1. Kicking off this week, we begin with an article that scared the bejeezus out of me, so much so that I immediately deleted half of the apps on my phone. Writing in his Substack, Ted Gioia offers his now yearly “State of the Culture,” and … it’s looking pretty bleak.

We’re witnessing the birth of a post-entertainment culture. And it won’t help the arts. In fact, it won’t help society at all. Even that big whale is in trouble. Entertainment companies are struggling in ways nobody anticipated just a few years ago. […]

This raises the obvious question. How can demand for new entertainment shrink? What can possibly replace it? But something will replace it. It’s already starting to happen.

The fastest growing sector of the culture economy is distraction. Or call it scrolling or swiping or wasting time or whatever you want. But it’s not art or entertainment, just ceaseless activity. The key is that each stimulus only lasts a few seconds, and must be repeated. It’s a huge business, and will soon be larger than arts and entertainment combined. Everything is getting turned into TikTok — an aptly named platform for a business based on stimuli that must be repeated after only a few ticks of the clock.

TikTok made a fortune with fast-paced scrolling video. And now Facebook — once a place to connect with family and friends — is imitating it. So long, Granny, hello Reels. Twitter has done the same. And, of course, Instagram, YouTube, and everybody else trying to get rich on social media.

Gioia is doing more than decrying the rise of social media. He recognizes that all media exists within a competitive environment for our time, but the playing field is far from even. While “slow culture” media like TV, movies, books, and albums want our attention, the “Dopamine culture” of TikTok, Reels, and gambling aims for addiction.

The tech CEOs know this is harmful, but they do it anyway. A whistleblower released internal documents showing how Instagram use leads to depression, anxiety, and suicidal thoughts. Mark Zuckerberg was told all the disturbing details. He doesn’t care. The CEOs all know the score. The more their tech gets used, the worse all the psychic metrics get. […]

Instead of movies, users get served up an endless sequence of 15-second videos. Instead of symphonies, listeners hear bite-sized melodies, usually accompanied by one of these tiny videos — just enough for a dopamine hit, and no more. This is the new culture. And its most striking feature is the absence of Culture (with a capital C) or even mindless entertainment — both get replaced by compulsive activity.

Perhaps there’s a reason why, for decades now, companies have essentially been burning money trying to convince people to wear VR headsets. Hotel California, anyone? We might laugh and call it all doomscrolling, insisting (like many an addict) that there isn’t anything wrong. But in the spirit of Lent, just see what happens if you try and kick the habit. You’ll probably find that your humanity and willpower are more frail than you think.

