The vast majority of Protestant Christians agree (1) that good works are not necessary to salvation and (2) that doing good works is good. But Protestant preaching and writing about works varies wildly. At least two reasons for that variance are different theories of how people change and different ideas about what the motive of good works should be. This will be the first of a three-part series comparing common motivators deployed in pulpits and Sunday-school classrooms with those of the New Testament epistles.

Imagine father, left haplessly solo parenting one weekend, takes his son out to the local Mexican restaurant for a solid meal and some diversion. The boy, about twelve, is failing seventh-grade biology, mainly because he’s not spending much time on homework or studying. The dad has made a couple of comments over the six weeks since the teacher notified them he was failing, and the mom has repeatedly brought it up, resulting in a series of minor clashes and a couple of true blow-ups. The dad, with some one-on-one quality time, sees an opportunity to intervene in the dispute between mother and son. He asks what the problem is in the most approachable, non-judgmental way he can, and the boy tells him he just doesn’t find biology interesting and loves Fortnite and basketball. The dad feels himself swell with earnest sympathy and wants to say:

“Your mother loves you no matter what — whether you fail chemistry or not. She works hard to put a roof over your head and provide you food and education and clothes and demands nothing in return. Her love for you doesn’t depend at all on whether you pass chemistry or not. You don’t need an A to earn her love. Instead, you study hard and apply yourself and limit your time on Fortnite out of gratitude for your mother’s unconditional love. You don’t have to do those things, but you naturally want to do them because you’re grateful for how much your mother self-sacrificially gives you without asking anything in return.”

But the dad doesn’t say it; he feels is perhaps wading into waters too deep. My personal reaction to that not-so hypothetical monologue is an immediate, visceral sense that something is off. (If you have a different reaction, would love to hear it in the comments.) It’s difficult to put my finger on it, but a couple of thoughts on why something feels off:

First, a mother’s unconditional love for a child is as high and sacred a thing as exists in ordinary human life, and there is something distasteful about using it as a tool for better grades. More than that, the child’s sense of that love is so fundamental to his psyche that it is a constitutive part of his identity. And the child is vulnerable, impressionable; a slightly careless comment might damage that sense. Even a careful and well-intentioned comment might be taken the wrong way and unintentionally wound. It just doesn’t seem worth playing around with that for the sake of grades.

That’s why, when we tell our children we love them, we rarely add to it. When I tell my son I love him, I never say, “I love you so, so much. Unconditionally, whether you share or not. Out of gratitude for that love, you might naturally want to share more — just a thought. Goodnight.” Most of us, I suspect, would be terrified that the second thought would taint the first, no matter how much we prefaced it with unconditional love. And if the second thought tainted the first — even 1% — the damage would not be worth it. It’s too sacred and fragile a thing to play around with, so we let our love be love and don’t add to it.

Yet we rhetorically play around with Jesus’s love all the time. Many Christian pastors, teachers, and writers, enlightened like the father in the story, don’t use threats or promises, but try to find a way to get through to their parishioners at the level of the heart. In searching for the key that will unlock the heart, those leaders intuitively sense that unconditional love is what we most desire, and Christ’s sacrifice for us “while we were still sinners” is the ultimate act of love for the loveless shown. So the leader seeking fuel for moral motivation reaches for the biggest tool in the toolbox and goes to work. If he were using his wife’s love for his son as a motivational tool for grades, he would likely approach it with fear and trembling, conscious of using such a powerful tool and trying to alter the child’s psyche at such a deep level. But using Christ’s love as a motivational tool for his congregation to volunteer more, he feels none of that fear and trembling. He simply goes to work.

