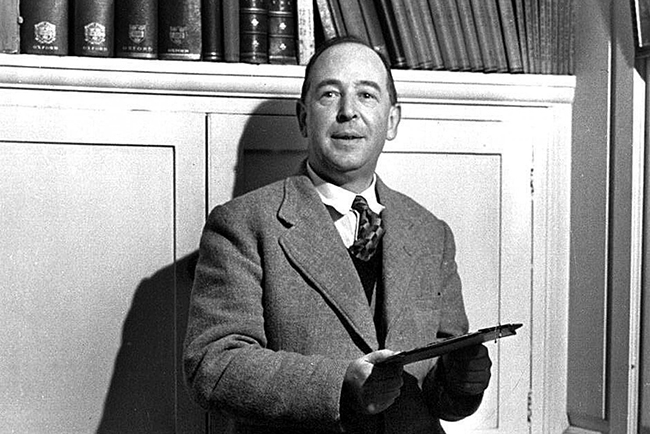

November 22nd is an exciting day for me and for many others as it marks the commemoration of the blessed Clive Staples Lewis in the church calendar. Lewis (“Jack,” as he was affectionately known to friends and family) needs little in the way of introduction: defender of the faith, author of the Chronicles of Narnia, poet, literary critic, Inkling, the scholar who unapologetically writes for children and the adults who never relinquished their capacities for wonder. But besides those things he is the saint whose words made the consolation of the gospel not only intelligible but irresistible, to me.

Lewis was skilled in recognizing breaches in formal logic, but what truly sets him apart from other apologists is the tenacity with which he clings to and asserts the emotional heart of Christianity. In his books, his radio broadcasts, and his extemporaneous lectures Lewis exemplified the inconsolable longing at the core of our race which Christ longs to fulfill in us. Lewis bore witness to “that of which Joy was the desiring” (Surprised by Joy) and wooed many, myself included, to go all in on the adventure of Christian faith. Dogmatics wasn’t his enterprise; Lewis was an admirer and teacher of medieval and Renaissance texts by profession, but the avocation placed on him by our Lord was to entice and encourage as many as would listen with all the potent powers of his imagination. Jack’s purpose in all he wrote and said therefore wasn’t to map the hinterland of Christian faith, but to condense into verbal icons the heart’s reasons for faith.

Reading Lewis’ books never fails to set my heart on fire — his prose is always pulsing with vitality, insight, and reverence for mystery. The evidence and arguments he adduces are only ever in service to this central tenet: that humankind was created to enjoy God and be enjoyed by God. This primal purpose finds its echo in the unrequitable nostalgia our desires awaken within us as the objects of our desires draw us up short. We are born with unquenchable appetites for joy, which God intends to satisfy. Our lifelong quests for unattainable satisfaction intimate a further depth dimension to reality that, as creatures, we cannot fully penetrate to. This is the most poignant signpost to the truth of our being. As he writes in The Weight of Glory,

Our lifelong nostalgia, our longing to be reunited with something in the universe from which we now feel cut off, to be on the inside of some door which we have always seen from the outside, is no mere neurotic fancy, but the truest index of our real situation. And to be at last summoned inside would be both glory and honour beyond all our merits and also the healing of that old ache.

And in The Four Loves,

Our whole being by its very nature is one vast need; incomplete, preparatory, empty yet cluttered, crying out for Him who can untie things that are now knotted together and tie up things that are still dangling loose.

“The very nature of Joy makes nonsense of our common distinction between having and wanting,” he wrote in Surprised by Joy. “There, to have is to want and to want is to have. Thus, the very moment when I longed to be so stabbed again, was itself again such a stabbing.” The longing which spurs us on to all that we will ever do always outstrips those things, yet so scintillatingly that even the memory of what we no longer have and can never recover is tinged with an incandescent sweetness. These descriptions evoke a delicious heartache too serious to be Romantic and too luminous to be Puritanical. They are unique among modern Protestants and uniquely speak to the bereavements of the modern West.

And so Lewis implored his secularized listeners and readers not to presume to judge God’s designs by their own flawed standards and suspicions. “There is no good trying to be more spiritual than God,” Lewis said in Mere Christianity. “God never meant man to be a purely spiritual creature. That is why He uses material things like bread and wine to put the new life into us. We may think this rather crude and unspiritual. God does not: He invented eating. He likes matter. He invented it.”

Lewis helps us resist the counterfeit virtues of growing up. He commends to us the humility of starting anew, of embracing the dependency innate to our being and adopting the self-forgetful posture of children enraptured with play. The gospel promise of rebirth makes childlikeness reasonable rather than something to be renounced. The kingdom of God, Jesus testifies, can only be spotted, can only be appreciated, if one becomes as a little child. If one must be born again, then it follows that a certain type of adulthood is ruled out — a type that most of us, if we were honest, we’d be happy to jettison if we were given the freedom to do so.