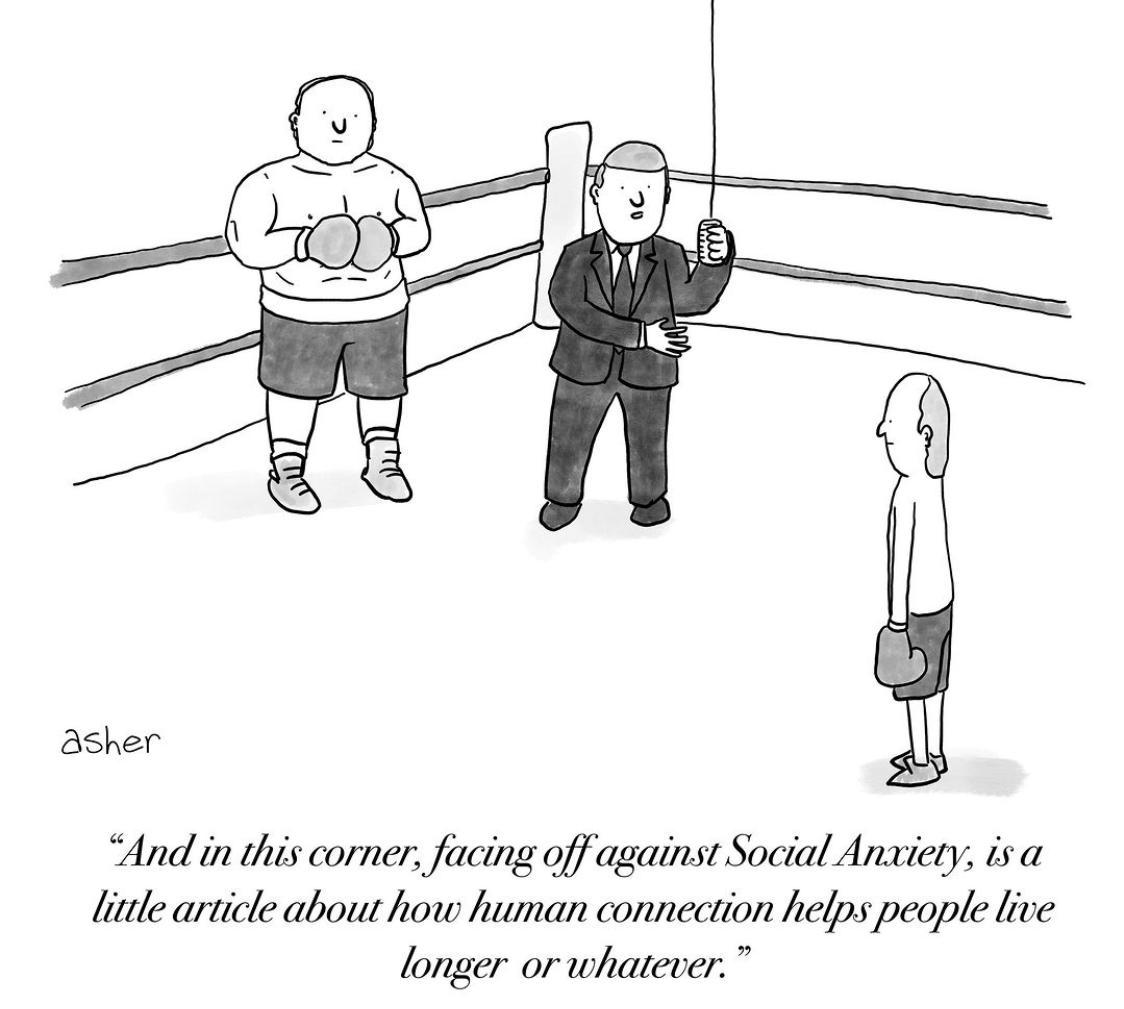

2. Gioia may be a bit alarmist (or maybe not!), but he’s certainly not alone in thinking we’re moving toward dystopia. But maybe all the doom and gloom does more harm than good? That’s at least the argument of David Brooks’s latest in the Atlantic. Because while many believe that if “your analysis is not apocalyptic, you’re naive, lacking in moral urgency, complicit with the status quo,” the cumulative effect of such a doom loop makes it more difficult to actually see the world (and ourselves) for what it is:

Today’s communal culture is based on a shared belief that society is broken, systems are rotten, the game is rigged, injustice prevails, the venal elites are out to get us; we find solidarity and meaning in resisting their oppression together. Again, there is a right-wing version (Donald Trump’s “I am your retribution”) and a left-wing version (the intersectional community of oppressed groups), but what they share is an us-versus-them Manichaeism. The culture war gives life shape and meaning. […]

I can see why, in a lonely world, people would embrace the community that collective negativity offers. As the New York Times columnist David French has noted, Trump rallies are filled with rage, but they are also characterized by a festive atmosphere, a sense of mutual belonging; immigrants might be poisoning America’s blood, but we’re having fun singing “Y.M.C.A.” together.

Being negative also helps you appear smart. In a classic 1983 study by the psychologist Teresa Amabile, authors of scathingly negative book reviews were perceived as more intelligent than the authors of positive reviews. Intellectually insecure people tend to be negative because they think it displays their brainpower.

