Jam-packed AWE this week. We’ll start with some articles examining our cultural (‘little-l’) laws, then look in on theology, and then turn to culture. Oh, and Sarah Condon went on Steve Brown’s show this past week – I hear it’s incredible, and you can check it out here.

1. The divine moral law and our own cultural imperatives intersect (and diverge) in interesting ways. God’s unchanging Law dwells in our hearts, but our cultural mores are mercurial, ever-changing. You could think of God’s law and each of our cultural norm-sets du jour as Venn diagrams: our cultural morality is (1) a partial recognition of true morality (e.g., don’t kill), and it’s part (2) arbitrary cultural imperatives with no real moral content at all (e.g., thou shalt be skinny).

Right now, our cultural morality (at least that of the educated elite) seems obsessed with different types of sensitivity to difference, most of which I, personally, would firmly plant in category (1). At the same time, the fact that there’s some real moral meat there makes it dangerous, since it makes it easier to judge others with confidence. And man, those witch-hunts just keep coming. I want to disclaim any political intent here. It’s just hard to grow up in the Church and not develop an ear for when our enforcement of moral imperatives becomes harsh, unforgiving, or counterproductive. Between moral libertinism (X just doesn’t matter) and calcified moral self-righteousness (X matters, and deviants are inferior people whom we should dislike) runs a thin tightrope on which we humans can’t stay balanced for long.

The Economist this week reported on the current Pharisee-istic pole of that conundrum in the context of the Canadian conversation on cultural appropriation. An obscure literary magazine published an article defending appropriation as a sort of cross-pollination among literary traditions. Predictably, he was ousted from his job, and the aftermath was more predictable still:

The editor of Walrus, a better-known magazine, decried “political correctness, tokenism and hypersensitivity” in cultural and academic bodies. After a social-media backlash he, too, resigned. In April a gallery shut an exhibit of the work of Amanda PL, a painter inspired by the style of Norval Morriseau, an indigenous artist. . .

[Greater assertiveness from Canadian indigenous peoples] is welcome, but the silencing of other voices is not. The hounding of journalists from their jobs chills free speech. Politely, Mr Niedzviecki admits that his defence of cultural appropriation was “a bit tone deaf”. But he should not apologise too much. He provoked a debate on an important and many-sided issue. Canada prides itself on its diversity of peoples. A diversity of ideas matters, too.

These kinds of brutal backlashes have been defended on the grounds that firing someone is just responsiveness to what consumers value, but if consumers are anything like me, they tend to mount the moral high-horses far too easily. To defend personal attacks and job firings for people who reveal themselves to be, well, sinners, merely acquiesces to narrow-minded judgmentalism, which we thought we’d escaped from the 60s on. Regardless of the content of today’s set of moral norms, the form of how our culture deploys them against others – and of how those who are able to comply with them relish their role as vindicators – remains the “same as it ever was” (T. Heads).

2. In terms of the substance of moral norms, that makes a TGC report that “On Most Moral Issues Americans Are More Permissive Than Ever” sound a bit premature. Says TGC’s Joe Carter, “the overall trend clearly points toward a higher level of acceptance of a number of behaviors that the Bible clearly condemns.” I don’t want to wade into the specific “behaviors” the article mentions, but Christians on the political Left would point out that for millennia, people were highly permissive of other “behaviors that the Bible clearly condemns” – various kinds of discrimination, killings in the name of (Rage Against the Machine) this or that, etc. If we are becoming much more permissive about some things, that’s at least partially offset by the fact we’re becoming more restrictive about others.

3. The changes on our discourse, however, can be attributed to new forms of communication. On that front, the New York Times published an excellent interview with a founder of Twitter and cofounder of Blogger, Evan Williams:

“I thought once everybody could speak freely and exchange information and ideas, the world is automatically going to be a better place,” Mr. Williams says. “I was wrong about that.” . . .

The trouble with the internet, Mr. Williams says, is that it rewards extremes. Say you’re driving down the road and see a car crash. Of course you look. Everyone looks. The internet interprets behavior like this to mean everyone is asking for car crashes, so it tries to supply them. . .