Lewis was happy to oblige the Lord’s invitation. He was, after all, the Oxford don who loved fairytales and children’s literature; he made no pretense of being too mature for them. “When I was ten,” he writes in “On Three Ways of Writing for Children,” “I read fairy tales in secret and would have been ashamed if I had been found doing so. Now that I am fifty I read them openly. When I became a man I put away childish things, including the fear of childishness and the desire to be very grown up.” Genuine maturity savors proper enchantment and is nourished by it.

Every gnosticism, after all, is the invention of “sensible” adults attempting to be spiritual on terms they deem more rational than God’s. Matter matters, and joy matters, and desire and memory and the scents and tastes and loves which have filled out our senses of what is to be clung to in life and of what makes its distresses and disappointments worth enduring — all of them matter. Perhaps Lewis’ greatest strength as an apologist was in simply insisting that our desires, not only to be renewed and made whole but to go on desiring amidst the flux of the world, are an indicator of our status as pilgrims pining for our true home.

This twinned concentration on the real and the wonderful and his commitment to not trying to be more spiritual than God is what separates Lewis from many would-be communicators of the gospel, in his and in our time. He absolutely disavows fundamentalist withdrawal but also will not accept any easy progressive certainties which identify the present with what God is about. Neither one waits for the God who draws near but always remains distinct from his creation. Distinct from but committed to; the inconsolable longing that characterizes humans’ existence is experienced in and through the things of this world, because those things are linked to, somehow participate in, the incomparable, unoriginated goodness of Jesus Christ.

But it’s not that there are more pious enjoyments hidden behind the screen of this scrap heap we are condemned to exist within. There is no screen. The universe isn’t a testing facility to be mothballed when Heaven arrives. It isn’t an allegory for something more real than it. The created things are good, the enjoyments real; just as real as the Lord behind and above and within them. The universe is deeper and fuller than we are ever able to make out. That created things are not ultimate things isn’t a disparagement of them: it’s simply telling the truth that the pleasures which awaken and stoke our appetites for He who is beyond them are disappointments as gods.

“These things — the beauty, the memory of our own past — are good images of what we really desire; but if they are mistaken for the thing itself they turn into dumb idols, breaking the hearts of their worshipers,” he cautioned in The Weight of Glory. Delight in these things, Lewis implores, but do not substitute them for God, else their delight will dissipate and die — as will we.

I admit that part of me is bothered when other Christians name Lewis as their favorite theologian, but it certainly isn’t because of any deficiency in his method or his conclusions. It’s just that he isn’t, properly speaking, a formulator of doctrine — he was always the first to demur that he was no such thing. What he was was a skilled analyst of the human heart and cartographer of the human imagination, one who was sufficiently fluent in the Christian tradition so as to direct his listeners’ and readers’ needs and desires to the God revealed in Jesus Christ. And having traversed the terrain between unbelief and belief, he became skilled in diagnosing the myths that strangle our desires and our capacities for wonder. The one genuine solution to our ills was the myth-become-fact of the incarnation. For only in Christ, the eternal meeting ground of God and humanity, is the severance between us and God overcome and our self-estrangement healed. Only in him is our destiny fulfilled and our inheritance opened to us once more.

When discussing Lewis, there’s always the danger of focusing too much on too small a selection of the texts and simply copying the same beloved, well-known quotations. I’d like to conclude this with the closing paragraph of his essay, “Dogma and the Universe,” as it captures the numinous experience of God drawing near, which Lewis himself suddenly underwent and which launched his own pilgrim’s regress:

When any man comes into the presence of God he will find, whether he wishes it or not, that all those things which seemed to make him so different from the men of other times, or even from his earlier self, have fallen off him. He is back where he always was, where every man always is. Eadem sunt omnia semper. Do not let us deceive ourselves. No possible complexity which we can give to our picture of the universe can hide us from God: there is no copse, no forest, no jungle thick enough to provide cover. We read in Revelation of Him that sat on the throne “from whose face the earth and heaven fled away.” It may happen to any of us at any moment. In the twinkling of an eye, in a time too small to be measured, and in any place, all that seems to divide us from God can flee away, vanish leaving us naked before Him, like the first man, like the only man, as if nothing but He and I existed. And since that contact cannot be avoided for long, and since it means either bliss or horror, the business of life is to learn to like it. That is the first and great commandment.

Thank you, Lord, for our blessed Jack, evangelist of the burning heart. Now let us keep the feast!

COMMENTS

2 responses to “C. S. Lewis: Evangelist of the Burning Heart”

Leave a Reply

I started re-reading the Narnia series this month for the first time since I was a child. I’ve found myself moved and impacted more than I expected, probably because, as you write, is a “skilled analyst of the human heart and cartographer of the human imagination.” His writings propel me to be more curious, more tender, and more receptive to the surprising and creative ways God is moving in the world and in my life. Thanks for this reflection!

[…] Spufford is not C.S. Lewis — he told us so himself at our 2014 New York Conference. If Lewis is the great apologist for the reasonableness of Christianity, the gift of Spufford’s Unapologetic is that it […]