Across the street from our condo building there is a small church with a big front lawn. Every December they set up a live nativity scene staffed by volunteers from the parish. It’s a lo-fi production, with little concern for accuracy or theater: there are dogs dressed as sheep, Joseph is wearing glasses, Mary is like 42 years old, and the magi are in costume robes, plastic royal crowns, and dad sneakers. (But there’s free hot chocolate inside, and hot chocolate has a way of rendering all the anachronisms insignificant.)

Tomorrow is January 6, the day on the church calendar known as the Epiphany. It is the day after the twelfth day of Christmas and it marks the beginning of something new in the story of Jesus. In a technical sense, Epiphany refers to the manifestation of Jesus to the Gentile world, exemplified by the story of the magi making their way to see the Christ Child, Epiphany’s central text. And the magi, as we’ll see, do not belong to the religious tradition of Mary and Joseph. They are outsiders, dressed in strange and foreign ideas about the universe, exotic and suspect; yet, they hold a place in the story, they have a seat at the table. Joan Chittister describes the scene, saying, “The world recognizes the heavenly in this tiny Child. And the Child recognizes the people of God in them. This is not a Christian child only; this child belongs to the world.” (The Liturgical Year, p.92)

What do we do with the story of the magi and what does their presence in Matthew’s story have to say to us today.

Outsiders

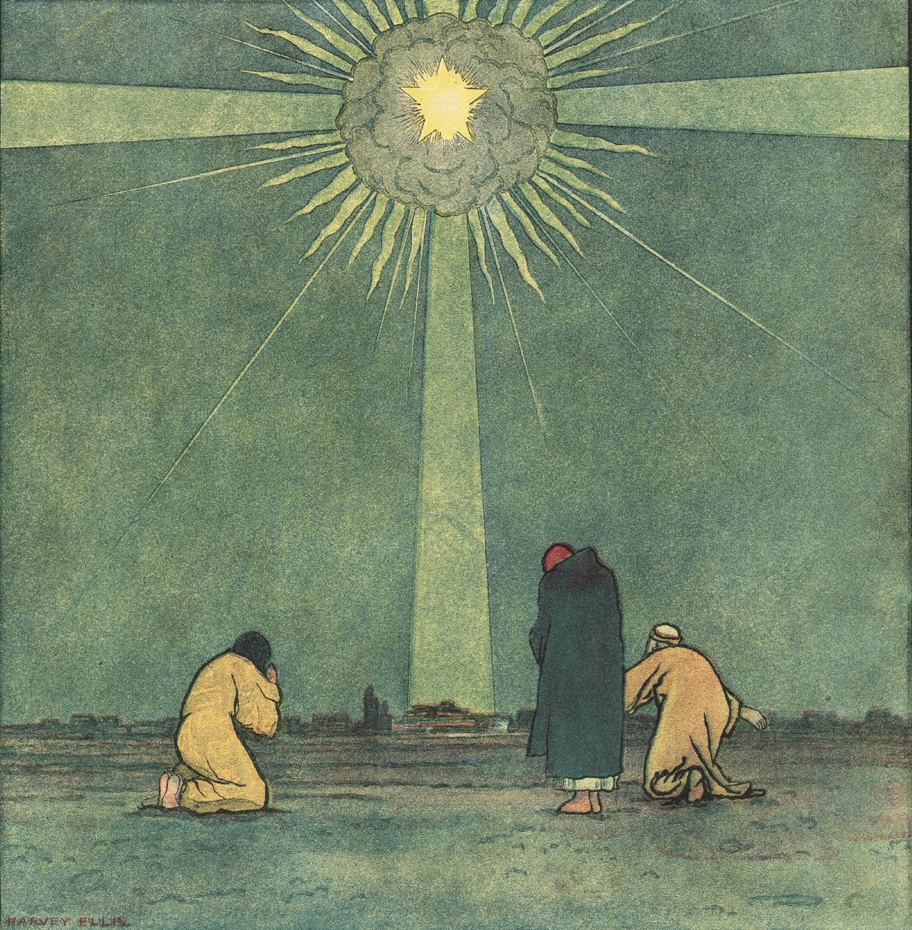

Now after Jesus was born in Bethlehem of Judea in the days of Herod the king, behold, magi from the east came to Jerusalem, saying, “Where is he who has been born king of the Jews? For we saw his star when it rose and have come to worship him.” (Mt 2:1-2)

The magi weren’t kings. We also don’t know if there were 2 or 20 of them at the scene. And we certainly don’t know their names. The numeration of three magi and their names (Balthasar, Melchior, and Gaspar in the West) are the myths of Church history, and they’ve played a significant role in muting what was really going on in the narrative.

