1. First up, I had the privilege of penning the lead review in the latest issue of Christianity Today on Tara Isabella Burton’s phenomenal new book Strange Rites: New Religions for a Godless World. While the title might suggest significant overlap with #seculosity, Strange Rites is very much its own thing, both in terms of the material covered (wellness! witches! kink!) and the journalistic approach taken. The overall effect is bracing — painfully so in a couple places — but I wouldn’t hesitate to call it essential reading for anyone interested in our rapidly shifting yet eerily static small-r religious landscape.

I had no idea, for instance, that there were more practicing witches in the US at present than Jehovah’s Witnesses. One of my favorite throwaways comes when Burton comments, “While the worries of religious leaders that Harry Potter would inspire a generation of children to practice witchcraft were, certainly, overblown, it’s nonetheless true that many contemporary practitioners of magic trace their interest in it to their childhood reading [of those books].” Wild.

Anyways, you can read the whole thing on the CT site, but here are a few amended paragraphs from the conclusion:

Finally, Burton transitions into the heart of her analysis, profiling three movements vying to become America’s new civil religion: social justice culture, Silicon Valley techno-utopianism, and alt-right atavism. Burton brings admirable empathy to these movements without glossing over their liabilities and clear antagonisms toward her own Christian faith.

Each contender offers a totalizing — and in many cases intoxicating — narrative of the world, our place in it, and the wicked forces that need to be rooted out. Radical social justice movements build their cosmology entirely upon “nurture”: the tabula rasa of humanity corrupted by the original sin of Western patriarchy embodied most fully in Donald Trump. By contrast, the alt-right leans exclusively on “nature,” declaring that the original sins of political correctness and feminism have obscured certain uncomfortable, biologically grounded realities. And although it claims fewer actual adherents, techno-utopianism — with its promise of bio- and cyber-hacking our way to eternal life — boasts by far the most cash. Not inconsequentially, it also controls the platforms (and devices!) on which its two rivals wage their battles.

So where does this leave Christians? First, as Burton takes great pains to note, we dare not hold ourselves above the Remixed. Often enough, professing Christians assent to similar doctrines, both consciously and subconsciously …

If Burton is right, then the old story of the gospel has not lost a shred of potency. To a culture inclined to locate sin and evil out there, we can speak the unifying word of Eden: that “the line separating good and evil,” as Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn famously phrased it, runs “right through every human heart.” That those who cannot live up to their own ideals still have worth and value.

We might present a faith born of love rather than rage, of sacrifice rather than conflict — one that is not put off by human frailty but perfected in it. We might speak of a God who liberates us from the shackles of self and the never-ending mandate of perfection. We might speak of the Holy Spirit, active and alive in the world, bringing goodness, light, and healing far beyond our capacity or imagination.

Most of all, we might offer the one thing that all these new religions conspicuously lack: an ethic of forgiveness and reconciliation, which is to say, the miracle of God’s grace. In Jesus of Nazareth, we have a way forward for victims and victimizers alike. The Prince of Peace does not turn away the guilty, hypocritical, or addicted. Instead, he brings hope and new life to those whose self-made religions can only leave them defeated.

2. Speaking of new religions, the cult of QAnon is being profiled all over the place, from Vice and the Atlantic to Relevant and the Gospel Coalition. Christians, it would appear, are proving particularly susceptible to its allure. In an article for RNS, Katelyn Beaty explored a few of the reasons that might be, highlighting the Gnostic component at work. Like all political cults, QAnon also seems to offer a strong sense of belonging to its proponents. You might say that loneliness + uncertainty + meaninglessness = cults. The Vice profile spells this aspect out well:

“This pandemic has created an environment of uncertainty and powerlessness within many aspects of human life today,” says a Media Diversity Institute report from June. “Unfortunately, QAnon has successfully taken advantage of this atmosphere by expanding the scope of the conspiracy theory and using it to spread misinformation and fake news about an already complex and unsolved public health crisis.”

Travis View, co-host of the popular U.S. podcast QAnon Anonymous, said he’s been watching groups pop up all over the world during the pandemic and sees it as a result of people needing community. At the end of the day, that’s what QAnon is: an online community. “QAnon seems like a primarily U.S. conspiracy theory but is actually a big-tent conspiracy theory movement,” said View. “So whatever sort of conspiratorial beliefs that you happen to latch on to, you’re going to find a home within QAnon.”

“What people get attached to more than anything else is the online community of people who don’t trust any kind of institutional knowledge,” he added.

