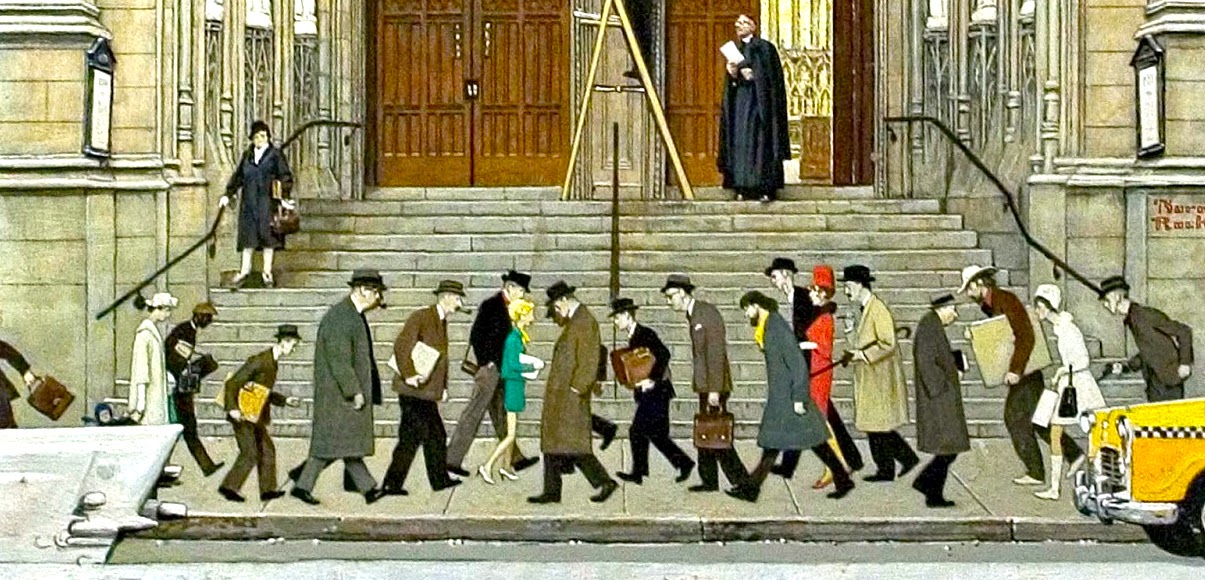

I received a remarkable gift for Christmas, the kind a grown man shares on Instagram. No, not the mint condition New Wave Dave that one brother gave me. I’m referring to something from the other brother, a print of Norman Rockwell’s 1957 painting, “Lift Up Thine Eyes.”

Perhaps you’ve seen it. In classic Rockwell style, there’s a conceit to it, almost a punchline. A New York City sidewalk filled with shuffling people, all staring at their feet while a church custodian places the final letters of that week’s message in the announcement box. “Lift Up Thine Eyes,” it reads, quoting Isaiah. The church is St. Thomas Fifth Avenue.

Perhaps you’ve seen it. In classic Rockwell style, there’s a conceit to it, almost a punchline. A New York City sidewalk filled with shuffling people, all staring at their feet while a church custodian places the final letters of that week’s message in the announcement box. “Lift Up Thine Eyes,” it reads, quoting Isaiah. The church is St. Thomas Fifth Avenue.

Rockwell’s vertical composition employs every trick in the book to draw the eye upward. The railings, the arches, the ladder, the birds, it’s all meant to underscore just how much the crowd is missing. Their posture obscures the vast majority of what’s there to see, not just God but, well, all the beauty and freedom on offer in the world itself, to say nothing of the faces of their fellow humans.

Some of the people look like they’re rushing somewhere, others look heavy-burdened and sad. A few just look distracted. I’m not sure it matters. I just know that their posture is the same as that of the Israelites that Isaiah was addressing two-plus millennia earlier — and of us today. Indeed, everyone who sees the painting notes how the subjects might as well have smartphones in their hands.

One can only assume that there’s something timeless and dare-I-say universal about human beings casting their eyes to the ground. Our default perspective is limited, either by choice or experience or biology or all of the above. Curved-in is how Luther put it, I think, and the diagnosis is apt.

A curved-in existence will be a lonely one. Not just because you never look other people in the eye, but because other people become obstacles to where you’re going.

