This article is by Melissa Dodson:

Every year as April approaches, my husband and I, since we each own small businesses, enter the deep, mysterious waters of accounting, up to our necks in numbers, earnings, and expenses as we face the onerous obligation that tax season requires. With calculators close by, our kitchen table swims in stacks of receipts and details of potential deductions — enumerations from the ledger of our economic existence. We hold our breath for weeks until, finally unburdened, we receive the news that the money we’ve set aside is, in fact, sufficient to cover the amount we owe.

In our capitalistic culture we are all accustomed to life being spelled out in financial terms; the lenses through which we view the world are tinted monetary-green. Because of this the dynamics that characterize a whole spectrum of our relationships become, even unconsciously, transactional and contractual.

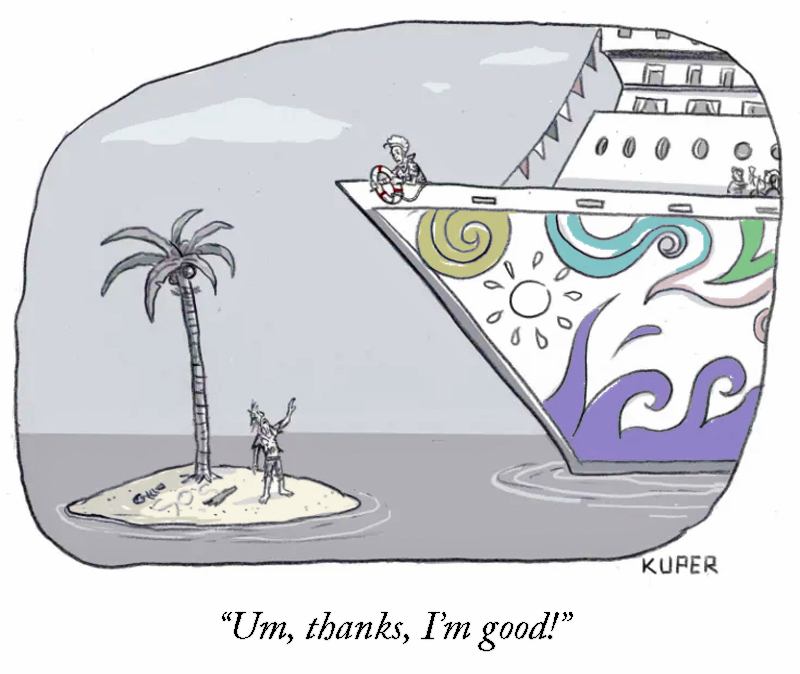

If I give, the rules of quid pro quo dictate my expectations for what I’ll receive in return. If I receive, I assume the giver is keeping close tabs on the equity of our interchange. Which might, in some cases, even lead me to avoid receiving. I don’t want to owe anyone.

Could this be one reason why the very idea of grace is so difficult for us to wrap our minds around? Not only do free gifts not make sense, we as humans don’t like to receive grace because we don’t like to feel indebted.

Henri Nouwen once expressed how “one of the greatest challenges of the spiritual life is to receive God’s forgiveness.”[1] So simply stated, yet so deeply true; we struggle to meet God in his embrace. While Nouwen could articulate various factors at play, surely one salient factor rises to the surface: to willingly receive something we haven’t earned elicits for us all kinds of questions and worries about who might be summing the tally of our debts.

I often wonder whether our reticence to receive from God is tied to our reticence to receive from anyone. After all, as difficult as it is to accept good gifts from the Lord, it can be just as tough for us to receive from other people.

One of several reasons for this is that we like control, and as long as we task ourselves as the givers of gifts, we maintain a sense of control. Also, we like power, and as long as we function as the benefactors, we maintain a sense of power. Plus, always giving means we aren’t left feeling the weight of indebtedness.

As a natural result, so often within our human relationships we come to envision our roles as the administrators of grace, not the recipients.

It’s as if we expect the river of grace to flow from God to our souls, then to continue downstream from our God-given fount into the lives of people we hope to bless. Not only is this perspective tainted by presumption and superiority, adopting such a mentality means that we could be ignoring — and missing out on — the grace that arrives to us from other people in our midst, reaching our spirits by way of quiet and unexpected currents.

It’s as if we expect the river of grace to flow from God to our souls, then to continue downstream from our God-given fount into the lives of people we hope to bless. Not only is this perspective tainted by presumption and superiority, adopting such a mentality means that we could be ignoring — and missing out on — the grace that arrives to us from other people in our midst, reaching our spirits by way of quiet and unexpected currents.

For Christians, does this tendency not pungently flavor our ways of relating to people in our communities, especially those to whom we expect ourselves to minister? We feel called to offer service, all the while exhausting ourselves in one-directional strivings. We feel called to offer benevolence, overlooking the benevolent love of others and what it could mean in our lives. Because of this, as undeserving beneficiaries of God’s grace, we are not fully allowing our own souls to experience — in vulnerability — the grace offered us by our fellow human beings.

Years ago, as a missionary in Central America among mango trees laden with sweet fruit, surrounded by a nearly perfect year-round climate, and amid people with far fewer material resources than I could claim, I experienced a crisis of identity. How could I — as a well-paid, highly-equipped missionary — be so deeply influenced by the welcoming embrace and hospitable care of the locals around me? Wasn’t that my job?

I had hoped to fix, to teach, to give, to solve, and to save, all the while I was looking past the gifts they had to share, the wisdom they had to impart, and the grace they had to bestow.

What if a posture of surrender — of humbly receiving without owing anything in return — was not relegated to our relationship with the Lord, but rather came to characterize the whole gamut of our relationships?

So, yes, with open hearts we could receive God’s love, but with those same hearts we could accept our neighbors’ kindness. Yes, with open hands we could receive God’s provision, but with those same hands could receive the care of other people. And yes, with open arms we could receive the unearned grace of the Lord, but with those same arms we could accept the welcome of those who surround us. We could sit around their tables, eat their food, listen to their stories, receive their ministry to our spirits, and be loved. Without ever owing a thing.

In fact, what if the terrain of surrender, grounded in a certain rest from all our strivings, became very familiar territory in the whole of our lives? As we die the death of our need for control, and as we die the death of our grasping for power, we could find ourselves approaching both God and our neighbors in weakness, knowing that none of us will ever know enough or give enough or do enough or be enough to deserve his acceptance.

In Christ, our un-deservedness is actually good news, since he threw out the ledger book ages ago … all the math just got in the way. He simply wants us … grace given, nothing owed.

COMMENTS

Leave a Reply