Believing in vicious conspiracy theories can also boost your self-esteem: You are the superior mind who sees beneath the surface into the hidden realms where evil cabals really run the world. You have true knowledge of how the world works, which the masses are too naive to see. Conspiracy theories put you in the role of the truth-telling hero. Paranoia is the opiate of those who fear they may be insignificant.

The problem is that if you mess around with negative emotions, negative emotions will mess around with you, eventually taking over your life. Focusing on the negative inflates negativity. As John Tierney and Roy F. Baumeister note in their book The Power of Bad, if you interpret the world through the lens of collective trauma, you may become overwhelmed by self-perpetuating waves of fear, anger, and hate. You’re likely to fall into a neurotic spiral, in which you become more likely to perceive events as negative, which makes you feel terrible, which makes you more alert to threats, which makes you perceive even more negative events, and on and on. Moreover, negativity is extremely contagious. When people around us are pessimistic, indignant, and rageful, we’re soon likely to become that way too. This is how today’s culture has produced mass neuroticism.

In theological terms, this spiral of negativity reflects our insatiable need for righteousness, no matter how many scapegoats we sacrifice along the way. Manichean Us vs. Them solidarity only works if “we” are righteous and “they” are not. The world, however, is much more like a hospital, than the black and white pieces of a chessboard.

3. Is there a way beyond outrage? Brooks catastrophizes about how we catastrophize (the irony … ), but doesn’t offer much by way of a clear solution. For that, we turn to Asha French’s article on the recent movie, The Book of Clarence, which is both movie review and a wider reflection on her brother’s tragic death. Raised in a redlined Louisville neighborhood inundated with toxic pollution, he developed a heart condition that would eventually take his life. Watching Clarence and thinking of her brother, French remarked as the credits rolled:

“I liked the movie. Mine is a critique of the gospel,” I said. “Give me a gospel where the Romans die!”

French’s honest declaration pushed her to the writings of 20th century theologian Howard Thurman and his book Jesus and the Disinherited. Thurman’s Grandmother was a slave, but his gospel was anything but a call to slaughter the Romans.

What would Thurman say about the short distance between his grandmother’s and my brother’s vulnerability to racially constructed environments?

I know this: Thurman would caution against my demand for a gospel based on some “fundamental sense of justice” that leaves dead Romans in its wake. He would recognize hatred in this wish. “Hatred, in the mind and spirit of the disinherited,” Thurman writes, “is born out of great bitterness that is made possible by sustained resentment which is bottled up until it distills an essence of vitality, giving to the individual in whom this is happening a radical and fundamental basis for self-realization.” For Thurman, hatred is the real threat of occupation because it disguises itself as common sense and self-protection, then spreads through the disinherited as the cancer it becomes. Chemical warfare is just one tactic used against bodies like mine in this country. Thurman prioritizes a more fragile site of subjection: the soul. […] “Hatred,” Thurman reminds me, “tends to dry up the springs of creative thought in the life of the hater, so that his resourcefulness becomes completely focused on the negative aspects of his environment.”

Thurman finds in Jesus’ teaching to love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you (Mt 5:44) a way to endure in a world of injustice and not be consumed by hate. Such a love, he believed, is the wellspring of hope. For French, her own hated of racist city planners had pulled her away from remembering her brother. Thinking of him, she ends her article with hope and joy: “I feel my brother nudging me now — away from those pages, toward a new story about a life too expansive to end at the body’s last breath.”

4. Sticking with the injustice theme for a bit, in Christianity Today Russell Moore profiled the recently killed Russian dissident, Alexei Navalny, who was given the opportunity at his 2021 trial to have a “last word” before being escorted to prison. To the judge, courtroom and all those might hear him after he was gone, Navalny chose this opportunity to speak frankly of his Christian faith as the source of his perseverance.