Mr. Williams isn’t the only one trying to fix this mess, of course. If he and others can’t find a path forward, if they can’t solve what he calls “the architecture of content creation, distribution and monetization on the internet,” there are unsettling implications for the future of news and ideas. Maybe it will be all car crashes, all the time. Twitter already feels like that.

As a ‘Net writer, some of that dynamic just seems unavoidable. If you can see the number of Facebook shares, retweets, comments, and pageviews your work gets, it becomes difficult to not write in such a way as to make that go up. And that’s speaking as a nonprofit Christian writer, for an expressly anti-performancist organization, who’s told to never look at the stats.

For commercial writers, the situation can be far worse. Certain articles from the far-right and far-left are often chalked up to willful ignorance or personal meanness by their opponents. But more mundane pressures may actually be the culprit. In an age when veteran writers at major for-profit outlets are pressured by an embattled management to get as many pageviews as possible, content-modification becomes the norm. A hyperbole in the title, an appeal or two to the readers’ egos, and suddenly things are looking up. Baby steps toward extreme positions, sensationalism, and higher Tweetability seem a small price to pay for a larger audience, more influence, and thus – in every nonfiction writer’s mind, at least – more power to do good, to push the right ideas. Against systemic pressures like this, it takes extraordinary effort and awareness for an outlet to keep its content strong, and even when an outlet succeeds, the market may well punish them for it. Anyway, Williams continues,

In a commencement speech at the University of Nebraska this month, Mr. Williams noted that Silicon Valley has a tendency to see itself as a Prometheus, stealing fire from selfish gatekeeper gods and bestowing it on mere mortals. “What we tend to forget is that Zeus was so pissed at Prometheus that he chained him to a rock so eagles could peck out his guts for eternity,” Mr. Williams told the crowd. . .

Mr. Williams’s mistake was expecting the internet to resemble the person he saw in the mirror: serious, high-minded.

The Internet’s not nearly as cool as fire, but I do like the analogy. The assumption that humans will always be like Williams’s self-image doesn’t seem to require much refuting. If you’re like me, you can either go check your Facebook feed or Twitter trends.

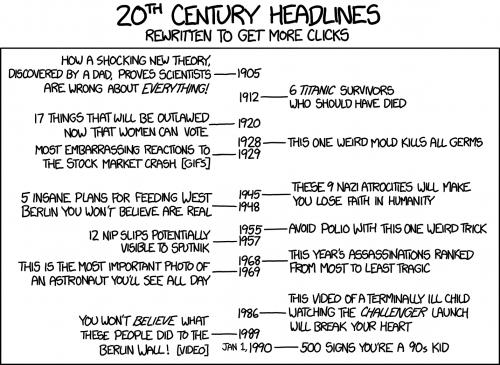

At the same time, it may be tempting to overplay some of this. For a nice look at how things maybe haven’t changed as much as we think, head over to xkcd.

4. One last piece on cultural moralities. For a law which is probably much more pervasive and insidious than any political mores, look no further than the pressure to be happy. Alan Jacobs posted a great quote on that topic. +1 for the existentialists:

Modern society, as a whole, tends toward a sort of institutional optimism, espousing Hegelian notions of history as progress and encouraging us to believe happiness is at least potentially available for all, if only we would pull together in a reasonable manner. Hence the kind of truth pessimists tell us will always be a subversive truth. All the quotations I chose from Cioran, almost at random, could be understood as rebuttals of the pieties we were brought up on: that knowledge is a vital acquisition, that we must work to help and save each other, that it is positive to be industrious and healthy, that freedom is supremely important, and so on.

Such a radical deconstruction may be alarming, yet when carried out with panache, zest, and sparkle, it nevertheless creates a moment’s exhilaration, and with it, crucially, a feeling of liberty. Reading Leopardi or Cioran or Beckett, one is being freed from the social obligation to be happy.

5. Over on Theocast, there’s an interesting parable about a smelly homeless man and a well-kept man in a suit who wander into church. The pastor’s biases about the former are important and apparent, but the pastor may be biased about the latter, too:

Because your bias and presupposition about the human condition that you picked up from the suburbs kept you from assuming the worst [about the man’s spiritual condition] in his case. It is this same perspective that allowed you to immediately assume the worst with the man in tatters. Don’t misunderstand me. You should assume the worst about the man in tatters. That’s not the issue. The issue is that you did not assume the worst about both men. Hear me. You should assume the worst about all men. If you’re not as desperate for the guy in the suit as you are the guy in rags, then your love is conditional. . .

