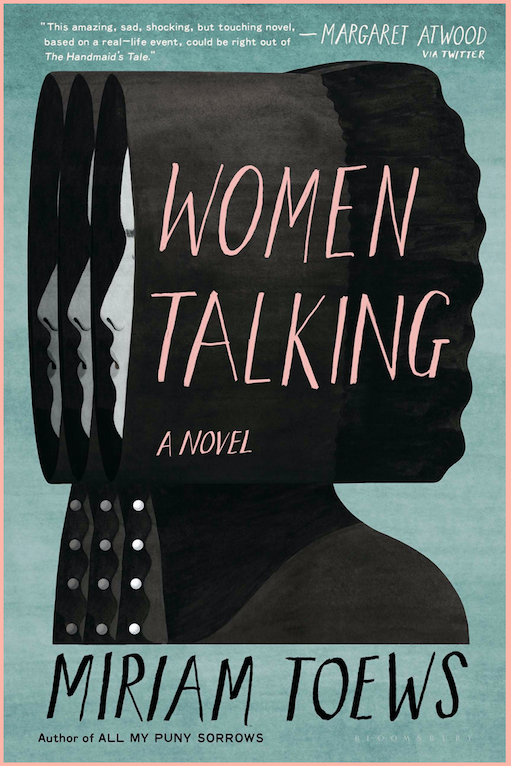

Miriam Toews (pronounced “taves”) first came to my attention in 2015 with All My Puny Sorrows, a moving novelization of her sister’s suicide; this intelligent, propulsive work tested the bounds of empathy and family loyalty. Her newest book, Women Talking, is a response to the real-life story of mass sexual assault in a remote Mennonite colony; its cover art (see below) is both elegant and ominous, evoking, at least from our current cultural imagination, The Handmaid’s Tale.

Yet even as they grapple with the heaviest themes, Toews’ books are also some of the most genuinely funny that I have encountered — not forced or satirical, just good, original humor — because, in her own words, “that is what life is like — brutal, comic, everything happening at the wrong moment.” Her characters are quirky, idiosyncratic, a mother constantly reading whodunits, a mail carrier with a rebellious spirit. “I had moved away,” says the narrator of AMPS, “…and had two kids with two different guys…as a type of social experiment. Just kidding. As a type of social failure.” The title alone — All My Puny Sorrows — gives a taste of the self-aware comedy to come; but it is taken from a beautiful, earnest Coleridge poem:

I too a sister had, an only Sister—

She lov’d me dearly, and I doted on her!

To her I pour’d forth all my puny sorrows

(As a sick Patient in his Nurse’s arms)

And of the heart those hidden maladies

That shrink asham’d from even Friendship’s eye.

Toews’ characters relate to one another all their sorrows both puny and not-so-puny. They hold one another like “sick Patients in [their] Nurse’s arms.” Her work is tragic, playful, and ultimately, as many have attested, life-affirming.

Heralded as one of her country’s foremost writers, Toews is, among Canadians, “more famous than many hockey players.” She is also a “secular Mennonite”; occasionally her characters will speak a language called Plautdietsch. In her profile on Toews for The New Yorker, Alexandra Schwartz explains:

There is a Plautdietsch term, schputting, for irreverence directed at serious or sacred things. In conversation, as in art, Toews is a schputter; she likes to puncture anything that has a whiff of pretension or self-importance about it.

Yet Toews’ novels (consistently) include a faithful character based on her mother, Elvira, who sings hymns and maintains a deep if lenient faith. Schwartz quotes Toews’ mother as saying, “Look, we have the Gospel, which means that we invite anybody and everybody in… What good is a church with locked doors?” (Reminds me of someone I know.)

*

Women Talking was released this spring in the US. The book begins after the horrifying real-life events that inspired it: in an isolated Mennonite colony, from 2005 to 2009, eight men used an animal anesthetic to knock out and subsequently rape many of the colony’s women and girls. For years, the women did not know what was happening to them. Toews explains, “Some members of the community felt the women were being made to suffer by God or Satan as punishment for their sins…still others believed everything was the result of wild female imagination.” In her preface, Toews writes, “Women Talking is both a reaction through fiction to these true-life events, and an act of female imagination.”

She imagines eight of the colony’s women gathered secretly in a hayloft to discuss what to do following these attacks. They are of all ages, grandmothers, mothers, sisters, and two teenage daughters who wear their socks rolled down because style. They settle on three options: 1) do nothing (discarded by the group almost immediately), 2) stay and fight, or 3) leave the colony. The last two options merit discussion (thus women talking) because, they wonder, how does “stay and fight” square with pacifism? How does up-and-leave square with forgiveness? The kingdom of heaven, they know, requires forgiveness. Here is a particularly thoughtful excerpt:

But is forgiveness that is coerced true forgiveness? asks Ona Friesen. And isn’t the lie of pretending to forgive with words but not with one’s heart a more grievous sin than to simply not forgive? Can’t there be a category of forgiveness that is up to God alone, a category that includes the perpetration of violence upon one’s children, an act so impossible for a parent to forgive that God, in His wisdom, would take exclusively upon Himself the responsibility for such forgiveness?