Writing in the Atlantic last week Amanda Mull noted how “The Pandemic Has Erased Entire Categories of Friendship.” Her point was that health protocols have eliminated interactions with those on the periphery of our lives, the cumulative effect of which is worrying:

Friendly chats between customers and delivery guys, bartenders, or other service workers are rarer in a world of contactless delivery and curbside pickup. In normal times, those brief encounters tend to be good for tips and Yelp reviews, but they also give otherwise rote interactions a more pleasant, human texture for both parties, to have our own humanity reflected back at us […] Strip out the humanity, and there’s nothing but the transaction left.

Moreover, people on the peripheries of our lives introduce us to new ideas, new information, new opportunities, and other new people. If variety is the spice of life, these relationships are the conduit for it.

The danger of only interacting with people you know extremely well is that you get trapped in a kind of punishing sameness. And in terms of Rockwell’s painting, it’s a lot easier for those eyes to remain downcast when you (think you) know what’s going to come out of the mouths of your loved ones. No alarms and no surprises.

Mull is convinced that when life returns to “normal” we’ll be more grateful for all the casual relationships in our lives, and maybe so. But perhaps we’re already seeing a renewed premium put on friendships as a sustaining force. I loved the story, also in the Atlantic this week, about two middle-aged guys who have walked 30 minutes every week for the past six years to give each other a high-five. As life has dealt them ups and downs aplenty over that period, the high-fives have transformed from a sweet but minor gesture to a means of survival — and grace.

There’s something to be said for regular (embodied) interactions with those outside your household and/or office. A long-haul relationship with someone who doesn’t need anything from you beyond a fist-bump. I’m pretty sure this is why small groups in churches are so effective. The seemingly pointless get-together — the easiest thing to bail on — becomes the mast of the ship when the storms arrive.

Alas, such stories are newsworthy because they’re so rare. In practice, the pull of convenience and self-protection (i.e., control) seems to draw our eyes inexorably back downward. We scan the horizon for an easier way to get “the rewards of being loved without submitting ourselves to the mortifying ordeal of being known.” Basically, any format for connection where we don’t have to risk anything in order to gain some approximation of love.

Parul Seghal’s review of the novel I’m most excited to read at the moment, Lauren Oyler‘s Fake Accounts (it came out this week), captures this dynamic with devastating humor:

It was a punishment for Dostoyevsky’s characters to be tormented by all those voices, internal and external; now we call it being connected. “So many people,” Oyler writes, “talking, mumbling, murmuring, muttering, suggesting, gently reminding, chiming in, jumping in, just wanting to add, just reminding, just asking, just wondering, just letting that sink in, just telling, just saying, just wanting to say, just screaming, just *whispering*, in all lowercase letters, in all caps, with punctuation, with no punctuation, with photos, with GIFs, with related links, Pay attention to me!”

She’s describing a situation in which our need has rendered other people props in our quest for validation. Eyes planted firmly groundward. Probably goes without saying that social media is tailor-made for this pursuit; indeed, it has monetized that drive in, er, unprecedented fashion.

Along those lines, if you missed Shoshana Zuboff’s “The Coup We’re Not Talking About” in the NY Times last week, I can hardly think of a more important article to read, mark, learn, and inwardly digest. Prof. Zuboff gets underneath all the headlines — and how those headlines hit home in our hearts — in a way that’s by turns frightening and hopeful. Not to mention undeniable. Most of it boils down to…

Of course, we religious folks have our own way of keeping attention focused on our belly-buttons (and the feet rather than faces of those surrounding us). Church itself can become a means of avoiding the God of grace, depicted in the painting as doves/pigeons flying anywhere the wind takes them.

The religious impulse, instead, involves keeping God shackled firmly to the firmament. We do this chiefly by insisting that He remain a Cosmic Accountant, do we not? Perhaps the best takedown I’ve read of this impulse — and the wreckage it causes — comes in Taylor Caldwell’s half-bonkers/half-prophetic novel Bright Flows the River. The uptight protagonist, Guy Jerald, is speaking with his freewheeling father Tom, who sounds uncannily like Robert Capon. Tom tells his son:

‘A strictly virtuous and dutiful man or woman is a great sinner, in spite of Bible-shouting and going to church and living a “good” life — because they didn’t love. They sinned against God Himself, who is a God of Love.’

