence that cultures where death is harder to avoid also tend to be more religious. They are less buffered from the truth of existence than those of us who live in a culture designed to distract and defend us from recognizing our finitude. In other words, perhaps faith isn’t so much a crutch against reality as the absence of one.

2. Those looking for the opposite of denial in American culture would do well to read Christopher Beha’s appreciation of Henry James in The New Yorker, specifically how the 19th century literary giant relates to “The Great Y.A. Debate” going on at the moment. Close readers will recall that A.O. Scott mentioned James as an outlier in an American literary canon obsessed with coming-of-age:

James is every bit as concerned with innocence recoiling at adulthood, as Fiedler notes at some length in “Love and Death.”…Why is it, then, that we rightly recognize in James a maturity absent from so much of American culture not just today but a hundred years ago? It is, I think, in part because he treats the passage into adulthood as not just painful or costly but also as necessary, and he looks that necessity straight in the face. What’s more, he treats his reader as a fellow adult aware of this necessity. (In his magnificent story “The Author of Beltraffio,” the narrator asks the famous author whether young people should be allowed to read novels. “Good ones—certainly not!” he answers. Not that good novels are bad for young readers, he adds, “But very bad, I am afraid, for the novel.”)

3. Speaking of The New Yorker, Joshua Rothman is quickly turning into my favorite writer over there. First his piece on the purpose of college, then the elevation of ‘creativity’, and now a remarkable article about “The Church of U2.” For what it’s worth, I agree with him about “Iris”, though my favorite track at this point is probably “Sleep Like a Baby”. Check it:

Even critics and fans who say that they know about U2’s Christianity often underestimate how important it is to the band’s music, and to the U2 phenomenon. The result has been a divide that’s unusual in pop culture. While secular listeners tend to think of U2’s religiosity as preachy window dressing, religious listeners see faith as central to the band’s identity. To some people, Bono’s lyrics are treacly platitudes, verging on nonsense; to others, they’re thoughtful, searching, and profound meditations on faith.

Song lyrics are endlessly interpretable, of course—but, once you accept U2’s religiosity, previously opaque or anodyne songs turn out to be full of ideas and force.

The new album has plenty of good songs, and one great one, “Iris,” about Iris Hewson, Bono’s mother. She died when he was fourteen, after collapsing from an aneurysm at her father’s funeral. Bono compares her love for him, which he still feels, to the light that reaches Earth from a star that’s gone out. It’s a comforting, not unfamiliar idea, until this thought: “The stars are bright, but do they know / The universe is beautiful but cold?” Then the song stops being comforting; it reaches for something it doesn’t quite understand, and possibly doesn’t even want; it becomes ambiguous and mournful. It expresses a particular combination of faith and disquiet, exaltation and desperation, that is too spiritual for rock but too strange for church—classic U2.

4. Despite being scooped by our own Michael Sansbury, The NY Times got a couple of amazing soundbites from XKCD.com jedimaster Randall Munroe for its “We’re All Nerds Now”. The most Mbird-worthy (the excluded becoming the excluders, etc) being:

“People often say, ‘I like your comics, even though I don’t know enough math to get all of them,’ as if it’s some kind of club where they don’t belong,” he said. “But there’s no club. There’s just lots of people who are excited about thinking, learning, joking and sometimes overanalyzing things.”

Mr. Munroe said it was healthy that the tech culture had seeped into the larger culture, and warned against the community turning inward with a “nerd pride or ‘revenge of the nerds’ attitude.” In an email he expanded further: “This can easily become a kind of self-fulfilling prophecy that can make a community steadily more homogeneous and exclusionary.”

5. It reminded me of Meredith Graves’ absolute must-read on the crushing law of indie authenticity. If you can get past the name of her band, you’ll find an essay jam-packed with observations about the impossible standards of artistic purity (read: justification) we foist on our favorite artists, especially the female ones. Her case studies are Lana Del Ray and the ever-fascinating Andrew WK, and while she may blame external factors for the situation more than we might, her words about Robin Williams at the end brought a tear to my eyes:

Women are called upon every day to prove our right to participate in music on the basis of our authenticity — or perceived lack thereof. Our credentials are constantly being checked — you say you like a band you’ve only heard a couple of times? Prepare to answer which guitarist played on a specific record and what year he left the band. But don’t admit you haven’t heard them, either, because they’ll accuse you of only saying you like that genre to look cool. Then they’ll ask you if you’ve ever heard of about five more bands, just to prove that you really know nothing. This happens so often that it feels like dudes meet in secret to work on a regimented series of tests they can use to determine whether or not we deserve to be here.