If you want I’ll talk to you about God and salvation, I’ll turn up the volume of heartbreak to the maximum, so to speak. The fact is that I am a Christian, which usually rather sets me up as an example for constant ridicule in the Anti-Corruption Foundation, because mostly our people are atheists and I was once quite a militant atheist myself. But now I am a believer, and that helps me a lot in my activities, because everything becomes much, much easier. I think about things less. There are fewer dilemmas in my life, because there is a book in which, in general, it is more or less clearly written what action to take in every situation. It’s not always easy to follow this book, of course, but I am actually trying. And so, as I said, it’s easier for me, probably, than for many others, to engage in politics.

‘Blessed are those who hunger and thirst for righteousness, for they will be satisfied’ [Mt 5:6] It’s not that I’m great, but I’ve always thought that this particular commandment is more or less an instruction to activity. And so, while certainly not really enjoying the place where I am, I have no regrets about coming back or about what I’m doing. It’s fine, because I did the right thing. On the contrary, I feel a real kind of satisfaction, because at some difficult moment I did as required by the instructions and did not betray the commandment. For a modern person this whole commandment — ‘blessed,’ ‘thirsty,’ ‘hungry for righteousness,’ ‘for they shall be satisfied’ — it sounds, of course, very pompous, sounds a little strange, to be honest. Well, people who say such things are supposed, frankly speaking, to look crazy.

Navalny’s words here are probably a bit off the cuff, but it’s worth teasing out their logic. Though their simplicity could remind some of Shia LaBeouf’s “Just do it” motivational speech, they are patently not motivated by anything close to self-betterment, human flourishing, or even what good it might accomplish. He’s just doing what he’s told, no matter how high the cost.

5. Which leads me to this next article by theologian Paul Griffiths in the Lamp Magazine, where he scrutinizes the whole idea of “human flourishing.” Perhaps you haven’t noticed, but everyone nowadays is interested in talking about human flourishing. When philosophers, psychologists, social scientists, and theologian deign to write self-help, they talk about human flourishing. For such writers, humans are not unlike a flower that can only thrive when placed in the right conditions for growth. The question of “how shall I live?” becomes one of self-optimized utility.

This way of talking about what is good for us brings with it unanticipated, unintended, and often invisible damage. It malforms our imaginations by leading us to see what we do and what is done to us in terms of a dualism which is often crude: a sharp division between damage, which detracts from our flourishing, and repair, which supports it. The many particular patterns, events, and undertakings apparent in human lives are then allotted to just one of the two categories. If the former, they are to be removed or minimized wherever possible. If the latter, they are to be sought and nurtured wherever possible. More repair, more flourishing; more damage, less flourishing. The task is to place what we do and what is done to us in one category or the other, and act accordingly.

But something is nevertheless missing here … It is that loss, lack, and damage are intrinsic to the existence of human persons as we now are (Catholics will say since the Fall). They are a proper part of our floruit. And while there is in them that which typically does — and certainly should — prompt lament and regret, this does not suggest, and much less entail, that the parts of life in which we are not fully functioning adults, proper humans, as the floruit picture would have us think, or in which we undergo loss of capacity, have nothing in them other than lack. Damage, flourishing’s apparent opposite, may have contributions of its own to make to what it appears on its face to contradict. It may provide its own characteristic adornments. […]

Death is what gives a human life shape and texture, and provides it most of the meaning it has. Is death regrettable, lamentable, dreadful? Certainly. Is it only that, only to be seen, considered, and responded to as that? Certainly not. It is also an ornament. Advocates of human flourishing are unlikely to look at the contributions death — mortality — makes to being a human person, and even if those contributions come briefly into view, they will appear on the margins and will be further marginalized as soon as practicable. […]

Discerning which [possibilities in life] effect damage and which repair, whether for players or audience or both, is a more complex and more interesting task than the floruit picture allows. Doing it well permits the thought that infants, the aged, and the sick may effect repair by showing aspects of what it is to be a person properly productive of delight and admiration in themselves, and not merely as preparations for or derogations from something else. That is in part because attending to persons, rather than to members of a species, extends the range of what can appear as evidence of repair. It is also because a close look at how persons are in a fallen world, whether individually or collectively, shows that damage and repair are not as insulated from one another as the floruit picture indicates them to be. The worm is always in the bud, and it is the intimacy between worm and bud, bud and worm, seen clearly, that provides persons the only possibility we have of moving toward an unimaginable condition in which there will be no worm and, therefore, no bud.