He paused. Guy had been listening intently and now his dark face was lighted by a brief smile. He said, ‘I guess, then, that God must love you a lot, you being a great sinner, Pa.’

Tom grinned anticly. ‘Well, I love Him, in my fashion. Most sinners do. Only the virtuous really hate Him in their hearts — they think He’s a taskmaster, full of hate too, for anything beautiful and joyous and delightful. And deep in everybody’s heart is the sure knowledge that joy is a celebration of the God of Joy. So, the “virtuous” deny joy because they think God is purely a God of wrath who must be appeased at any cost, thought they know, by instinct, that’s wrong … That’s what has always led to religious cruelty and persecutions — in the name of a God of hate — who doesn’t exist, anyway.’

Those who conceive of God as fundamentally a Taskmaster (or as Lawgiver rather than as both Lawgiver and Law-fulfiller) will keep their eyes down, thank you very much. Too scary to lift our gaze or open our hearts. Better to point out the failings of our neighbors — especially if it’ll keep the scrutiny off of us.

Alan Jacobs took a look this week at how this same “religious” impulse has found its way back into (not-so-) polite society in a brilliant post on what he calls “katharsis.” He’s after a more accurate way of describing what’s at work in the “cancellation” rodeo we see playing out all around us, a term which has itself been cancelled. He begins with an observation of “the prevalence among those committed to social justice, especially on our university campuses, of a sense of defilement.”

The very presence in one’s social world of people who hold fundamentally wrong ideas about race and justice is felt as a stain that must somehow be scrubbed away. As long as such people are present, one experiences akatharsia: impurity, defilement. The filth must be cleansed, the community must be purged. (I’m choosing the spelling “katharsis” rather than “catharsis” to focus on this archaic meaning.)

This kind of thing is sometimes referred to as scapegoating, but it isn’t, not at all. Essential to scapegoating is the belief that the unclean social order can be made clean by casting out or sacrificing something that is itself pure and undefiled. In the cases I am discussing here, the logic is more straightforward: the one who is perceived to bring the defilement must himself or herself be expelled. Scapegoat rituals have a complex symbolism. Katharsis culture doesn’t.

Jacobs’s reframing went a long way toward helping me understand our culture’s recent reversal on the artistic merit of transgression, which Laura Kipnis reflected on somewhat definitively here (and I, in my own way, tried here).

You’ll note that the further up one rises in the Rockwell painting, the cleaner and less defiled the surroundings. Meaning, if you’re only looking at the shoes of the person in front of you — and the stains on the sidewalk — all you’ll see is defilement. God help you if you look too closely in the mirror.

Speaking public purgation, former New Republic editor Leon Wieseltier penned a tsunami of a column for Liberties journal about the hunched perspectives we all inhabit, for both better and worse:

One of the consequences of recent social movements in America — #MeToo and Black Lives Matter — has been to reveal how poorly we understand each other. Or more precisely, they have exposed the extent to which the failure to understand others may be owed to the failure to understand oneself — the limitations of one’s own standpoint, the comfortable assumption that one appears to others as one wishes to appear to them, or to oneself. This is nonsense, though sometimes you learn so the hard way. There are limits to our epistemological jurisdiction. The failure to observe these limits is solipsism, and we all begin as solipsists, awaiting correction by social experience. Our epistemological jurisdiction stops at the encounter with another person […]

The enlightenment that one acquires from the judgments of others is owed only to their accuracy. It is certainly not warranted by the belief that a person’s identity or socio-economic position or experience of hardship confers an absolute authority, a special relationship to truth, a vatic privilege. What a simple world it would be if pain were a sufficient guarantee of credibility. But it is not — indeed, the opposite is the case, pain is myopic and sees chiefly itself, which is one of the reasons it hurts. Finally we are all left with the modesty of our grasp. No whole classes of people are right and no whole classes of people are wrong.