The magi were an ancient sub-group of Persian priests, serving in the cabinet of whoever the ruler of the day happened to be. Daniel 2:2 names them as advisors to the Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar, who summoned them to interpret his dream. They had access, like a press pass, to various centers of power (which helps make some sense of their ability to walk right into Herod’s presence). Their affinity with astrology has made them famous, but their use of such a practice often left them shunned and even feared. They interpreted the movements in the skies against events here on earth, making predictions about the rising and falling of rulers and kingdoms, and ancient historians and philosophers weren’t always convinced.

The Roman historian Tacitus (56-120 AD) called magi “absurd.” The Stoic philosopher Seneca (4 BC-65 AD) said of the magi, “On even the slightest motion of heavenly bodies hang the fortunes of nations, and the greatest and smallest happenings are to accord with the progress of a kindly or unkindly star.” He poked fun at the magi’s ongoing prediction of Emperor Claudius’ death, pointing out that they had been calling it “every year, every month.” For some, the magi’s future-telling ways were unsettling. Emperor Tiberius (42 BC – 37 AD) had the magi expelled from Rome, a move to eradicate the annoyances and fears that come with bad news.

The magi’s worldview was not looked upon with great approval from within many of the ancient Jewish communities, either. Later Rabbinic writing warned that “He who learns from a magus is worthy of death.” Magi were strange and off-centered people, with weird views of how the universe worked; and to see the stars as divine messengers was not something the Hebrew people involved themselves in. (The sun, moon, and stars were considered gods in the ancient world, each with its own proper name. In the Genesis 1 narrative, they are simply called “lights”, a humorous and subversive demotion of their cultural and religious significance.)

And yet, here we are.

Right here in the nativity scene Matthew tells of how something in the night skies caused these religious and cultural and national outsiders to caravan themselves to Bethlehem to see Jesus. Something in the skies caught their attention and they acted on it. And most remarkably, Matthew retells the story not in a negative light, but in a positive one.

Windows

Every one of us sees the world through a certain window, a certain view of reality. The panes on the glass give framing to how we interpret the world around us, and how we experience what we see during our days here on earth. And the windows are innumerable. We see and interpret the world around us through windows of science, philosophy, religion, atheism, wellness, fear, control, politics, and too many more to mention.

The magi lived with a particular view of reality, they gazed at the world through a certain window. In the story, God knocks on their window. It’s that simple, and that scandalous. This knock was more of an invitation than a correction of thinking or a call to change what they believed to be true about the world – God simply tapped on their lens, saying, in their own cosmic language, “I want to show you something you wouldn’t expect.”

I imagine a group of local psychics turning up in my church building on Easter, saying, “We got a strange reading in the cards, and it brought us here.”

God knocks on windows. And not just on church windows.

Let Them In

By the time Matthew’s Gospel account was written, the early Christian communities were becoming a kaleidoscope of people, a socially mixed-bag of class and race and gender and political leanings. What started out as a solely Jewish movement soon became a more multi-layered testing ground for relationships across all sorts of societal dividing lines. As beautiful as that sounds on paper, it was not (and is not) an easy venture. The learning curve for community with others who were different – even disliked – was steep and arduous. (So much of Paul’s correspondence with churches focused on the practice of learning to live together in grace and in peace.)

At a time when churches can seem more like isolated clubs of like-minded affinity groups, Epiphany arrives as a disruption and a reminder of a different calling. How easily we forget that we were once magi too.

The Church Year is not random. Its seasons flow together. The paving stones of Lent that take us to Easter Sunday lay at the bottom of Epiphany’s stairs, a descent through the story of the universal Jesus and his open-door policy for all who seek him. Before one trods downward on the Lenten road, we are handed the implications of the coming resurrection. We are clothed for the journey in the colors of love and invitation, of good news for all the people. In a wonderfully challenging way, the magi are a reminder to let the people in, that the gospel is for the weird, suspicious, and despised.

Let them all in.

COMMENTS

3 responses to “Why the Magi Matter”

Leave a Reply

“In a wonderfully challenging way, the magi are a reminder to let the people in, that the gospel is for the weird, suspicious, and despised.

Let them all in.”

Beautiful reminder.

Thank you for sharing.

Thanks for this great exegesis! I can see new connections between these magi texts and the origins of the enlightenment tradition of “equal human dignity”. It’s interesting that we’re now living in an age where this tradition is being divorced from its Christian roots, and I can sort of see how it is beginning to fray… that tribalist division between ‘pure’ and ‘impure’ is returning in all sorts of ways to our political conversation.

Thank you for this article. I love the line, “I want to show you something you didn’t expect.” Where is the image from? It’s gorgeous.