3. On the more redemptive end, Rebecca Mead’s piece in the New Yorker on “The Therapeutic Power of Gardening” has much to recommend it (and horticulture itself!). Most of the article is devoted to profiling British psychiatrist and author Sue Stuart-Smith, who scored a surprise bestseller this year in the UK with The Well-Gardened Mind. Gardens, much like kitchens, often serve as venues for play and therefore healing (and grace):

In recent years, the benefits of gardening to mental health have become widely acknowledged in Britain. Primary-care doctors increasingly give patients a “social prescription” to do something like volunteer at a local community garden, believing that such work can sometimes be as beneficial as talk therapy or antidepressants. Some hospitals have been redesigned to incorporate gardens, spurred by findings that patients recovering from catastrophic injuries can heal more quickly if they have access to outdoor spaces with plants …

A garden, Stuart-Smith suggests, can be a Winnicottian “in-between” space that allows the inner and the outer worlds to coexist simultaneously — “a meeting place for our innermost, dream-infused selves and the real physical world.” The meditative and repetitive aspects of gardening can function as a form of play for grownups who have otherwise stopped playing — or who, like Stuart-Smith’s patient Kay, were denied the possibility of doing so safely as children …

Stuart-Smith writes, “When life forecloses on us, the lack of a sense of a future is the hardest thing to deal with.” Many people, when faced with their own mortality or that of their loved ones, become more attuned to the natural world. This is evidence not just of a garden’s power to distract and inspire but of its power to console through its cyclical replenishment …

Gardening has been a solace to so many, Sue Stuart-Smith suggested to me, because it invokes the prospect of some kind of future, however uncertain and unpredictable it may be. “When the future seems either very bleak, or people are too depressed to imagine one, gardening gives you a toehold in the future,” she said. It can also help reconcile us to the inevitability of our demise. At the Barn garden, [Sue’s husband and renowned horticulturalist] Tom Stuart-Smith told me that every spring, when the bulbs of fawn lilies and summer snowflakes are flowering and the meadow is full of narcissus, he goes around the garden with a notebook, to make plans about where to add things in the autumn. “I think a lot about next year, but I also think, absolutely, about what it’s going to be like when I am dead,” he said. The future promised by a garden may not always be ours to enjoy, but a future there will be, with or without us in it.

4. Next up, a heady but prescient one from a couple years ago, well worth the effort it takes to absorb. The philosophy journal Krisis interviewed German sociologist Hartmut Rosa in 2019, allowing him to lay out his theories on alienation and resonance, and, well, they resonate deeply with the whole #seculosity thesis. Alienation, in his mind, is mainly a function of what he calls acceleration:

[Rosa] considers modernity in terms of a broken promise: the very technology and social revolutions that were supposed to lead to an increase in autonomy are now becoming increasingly oppressive. In Alienation and Acceleration (2010) he even calls acceleration a totalitarian process, because it entails all aspects of our personal and social lives, and is almost impossible to resist, escape or criticize. Rosa writes: “The powers of acceleration no longer are experienced as a liberating force, but as an actually enslaving pressure instead” (Rosa 2010, 80) … While we feel the constant pressure of having to do more in less time, there also seems to be a shared feeling of a loss of control over our own life and the world, and therefore of losing contact with it […]

This has always been the promise of modernization and acceleration, that it will eventually give us freedom, but there has been a betrayal on both ends. On the one hand, it didn’t give us freedom: you can see the exact opposite … Every year we have to run a bit faster to keep what we have.

For some years I’ve worked with young people, just before their matura [secondary school exit exam, TL & RC], and each year we are talking about what they are going to do next. I think there has been a shift from about 20 years ago, where they would say “I want to do philosophy” or so, and now they come and ask: “what could I do if I study philosophy?” All our capacities, all our energies, all our dreams are fitted into the logic of increasing productivity […]

When you today talk with young people about the future it is very interesting that they think of it in technological terms: artificial intelligence, what will become possible to do and so on. That has changed a lot in comparison to the 1970s or 80s, when young people thought about the future in more political terms: let’s shape the future politically! …

What has been lost, however, is the promise it carried, namely that through these innovations in science and technology, life would become better. We would overcome scarcity, we would overcome ignorance and probably even suffering, we would finally know what the good life is and have the chance to lead it. No one believes that anymore, right? No one believes that we will overcome scarcity; it is rather the opposite, we believe competition will result in even more scarcity, so that in the future we will have to work even harder. No one believes that with faster technologies we will solve the problem of time pressure and we know that we won’t overcome ignorance. Precisely because of all the progress in science and technology, we now don’t know what to eat, we don’t know how to give birth — we don’t know anything. This promise that anything will get better has been lost.

