There’s a moment in the final episode of Pretend It’s a City, Martin Scorsese’s fantastic new Netflix mini-series about Frannie Lebowitz where the renowned critic and humorist says something controversial. It’s one of many such moments, in fact, but this one stuck with me.

She’s talking about whether one should or shouldn’t consume art made by people who’ve done terrible things. It’s a pressing question these days, usually expressed in terms of separating the art from the artist. Does the transgression of the creator invalidate their creation? (You’ll note that no one ever argues the inverse, i.e. that the virtue of the artist enhances their art.)

As in most things, Frannie doesn’t hesitate to express a strong opinion. She tells us she’s happy to read books written by scoundrels like Henry Roth or listen to music conducted by villains like James Levine. She thinks other people should be too, considering how good the work itself is.

She concedes that you might not want to give money to such people or spend time with them. She’s fully supportive of someone like Levine losing his job. But to ignore or even seek to erase their art is, in her mind, a waste.

Now people say, ‘You can’t listen to [Levine’s] recordings without thinking of [the sex abuse allegations against him].’ I think, ‘Well, you can’t but I can.’

I watched the episode in question the same week that Phil Spector died. Even if you don’t know his name, you’ve heard the man’s music.

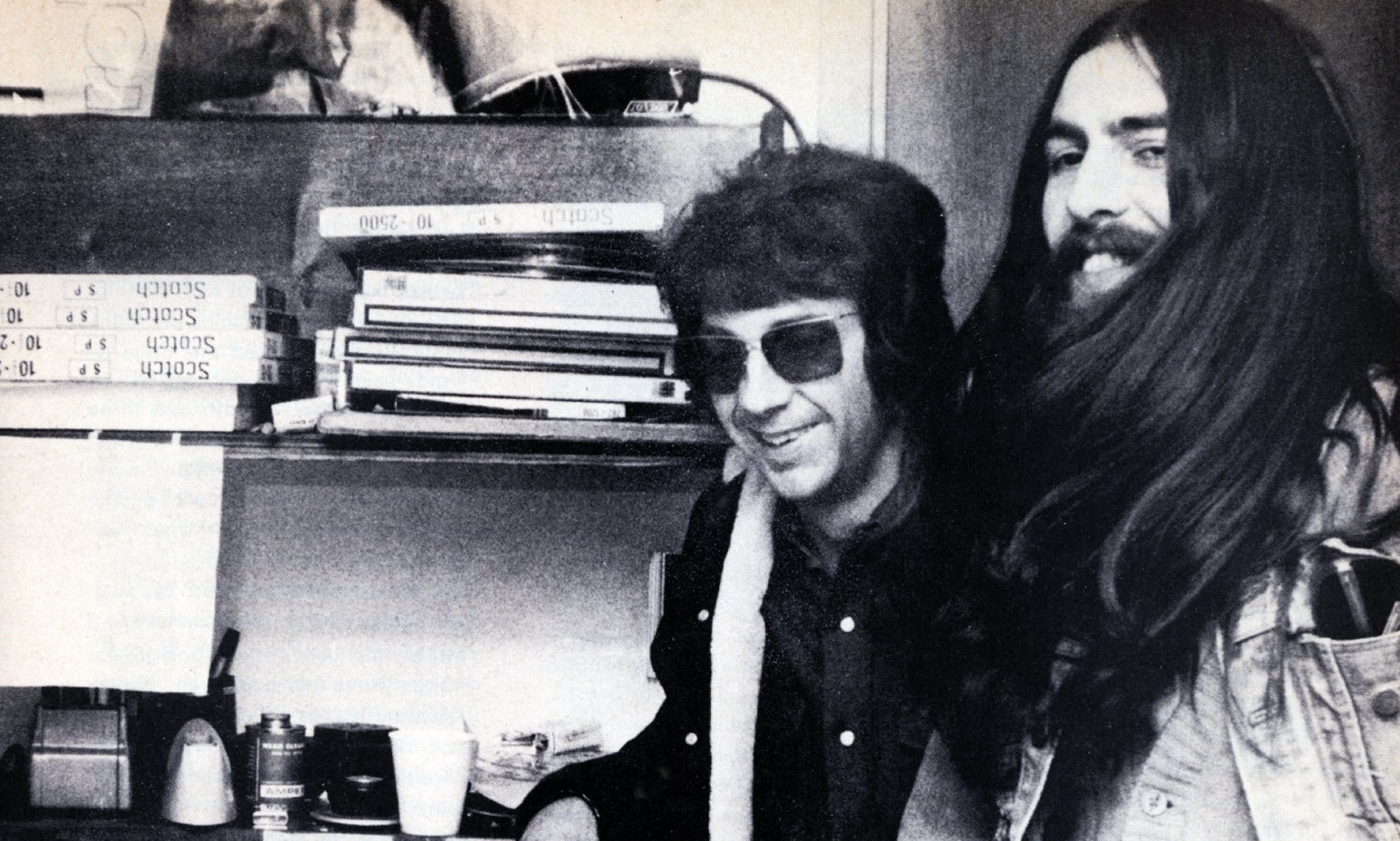

Spector was the ’60s record producer who put the “mad” in “mad scientist.” His influence over the development of pop music as we know it cannot be overstated. The Beatles, Bruce Springsteen, Brian Wilson, the Ramones, all of these artists considered him a primary influence and sought to emulate his trademark “wall of sound” in many of their recordings. (No Spector, no “Born to Run,” for example). Donald Glover made a whole episode of ATL about him as recently as two years ago.