6. Speaking of Andrew W.K., file this under ‘unexpected’. You may have heard that the party guru has developed a bit of a cult following over the years, as well as a reputation for unconventional, gut-level wisdom (prophetic almost). Which explains, perhaps, why The Village Voice gave him his own advice column. (In fact, if you’re ever looking to kill a few hours, you could do a lot worse than following the fascinating thread of Andrew W.K. fandom to its many odd corners of the Internet a la Ms Graves). Anyway, in a recent installment “Ask Andrew W.K.” a skeptic asked him about prayer, indicating that he considered it to be “superstitious nonsense”. Andrew wrote back an impassioned and even quite moving response, definitely not the sort of thing you find in The Voice very often, a crash course in how to engage someone who fundamentally disagrees with you on spiritual matters. If you catch a wiff of self-improvement, I’d say Andrew’s worth giving the same benefit of the doubt that he gives his penpal. Favorite paragraphs:

Kneeling down and fully comprehending the incomprehensible is the physical act of displaying our respect for everything that isn’t “us.” This type of selfless awareness contains a contradictory aspect that sets the tone for true immaterial experience. It’s the feeling of power in our powerlessness. A feeling of knowing that we don’t know. A feeling of gaining strength by admitting weakness. We work so hard to pump ourselves up and make ourselves believe that we know all the answers and that we have the power and strength to do anything — and we do — but the fullest version of that power comes not from our belief that we have it, but from a humbling realization that we don’t.

The paradoxical nature of this concept is difficult, but it is the key to unlocking the door of spirituality in general, and it remains the single biggest reason many people don’t like the idea of prayer or of spiritual pursuits in general — they feel it’s taking away their own power and it requires a dismantling of the reliable day-to-day life of the material world. In fact, it’s only by taking away the illusion of our own power and replacing it with a greater power — the power that comes from realizing that we don’t have to know everything — that we truly realize our full potential. And this type of power doesn’t require constant and exhausting efforts to hold-up and maintain, nor does it require us to endlessly convince ourselves and everyone else that we’re powerful, that we know what we’re doing, and that we’re in control of everything.

7. In music, there’s THIS, ht DB:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nd_4cSd5IzQ

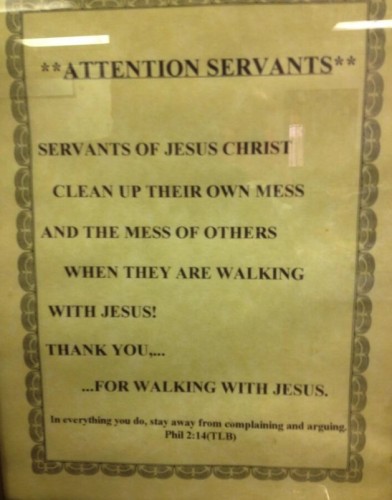

8. Finally, some funny stuff out there this week. First there’s “How To Write an Amazing Passive Aggressive Christian Note”. Then a bolt of youth ministry brilliance hit in the “Lamentations or Taylor Swift lyric?” quiz. It’s harder than you’d think. Next, some genius Disney-fied the Game of Thrones characters. And finally, a couple winners of from The Onion, e.g. “Man Visiting Hometown Amazed To Find All His Childhood Insecurities Still There” as well as “Reclusive Deity Hasn’t Written A New Book In 2,000 Years” which has a few truly memorable quips:

“Certainly in the book business we’ve been wondering for a very long time what He’s been up to, whether or not He’s still writing,” said publishing executive Sandra Eakins, who brushed aside concerns that a lackluster follow-up to the Bible might damage God’s reputation. “Maybe He writes for His own pleasure and has no desire to publish anything new. I can respect that, but at the same time, it’s a tragedy for His readers.”

“We’d absolutely love to see more stories, psalms, epistles—anything He has,” Eakins continued.

“It’s also possible that, with the first book, He simply said everything He had to say,” [critic James] Wood continued.

That last one reminds me of the interview Charlie Rose just did with Whit Stillman, in which Whit praises Salinger:

A Few Strays

– Our friend Nick Lannon would prefer that you quit challenging him (on Facebook).

– Listen Up Philip looks amazing.

– This is a trip: LIBERATE takes over TBN!

– Of course, if you don’t have cable but are looking for your One Way Love fix, our Fall conference in Texas is officially one month away. Be there or be square.

COMMENTS

One response to “Another Week Ends: American Immortals, Henry James, U2charists, Authentic Nerdists, AWK Prays, and Reclusive Deities”

Leave a Reply

Nice work this week!