The solution to all this acceleration-based alienation falls under the category of “resonance” — basically defined as any non-instrumentalizing relationship with other people, the world, even God, i.e. any relationship characterized by openness and responsiveness and, well, grace, rather than something tit-for-tat or law-based. Read the whole thing if you have the time.

5. Next, Tim Kreider wrote about what it means to have become a meme (above) and turned in a couple of paragraphs about identity and imputation that warrant memes of their own. Preachers take note:

The things people love about you aren’t necessarily the things you want to be loved for. They decide they like you for reasons completely outside your control, of which you’re often not even conscious: it’s certainly not because of the big act you put on, all the charm and anecdotes you’ve calculated for effect. (And if your act does fool someone, it only makes you feel like a successful fraud, and harbor some secret contempt for them — the contempt of a con artist for his mark — plus now you’re condemned to keep up that act forever, lest she Realize.) You don’t even get to know what your children will remember you for; it probably won’t be what you thought were the important moments. I still remember my dad snoozing next to me in the theater at a long, slow science fiction movie I was keen to see when I was 12. It still touches me to imagine how little interest he must have had in that film. He probably would not have wanted to be immortalized in his sleep, but there he is, snoring gamely beside me …

At some point you have to accept that other people’s perceptions of you are as valid as (and probably a lot more objective than) your own. (Leonard Nimoy wrote another book, 20 years later, called I Am Spock.) This may mean letting go of a false or outdated self-image, including some cherished illusions of unique unlovability. For years I felt guilty and fraudulent every time my girlfriend called me a good boyfriend until, eventually, I realized she’d actually made me one. It’s getting letters from readers or corresponding with fellow authors — certainly not writing or publishing books — that makes me feel like a real writer. And it wasn’t until I started teaching, and my students treated me as though I were an adult, that I noticed I’d accidentally become one.