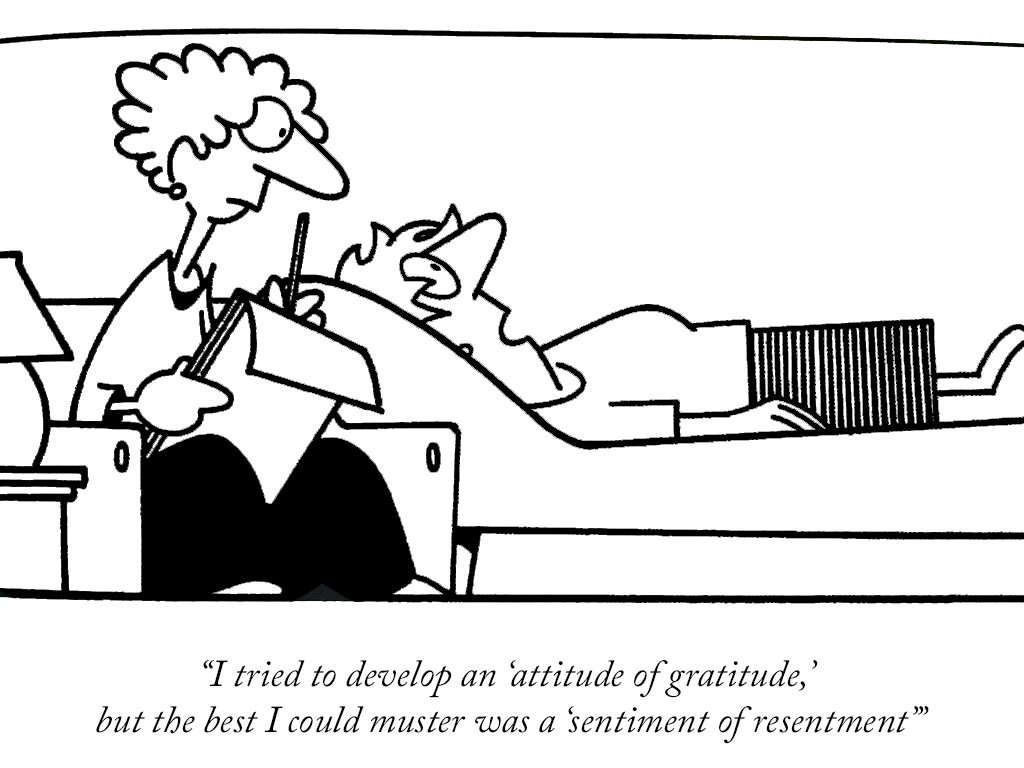

The consequences we would worry about in the Mexican-restaurant example, above, may be equally likely when telling a group of people that Jesus loves them unconditionally and they will do good things out of gratitude to him. The second part taints the first — even slightly — and muddles the listener’s precious, hard-won sense of God’s mercy. That muddling can happen, and it usually does, at least to some subset of the hearers. Many will simply miss the nuances of the gratitude message, no matter how precisely phrased, and come away with “God’s done something for you; now you need to do your part in return.” Or if they manage to actually follow the preacher through the narrow path along the cliffs of legalism, without falling off somewhere along the way, they ask themselves, “If I’m not feeling that gratitude, is something wrong with me? Do I need to bend over backwards to try to feel God’s love more?” Again, it’s meddling with deep things without the sense of awe and fragility that our father in the Mexican restaurant would dimly sense, between bites of queso, as he drew back from using Mom’s primal love as a tool to produce better Chemistry grades.

Second, gratitude to one’s mother does not naturally or automatically produce better chemistry grades. The relationship between those two things is far more attenuated and indirect. The mother’s love — and the child’s sense of that love — is crucial for their well-being, and most of us believe that nurturing that sense will help the child’s well-being. But that happens over years and years, in fits and starts, and predicting the fruit of that is an absurd task. A child’s sense of his parent’s love is just one factor in well-being, and if that sense is nurtured strongly and everything else goes just right, the child might be an A Chemistry student (or an F student but an acclaimed unicyclist, or an average farmer who’s a good father to his own children). The fruits are impossible to predict, and that much more impossible to engineer.

As an admittedly still green parent, the moments of greatest joy are not when you finally get your child to use their inside voice or take a bite of salad, but the spontaneous acts you never in a thousand years could have consciously elicited from them: make-believing the stuffed turtle is an island in a stormy sea, making strange food concoctions he thinks his parents will enjoy, instinctively hugging someone who’s sad, etc. The acts of a free human heart and imagination at play are where the lively and memorable and impactful things actually occur. As parents those moments are most rewarding when they are the least engineered, because they come from the heart — not from something external — and therefore are real and genuine.

Just as there’s no need to tell a plant that water should make it bear fruit, there’s probably little to be gained by telling people that grace should produce gratitude that will make them want to fly right. Either it does or it doesn’t, and most likely grace merely nourishes a person the way a parent’s love nourishes a child. So good works are probably not motivated by gratitude for salvation — at least not in any direct sense — and even if they were, telling someone that grace produces gratitude produces works will have no impact on grace’s power to produce those things. The only significant effect it can really have is the effect our father in the Mexican restaurant most fears, adding a slight yeast of conditionality to the otherwise solid dough of belovedness.

Perhaps that’s one reason the Apostle Paul, despite a good deal of moral exhortation at the end of his letters, doesn’t appeal to gratitude as the motive for good works. Like the dad at the Mexican restaurant, he lets God’s unconditional love be God’s unconditional love and the chemistry test be the chemistry test. He does not link the two too closely for fear of spoiling both.

Though the Epistles don’t mention gratitude as a motivator of works, they do of worship: “Let the message of Christ dwell among you richly as you teach and admonish one another with all wisdom through psalms, hymns, and songs from the Spirit, singing to God with gratitude in your hearts.” Col. 3:16. Like a bedtime “I love you” — full stop — to a child, God’s Word to instill a sense of belovedness in us elicits not a gratitude that motivates different behavior, but rather a nurtured child and the simple timeless response, “I love you, too.”

COMMENTS

7 responses to “The Role of Gratitude”

Leave a Reply

Powerful words.

Good stuff, Will! Looking forward to the next one!

“Full stop”. Still so hard to put on the brakes. Love you Will.

So good, Will. RIGHT on the money!

Thank you, Will, for this article. I needed to hear it.

Will, every day I must remind myself that faith is not by works. At the same time, it was John Piper who said that while Isaiah proclaims our works as filthy rags, God does produce works in us that are not filthy rags. Are those the works done out of gratitude? I honestly don’t know. Looking forward to your next article.

Love it. Eagerly awaiting the next one!