Though he doesn’t cite the German reformer, Griffiths describes the project of human flourish in terms reminiscent of Martin Luther’s “Theology of Glory.” Human flourishing “calls evil good and good evil … Therefore he prefers: works to suffering, glory to the cross, strength to weakness, wisdom to folly, and, in general, good to evil.” In this way, the logic of human flourishing has more in common with flowers than it does actual humans.

6. On the more lighthearted side of the internet, Reductress offered up a humorous take on the bound will with their “Woman Horrified to Find Thing She Likes Is Actually Huge Trend.” And their “Why I’m Applying to Harvard After Getting ‘Genius’ in Spelling Bee” skewers those of us who have passed around our Wordle scores.

But my favorite one this week came from the Hard Times, who echoes more than a few of Jesus’ teachings in, “Man Who Experienced Ego Death Sure Loves Flaunting It“:

Local psychedelic enthusiast Sam Roscoe, 27, is reportedly seizing every given opportunity to flaunt his ego death as an exercise in parading his newfound humility, confirmed multiple sources tired of the subject. […]

“His ego was definitely more dead before he took the shrooms,” said Clover. “Or perhaps his ego did die, only to be immediately reincarnated as a giant flashing neon sign that follows him everywhere. I cannot stop him from talking about how enlightened and empathetic he is, and trying to convince me to drop acid with him because I need to ‘get on his spiritual level.’ All I know is that a brave soul needs to slay his ego once and for all. Just do us all a favor and put the damn thing out of its misery, for my sake.” […]

At press time, witnesses were stunned as Roscoe held a funeral for his ego, complete with fireworks, in a public park.

7. To close out this week on more of a high note, over at Covenant Justin Holcomb offers a hopeful reflection on Jesus’ words: “Come to me, all who labor and are heavy laden, and I will give you rest” (Mt 11:28):

Included in this is a gentle invitation to weary humans because human misery comes from the captivity and destructive power of sin. We all carry this curse, although the particular sins and exhaustions may take different forms. And that’s why the invitation from Jesus is to all.

We feel weary and burdened by the guilt of sins that we commit. But that’s not the only burden we carry. We’re also weary because of the sins done against us and the effects of sin in the world around us: sickness, suffering, and death.

This first Comfortable Word acknowledges the depth of human longing for good news and our need for rest. We suffer from spiritual fatigue, the most readily apparent fruit of human sinfulness, but there is good news. God favors the weak, not the spiritually proud or arrogant, but the broken. Jesus embraces the meek and the broken, the humble ones who feel swamped with heavy burdens. […]

Jesus invites us to himself. He’s not pointing us back to ourselves with advice on weariness management or techniques for rest maximization. Of course there are great techniques and advice for dealing with weariness in the here and now. Jesus is not opposed to those, but he’s addressing the deeper exhaustion we all experience. In that moment, it’s all about him and who he is, what he has done and his disposition toward us. He wants us to come to him.

To all of us who are burdened, exhausted by our sin or its effects, the first gift of the Comfortable Words is that God acknowledges our misery. We do not have to hide our longing and need for good news. Even better, God loves to respond and provide the rest we need.

Strays:

- How We Became Addicted to Therapy

- Doubt Is a Ladder, Not a Home

- AA for Legalists, aka the Church

- This week, David Zahl stopped in on the Australian podcast Upside Down People.

COMMENTS

Leave a Reply