How desperately that guy in the suit needs Jesus. Look at him! He believes his morality and church attendance saves him. Most likely, right now he’s comparing himself to that homeless guy and assuming the best about his own condition. Oh how blind he is! I’ve got to put the cross of Christ in his path. He needs to see himself as a leper and not a Republican.

It’s this nearly imperceptible presupposition about human beings coating our souls in the suburbs that’s robbed the church of its purpose and power. It’s blurred our understanding about the human condition. According to our impulse, the really lost people are lying in alleys somewhere, or in third world contexts. Evangelistic candidates don’t wear Brooks Brothers suits. Fact is, we struggle to evangelize the coats and ties because we never think to do it. With such a well-adjusted life there’s nothing to deliver him from. This is why our message sounds like a free upgrade and not a free gift of redemption.

Thought-provoking stuff. It reminds me of Kierkegaard, who spent his whole career trying to expose the desperate spiritual condition of the well-kept churchgoers in Europe of his time (he largely failed, but he did manage to lay some groundwork for the aforementioned existentialists). I wonder whether that assumption that the man in the suit is mostly okay reflects the pastor’s own bias toward thinking that a certain level of put-togetherness can, in fact, save him too. Inasmuch as the attention to the homeless man comes from a pitying or condescending attitude, the pastor’s seeing himself as the man in the suit, a person who somehow doesn’t share the spiritual plight of the homeless man. Jesus, of course, tended to go for those who couldn’t help but be acutely aware of their plight – and even they sometimes had adept defense-mechanisms which took some deconstructing. See, for instance, the story of the woman at the well, who kept trying the shift the conversation toward the more familiar ground of Jewish-Samaritan one-upmanship (“Are you then greater than our ancestor Jacob[?]”). Perhaps a well-adjusted and mostly okay life can be an immensely powerful defense-mechanism, but the spiritual plight remains the same.

For those missing their DZ fix these last couple weeks, the article also opens with a nice quote of his, transcribed from the Mockingcast.

Also in religion, Experimental Theology posted a nice short piece on how it’s sometimes more comfortable to serve people than to sit down and eat dinner with them. Ethan pointed out that it’s basically Herbert’s “Love (III)” (an amazing poem) in practice. Check out the comments for a nice discussion of Hannah Arendt, too.

For those looking for something more philosophical/academic, The Other Journal published a fascinating essay on how memory is a fundamentally constructive faculty. Proust fans, Ricoeur devotees, and those interested in storytelling will find something there to chew on.

6. For sufferers, go out there and get you a prescription of Lutherol. Posting about Lutherol, Reformational historian Alec Ryrie continues the medical metaphor. There’s some funny quips there:

The accompanying leaflet keeps the metaphor going: I particularly liked the note that the active ingredients were 90% Lutheran and 10% Reformed.

But it did leave me wondering what sort of medicine different theologies were. The title Lutherol suggests a painkiller, and I’m not sure that’s right. A painkiller would work better for Catholicism, I think. Lutheranism seems to me more like a kind of decongestant, like one of those sprays that takes instant effect. Calvinism, by contrast, is more of a purgative. Certain other Protestant groups are perhaps more psychoactive. Anglicanism is undoubtedly a depressant. Or, sometimes, a placebo. Other suggestions on a postcard please.

Ha! For more on Luther, Ingrid Rowland did a great writeup on Martin Luther for The New York Review of Books, surveying some of the books and exhibits going around on this five hundredth anniversary.

What drove Friar Martin to post his theses, however, was a spiritual insight, a realization so overwhelming that it prompted him to alter his name from Martin Luder to Martinus Eleutherius—“Martin the Free.”* The Christian hope for eternal life, he had come to believe, was a divine gift that no human being, no matter how virtuous, could ever deserve—there was no penance for sin that could truly merit divine indulgence. Salvation, therefore, was not a reward, but an outright gift from God, bestowed out of the sheer abundance of his love for his creation.