Being illiterate, they cannot read the Bible so the women improvise based on what they’ve been given. One of the matriarchs cuts a path forward, in favor of option 3. Should they stay, she says, they would “knowingly be placing ourselves in a direct collision course with violence, perpetrated by us or against us… By staying…we would be bad Mennonites. We would be sinners, according to our faith, and we would be denied entry to heaven.” Most of the women talking are very faithful and remain so throughout the book. In the words of Lily Meyer at NPR, “[Women Talking] is an indictment of authority and a defense of belief…there is no cruelty here. In the half-abandoned barn that becomes these women’s shrine, storytelling is a collective act, and religion survives only through generosity.”

Being illiterate, they cannot read the Bible so the women improvise based on what they’ve been given. One of the matriarchs cuts a path forward, in favor of option 3. Should they stay, she says, they would “knowingly be placing ourselves in a direct collision course with violence, perpetrated by us or against us… By staying…we would be bad Mennonites. We would be sinners, according to our faith, and we would be denied entry to heaven.” Most of the women talking are very faithful and remain so throughout the book. In the words of Lily Meyer at NPR, “[Women Talking] is an indictment of authority and a defense of belief…there is no cruelty here. In the half-abandoned barn that becomes these women’s shrine, storytelling is a collective act, and religion survives only through generosity.”

In an interview with the LA Review of Books, Toews reveals she originally wanted to write a story of revenge but soon realized that would not be plausible given who her characters were. Their beliefs illuminated their own way forward:

I think these women, my women in the loft, were helping me. I was trying to learn from them as I was writing, because I have a more punk attitude. I’m just filled with rage so much of the time… I was learning as I wrote. My characters couldn’t all be raging at each other nonstop. I was trying to understand, through these women, how I could think about myself as a Mennonite, where I could place myself.

Cards on the table, I am a man who read Women Talking. As such I am compelled to mention the narrator of the book, August Epp — also a man (and, notably, drawn from St. Augustine). August has been shamed by the colony for various reasons, was excommunicated at a young age, and returns as an adult but with his head hung low. He is the sole male attendee of the women’s meetings, as their minutes-taker — invited to participate by his childhood crush (whom he still loves), Ona. Women Talking is comprised of August’s notes of their meeting, plus brief interludes, windows to his own life. Guilt-ridden at a young age, August tells the following story:

In England, where I learned how to read and write, I spelled my name with rocks in a large green field so that God would find me quickly and my punishment would be complete. I also tried to spell the word “confession” with rocks from our garden fence but my mother, Monica, had noticed that the stone wall between our garden and the neighbours’ was disappearing. One day she followed me to my green field, along the narrow rut that the wheelbarrow had made in the dirt, and caught me in the act of surrendering myself to God, using the stones from the fence to signal my location, with huge letters. She sat me down on the ground and put her arms around me, and said nothing. After a while, she told me that the fence had to be put back. I asked if I could put the stones back after God had found me and punished me. I was so exhausted from anticipating punishment and I wanted to get it over with. She asked me what I thought God intended to punish me for, and I told her about…my thoughts regarding girls, about my drawings, and my desire to win in sports and be strong. How I was vain and competitive and lustful. My mother laughed then, and hugged me again and apologized for laughing. She said that I was a normal boy, I was a child of God — a loving God, in spite of what anybody said — but that the neighbours were perturbed about the disappearing fence and I would have to return the stones.

This is our narrator: a young man craving forgiveness “for being alive, for being in the world. For the arrogance and the futility of remaining alive, the ridiculousness of it, the stench of it, the unreasonableness of it.” By the end we learn (minor spoiler alert) that August was given the job of taking the minutes, not because he is a literate and upstanding man but because the women were concerned for his wellbeing. In their compassion, they gave him a job to do. They include him in their discussions, even at times asking him to weigh in. Importantly the women talking cannot read Women Talking. So, August wonders, what was the point in his taking of the minutes? “The purpose, all along,” he realizes, “was for me to take them.”

Stray notes:

- At some point, August writes a list, calls it listless, then muses on etymology: “liste, from Middle English, meaning desire. Which is also the origin of the word ‘listen.’” What a fact! Keep it in mind, people. Confirmed by the Middle English Dictionary.

- During a break, the women go outside and a truck passes by playing “California Dreamin’”. For August it becomes something of a theme song. I suppose there are a lot of reasons Toews might have chosen this song, but the longing for a better place has to rank among them.

COMMENTS

One response to “Miriam Toews Has Something to Say”

Leave a Reply

‘craving forgiveness “for being alive, for being in the world. For the arrogance and the futility of remaining alive, the ridiculousness of it, the stench of it, the unreasonableness of it.”’ !!!

also, i’m a bitch for etymologies. love that one.