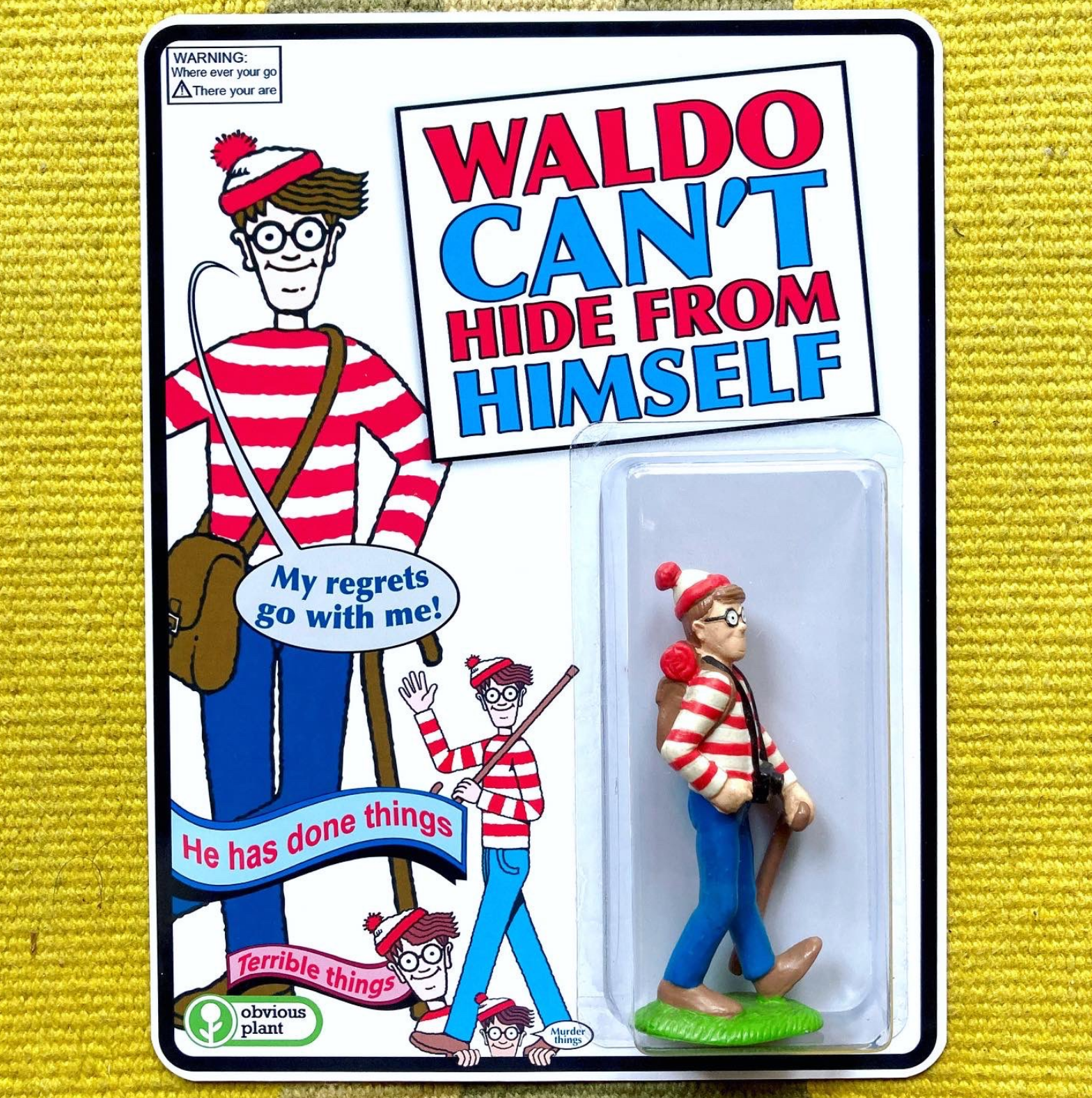

6. On the humor front, the featured image from Obvious Plant is my favorite thing I’ve come across. But The Hard Times made me chuckle with People Who Fight Against Cultural Appropriation Are My Spirit Animals and Small Liberal Arts College Releases Fall Semester Classes on Vinyl. McSweeney’s list of “Living with a Pandemic or a Newborn?” has some funny parts and the New Yorker‘s full-scale version of Kim Kierkegaardashian’s advice column was clever.

7. Finally, writing for the Atlantic, Carina Chocano asks a question we’ve all been wondering about, namely, “What is Masterclass Actually Selling?” The answer she finds has to do with, surprise surprise, enoughness. And cats (but not the movie thank God):

The company refers to its target customers as CATS: “curious, aspiring 30-somethings.” CATS are old enough not to be planning to return to school, but young enough, in theory, that they need help advancing in their career. A CAT is a person whose life has become complicated, who has had to put aside some of the things they loved to do, who isn’t exactly doing the thing they dreamed of doing, David Schriber, MasterClass’s chief marketing officer, told me. They’re anxious about their future, their present, their position relative to that of their peers. “They’ll talk about having anxiety that their co-workers or the people on their social networks all seem to know more about a subject than they do,” Schriber said, referring, presumably, to pre-pandemic focus testing. “Someone will come to the office party and talk about wine, and then they’ll feel like I don’t know enough about wine. Someone else will talk about photography, and they’ll be like Man, I should pay attention to who the photographers are these days. Or their boss will say things like ‘You need to work on your leadership profile, or hone your creative judgments,’ and the poor 30-something is like Where am I gonna get all this?” Something about this struck me as clammy and sad, as far away from They can’t take your education away from you as it’s possible to be. As though it’s revealing another layer of unpaid labor — cultural labor — one is expected to do in order to secure the privilege of performing actual labor.

Strays

- A very affecting rumination on middle age, lost tribes (“raptures of belonging”), and the similarities between punk subculture and Christianity in Plough, courtesy of Ian Marcus Corbin

- As HBO’s “Lovecraft Country” hits screens, church historian Philip Jenkins offers up an unexpected tribute to the controversial horror-meister, the last line of which is pretty darn inspired/hilarious.

- Greatly enjoying the new Killers record that dropped today, Imploding the Mirage. Come for the surging Springsteen-meets-Pet-Shop-Boys anthems, stay for the surprising guest stars (Lindsey Buckingham, Weyes Blood, KD Lang, Alex Cameron) and frequent grace-notes.

- Two podcasts to recommend. Our friend Blake Flattley launched a new creativity-focused one for 1517 called The Craft and it’s great. And while I haven’t had a chance to listen yet, word has it that the season premiere of The Cut’s cast deals with optimism in a refreshing and sympathetic way.

COMMENTS

One response to “Another Week Ends: Strange Rites, QAnon, Gracious Gardens, Accelerated Alienation, Imputed Memes, Masterclasses and The Killers”

Leave a Reply

Thank you Thank you Thank you!!!