The ineradicability of ambiguity from human relations, the ignorance of ourselves that accompanies our ignorance of others, the whole fallible heap, creates an urgent need for tolerance and, more strenuously, for forgiveness. Historians will record that in the early decades of the twenty-first century we became an unforgiving society, a society of furies, a society in search of guilt and shame, a society of sanctimonies and “struggle sessions” American-style. They will admire our awakening to prejudice but lament the sometimes prejudicial ways in which we acted on our progressive realizations. In this respect America should become more Christian. (There, I said it.) For all our elaborate culture of self-knowledge, for all the hectoring articulateness of our identity vocabularies, we are still, each of us, our own blind spots. We should welcome every person we meet as a small blow against blindness.

Amen, amen. And yet, as the Rockwell painting illustrates, much as we “should” welcome those standing in front of us, we seem curiously bound to own vacuum-sealed horizons, even on the busiest of streets. At least AirPod junkies like yours truly are.

So how does a person ever lift up their eyes? What makes a hunched-over person stand up straight? Does it ever happen?

Yes, but not through better architecture (alone). Nor does it happen via exhortation. Lord knows Isaiah himself repeated the painting’s injunction over and over again, but it wasn’t enough to produce faith in those grumbly Israelites. That tactic won’t work with you or me either. Neither will behavioral science, apparently.

Since it’s Superbowl weekend, I say we consult America’s new favorite coach, Ted Lasso. Hopefully you’ve had a chance to watch the show at this point — one of the out-and-out highlights of pandemic viewing. We’ve posted on it a couple of times before. If you haven’t seen it yet, here come some spoilers.

Ted Lasso is a comedy on Apple TV about an American college football coach who is hired by a professional English soccer team. Ted, it would appear, knows next to nothing about soccer, and during the first episode viewers could be forgiven for thinking they were in for some massive culture-clash satire, with the American in the stereotypical role of naïve bumpkin. We soon find out that great coaches don’t have to know the sport if they know … people. And Ted Lasso knows people.

One of the first people he meets is a lowly clubhouse attendant named Nathan. A clubhouse attendant does the laundry, picks up after the players, gets them tea, etc. — the lowest person on the totem pole. This young man is clearly not a confident person, reflected in his quiet, hunched demeanor. We soon discover that he’s dumped on by the team relentlessly, made to ride with the luggage, stuffed into lockers, that sort of thing.

And so he is taken aback when Ted asks him his name. “Nathan,” he responds, looking up for the first time.

Ted immediately dubs him Nate the Great, and you can tell that Nathan is thoroughly puzzled by the affection. As the season progresses, no one else is really willing to help Ted find his footing, so Nate the Great becomes his go-to. Ted is either unaware of, or chooses to ignore, the established hierarchy. Slowly, but surely, we watch as he draws Nate out, giving him more and more respect and responsibility until eventually Nate is enlisted to deliver a major locker room speech. He’s standing tall and speaking loudly for the first time — all because of this remarkable coach, who everyone thought didn’t know what he was doing.

The kicker comes a few days after the big game though.

Talk about being lifted up! All of a sudden, where once there was an atomized collective of contracted players that detested each other, you now have the opposite of loneliness. A team! The walking stain on their pride hasn’t been cleansed but redeemed.

Or you could just say that what Nate thought was going on, and what was actually going on, were two very different things. This funny coach, who, according to the team’s oh-so-limited perspective, looked so aloof and hopeless, knew what he was doing after all. And what he was doing was providing a glimpse of the same God that Isaiah tells us about in that passage, the God who “gives power to the faint, and strengthens the powerless.”

Ted understands instinctively that only grace, or intervening love, has the power to lift up the countenance of those bent lower than grasshoppers.

Nate’s downcast gaze was interrupted by the arrival of something new and unexpected. Something from the other 5/6 of the canvas, in this case a goofy mustachioed American who lays down his authority for the sake of those who resist his every move.

Now that’s what I call a coup.

Strays

- No new episode of The Mockingcast today but we should have a fresh one next Friday.

COMMENTS

4 responses to “Norman Rockwell, Ted Lasso, and Isaiah’s Coup de Grâce”

Leave a Reply

This was all so great. Thanks, Dave!

I’m reading Surveillance Capitalism right now. Did this video placement of Shoshanna Zuboff explaining her book show up accidentally? Or is Dave surveilling my ebook purchases? The mind boggles…

This was a great read, Dave. Love the new format for the weekender. ????

Thank you <3

That last paragraph (and the entire post, really, but especially) encourages me~