Spector looms large, and if you listen to the singles that made his reputation — “Be My Baby,” “Christmas (Baby Please Come Home),” “You’ve Lost That Loving Feeling,” “River Deep Mountain High” — you’ll understand why. The teenage symphonies he crafted overflow with a joy and feeling that will long outlast the man himself. Infectious little pockets of American perfection. He is largely responsible for two of my favorite albums ever, George Harrison’s All Things Must Pass and Dion’s Born To Be With You.

Yet Spector was also a convicted murderer and by all accounts a highly abusive presence. He took advantage of pretty much everyone who recorded for him (except the Beatles) and showed little to no remorse about any of it. A megalomaniac of legendary proportions.

You can actually hear the vibe sour as his mental health deteriorated over the course of the ’70s, on claustrophobic productions like John Lennon’s Rock n Roll or Leonard Cohen’s Death of a Ladies’ Man.

A very mixed bag in other words, impossible to eulogize but impossible to ignore, pretty much the archetype of someone who is a finer artist than a human. The obituaries have been exercises in tightrope-walking.

So what does it say about me that I not just dig but adore his work? That his (rightful) conviction for killing Lana Clarkson didn’t have the slightest impact on my affection for those recordings? Am I that callous? I hope not.

I suppose I could disavow Spector in public, but that would be a pose. Spotify stats don’t lie: I can’t get enough of his stuff, especially the later output, and am not about to deprive myself of it. Life is too lacking in transcendence as it is. In today’s parlance, “the heart loves what it loves.” No doubt I would feel differently were I a sibling of Lana Clarkson.

Still, his death represents an opportunity to explore these questions afresh. Consider what follows an extended rationalization if you must, but this subject isn’t going away any time soon.

I’ve wondered if perhaps there’s a darkness in his catalog that resonates with me, below the level of consciousness. Maaaaybe, but I don’t think so. The predominant sensations I associate with Spector’s music are enchantment and romance, not malevolence. I listen to the Crystals and think about kissing people not hitting them.

Perhaps there’s a generational component then. After all, I grew up on a steady diet of rock n roll, so it feels pretty bizarre to expect moral rectitude from an artist in the first place. We used to make fun of rock stars with consciences. People like Bono or Bob Geldof. They were in the wrong profession, we claimed. Madonna was a bad girl — that was the whole point. Or at least a big part of it.

Moreover, writers and poets and comedians were supposed to be low-lifes. We certainly never expected them to be role models. I think of someone like Eddie Murphy, arguably the greatest stand-up of his generation. I still can’t repeat most of his jokes.

Of course, there’s a difference between a junkie and an actual murderer, between self-indulgence and outright criminality.

Is my affinity for all things Spector, then, just a matter of compartmentalization à la Lebowitz’s comment (“you can’t but I can”)? Possibly. I’m definitely not afraid of absorbing something toxic through my earbuds — nothing that’s not already there. Mark 7 only grows in stature the older I get.

And yet, when I listen to Spector’s recordings, I’d be lying if I said the man’s personhood didn’t impact the consumption somewhat. They’re not completely separate. The mythology of the mad visionary adds to the experience, for sure. It lends the music an air of fractured grandeur. It’s the missing ingredient in many of the knock-offs out there.

Perhaps the answer lies not so much in separating the art from the artist as in bringing them closer together.

That someone as damaged and malign as Phil Spector could produce such sublime music is an example of, well, grace. Just as the most kind-hearted people are still capable of sudden malice, goodness and beauty can — and frequently do — flow through the worst of sinners. Talent, it would seem, is not apportioned out according to “deserving.” At all.

The awkward truth is that beauty does not require piety or even repentance. If it did, there would be very little of it in existence. Instead, like so much in God’s world, it is fundamentally gratuitous. There is no formula for its summoning, no guard against its descent. Which is both maddening and comforting.

Maddening because it feels so unfair, so utterly beyond our control. But comforting because if inspiration of this magnitude arrives like a gift, unbidden and independent of the virtue of the recipient, that means it might come to someone like me. Or you.

Or da doo ron ron.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8vs6e8l6m9w

COMMENTS

6 responses to “The Miracle of Great Art (by Bad People)”

Leave a Reply

Good reflection! I have always found it interesting to note that the sons of Cain are the first documented artists and musicians.

Also, now that I know Scorsese directed the mini series, I’ll have to check it out. Btw…being a child of the 80s, I have Eddie Murphy ‘Raw’ memorized…but only have select friends with whom I can exchange bits of his routine…????

great piece. reminds me of the whole Louis CK fiasco. as disturbing of a person he might be, can’t help but laugh at a good joke.

Masterful!

Absolutely so !

I am recalling (dimly since it’s now 20 years ago…) from college a professor in a ancient Greek/Roman art and architecture class discussing how the ancients often associated closely the beautiful (in art) with the good, philosophically speaking. I’m oversimplfying it a great deal, but I remember discussions about how in the ancient world aesthetics was meant to embody an ethic. I’m not sure where that leaves the artist him/herself exactly. It’s a nice idea, and likely even in the modern age we hold onto it a bit, but we also know that it doesn’t always work that way. But a poor ethic doesn’t necessarily result in bad aesthetics…?

This is something I have thought about a lot with Kevin Spacey. I love the films, but man…