For years Friar Martin had chafed at the idea of a judgmental God who lay in wait to punish sinners. But now a phrase that had always irked him, “the righteousness of God,” struck, as he would later say, “like a thunderbolt”:

It is written, “He who through faith is righteous shall live.” There I began to understand that the righteous [person] lives by a gift of God, namely by faith. And this is the meaning: the righteousness of God is revealed by the gospel…with which the merciful God justifies us by faith…. There a totally other face of the entire Scripture showed itself to me.

Of the bevy of Luther books published this year, the author gives highest praise to Lyndal Roper‘s contribution, which is currently the one on our shelf, too.

7. In culture, The Atlantic’s Christopher Orr asks whether Disney ruined Pixar. The article answers “yes”, looking to the usual culprits: pressure to produce profits resulting in too many sequels, excessive merchandising, etc.

The painful verdict is all but indisputable: The golden era of Pixar is over. It was a 15-year run of unmatched commercial and creative excellence, beginning with Toy Story in 1995 and culminating with the extraordinary trifecta of wall-e in 2008, Up in 2009, and Toy Story 3 (yes, a sequel, but a great one) in 2010. Since then, other animation studios have made consistently better films. The stop-motion magicians at Laika have supplied such gems as Coraline and Kubo and the Two Strings. And, in a stunning reversal, Walt Disney Animation Studios—adrift at the time of its 2006 acquisition of the then-untouchable Pixar—has rebounded with such successes as Tangled, Wreck-It Ralph, Frozen, and Big Hero 6. One need only look at this year’s Oscars: Two Disney movies, Zootopia and Moana, were nominated for Best Animated Feature, and Zootopia won. Pixar’s Finding Dory was shut out altogether.

The most interesting part of the article, however, is the writer’s treatment of the theme of parent-child relations running throughout Pixar’s golden age:

The theme that the studio mined with greatest success during its first decade and a half was parenthood, whether real (Finding Nemo, The Incredibles) or implicit (Monsters, Inc., Up). Pixar’s distinctive insight into parent–child relations stood out from the start, in Toy Story, and lost none of its power in two innovative and unified sequels. . .

In their desire for the attention of 6-year-old Andy, the toys—particularly Woody the cowboy and Buzz Lightyear the spaceman—mirror children’s eagerness to capture their parents’ attention. Yet of course Andy is not a parent. He’s a child, and it’s the toys that are mostly accorded the role of grown-ups. (An astute bit of psychological realism: Andy, like most kids, uses them to pantomime adulthood.) So even as, on one level, Woody and Buzz act as children to Andy’s parent, on another they act as parents to Andy’s child: His happiness is their responsibility, and they will resort to the most-extreme measures imaginable to ensure it.

Fascinating stuff: it’s almost as if Andy’s role as a quasi-parent allows us to identify with him – as the human, and as the figure seemingly in control – while the movie’s true exploration of unconditional love comes from the otherworldly figures of the toys: spurned, forgotten, and abandoned, yet resolute in their determination to go to any lengths possible to restore their relationship with Andy, to show him love, and to secure his well-being. Sounding familiar? And the action of grace works in the opposite direction, too: when Buzz Lightyear realizes he’s not a space ranger and despairs of his own worth, he looks down at the sole of his boot and finds “Andy” written there in a permanent (!) marker. I’m plagiarizing here, of course, from Todd Brewer’s magisterial essay on the film – for more, go here.

Strays: MarketWatch (!?) posted a pretty funny listed of all the things millennials have been accused of killing. My favorite was paper napkins – apparently 86% of us are using paper towels now? The final season of Broadchurch airs in the U.S. beginning June 28 (ht CJG), and U2 goes Gospel on Jimmy Kimmel (below). Finally, we’ll be taking Monday off from the site for Memorial Day.

https://youtu.be/6ylSoAxpcKk

COMMENTS

One response to “Another Week Ends: Cultural Morality, Internet Extremism, Pastoring Suburbanites, Theologies as Medicine, More Lutheranism at 500, and Pixar on Parenting”

Leave a Reply

I like nearly everything you’ve reflected on this week. Thanks, Will! But the parable of the two church visitors fills me with conviction. (By the way, I do miss the Mockingcast. If it comes back, please know that I will be listening.)