1. Holy smokes! Have you read Edward Mendelson’s “The Secret Auden” in the NY Review of Books?! If not, run don’t walk. It’s a jaw-dropping, incredibly inspiring catalog of the clandestine episodes of grace initiated by our all-time favorite Wystan–about as honest a Matthew 6:5 vibe as I’ve come across in ages. Lest these remarkable stories be dismissed as mere hagiography, Mendelson (author of the indispensable Later Auden) doesn’t lionize the great poet, instead tracing the ‘good works’ back to their root–which is not a sense of earning or credit (clearly) but of genuine humility brought on by piercing self-knowledge. That is to say, the further Auden plumbed his own fallibility and weakness (and few have plumbed more deeply), the more moved he appears to have been to acts of radical generosity and service. It’s another of those articles, in other words, that deserves a post of its own – even if (in fact, precisely because) its subject would object. Absolutely beautiful:

At times, [Auden] went out of his way to seem selfish while doing something selfless. When NBC Television was producing a broadcast of The Magic Flute for which Auden, together with Chester Kallman, had translated the libretto, he stormed into the producer’s office demanding to be paid immediately, instead of on the date specified in his contract. He waited there, making himself unpleasant, until a check finally arrived. A few weeks later, when the canceled check came back to NBC, someone noticed that he had endorsed it, “Pay to the order of Dorothy Day.” The New York City Fire Department had recently ordered Day to make costly repairs to the homeless shelter she managed for the Catholic Worker Movement, and the shelter would have been shut down had she failed to come up with the money.

At literary gatherings he made a practice of slipping away from “the gaunt and great, the famed for conversation” (as he called them in a poem) to find the least important person in the room. A letter-writer in the Times of London last year recalled one such incident:

Sixty years ago my English teacher brought me to London from my provincial grammar school for a literary conference. Understandably, she abandoned me for her friends when we arrived, and I was left to flounder. I was gauche and inept and had no idea what to do with myself. Auden must have sensed this because he approached me and said, “Everyone here is just as nervous as you are, but they are bluffing, and you must learn to bluff too.”…

[Auden] was disgusted by his early fame because he saw the mixed motives behind his image of public virtue, the gratification he felt in being idolized and admired. He felt degraded when asked to pronounce on political and moral issues about which, he reminded himself, artists had no special insight. Far from imagining that artists were superior to anyone else, he had seen in himself that artists have their own special temptations toward power and cruelty and their own special skills at masking their impulses from themselves…

By refusing to claim moral or personal authority, Auden placed himself firmly on one side of an argument that pervades the modern intellectual climate but is seldom explicitly stated, an argument about the nature of evil and those who commit it. On one side are those who, like Auden, sense the furies hidden in themselves, evils they hope never to unleash, but which, they sometimes perceive, add force to their ordinary angers and resentments, especially those angers they prefer to think are righteous. On the other side are those who can say of themselves without irony, “I am a good person,” who perceive great evils only in other, evil people whose motives and actions are entirely different from their own. This view has dangerous consequences when a party or nation, having assured itself of its inherent goodness, assumes its actions are therefore justified, even when, in the eyes of everyone else, they seem murderous and oppressive.

Auden’s sense of his divided motives was inseparable from his idiosyncratic Christianity… The book he wrote while returning in 1940 to the Anglican Communion of his childhood was titled The Double Man. It had an epigraph from Montaigne: “We are, I know not how, double in ourselves, so that what we believe we disbelieve, and cannot rid ourselves of what we condemn.” He felt obliged to reveal to his neighbor what he condemned in himself.

2. Next, Mockingbird’s favorite English Marxist, Terry Eagleton, has a new book out next month, and it sounds absolutely incredible, Culture and the Death of God. Jonathan Ree of The Guardian gave it a rave:

The book takes us on a rapid tour of the intellectual battlefields of Europe over the past 300 years, sites where, according to the received version of history, the brave soldiers of progress and rationality have triumphed time and again over a rabble of reactionary God-botherers. But these victories, according to Eagleton, were at best equivocal, and in due course they would be reversed by the cunning of history. First there were the fabled philosophers of the Enlightenment, leading the charge against priestly infamy and angels-on-a-pin theology; but none of them could envisage a world without God, even if they preferred to worship him in the guise of reason or science. Any damage they may have done to religion was repaired by the German idealists with their woolly notion of spirit, and by their followers the romantics, who reinvented God as either nature or culture. You might think that Marx made a better job of deicide, but on close examination the communist hypothesis turns out to have been a surrogate for the heavenly city. And poor old Nietzsche, for all his bluster and derring-do, ended up resurrecting Christ in the form of the Übermensch. The 20th-century modernists fell into the same trap, vainly appealing to art to plug “the gap where God has once been”, and if a few freaky postmodernists have managed to break away from religion in recent years, it was at the price of a complete denial of hope and meaning, which no one else is willing to pay. “The Almighty,” Eagleton concludes, “has proved remarkably difficult to dispose of.” Rumours of his death have been greatly exaggerated: he has now put himself “back on the agenda”, and “the irony is hard to overrate”.

I don’t know about you but to these ears, Eagleton’s denials of personal belief are getting harder and harder to swallow…! Those looking for a sense of his singular genius are encouraged to start here. On a related note, in The NY Times, Ross Douthat took issue with the same New Yorker article on atheism that rubbed us the wrong way. Certainly one of the most glaring gaffes in that piece were Adam Gopnik’s characterization of David Bentley Hart’s book, The Experience of God, which Douthat amply expounds upon here. The tastiest morsel, however, may be the closing to that post:

Gopnik’s failure to grasp that fairly elementary point — that the possible conceptions of God are not exhausted by the lightning-hurling sky-god and the mostly-irrelevant chairman of the board — suggests… how little they know of religion who mostly secularism know.

3. Some of us are counting the days, hours, minutes until The Grand Budapest Hotel hits theaters on March 7th, and in anticipation of the big day, The Wall Street Journal published a fairly interesting article “The Life Aesthetic With Wes Anderson”. Of interest to Mbirds will be the fact that Wes lists Reformation artist Hans Holbein as an influence on this one! Though my favorite line is probably the CS Lewis-like one Ralph Fiennes quips about the director, “Wes has his own unusual nostalgia for a world he was never part of but would like to be”. Also in the promotion for the film, Wes answered some questions from TIME magazine, and one particular exchange stuck out in its utter graciousness:

Interviewer: You mentioned all these other directors who influenced you. If some director 75 years from now says he’s influenced by Wes Anderson, what do you hope he means?

W. Anderson: Jeff Goldblum had a very funny comment to me. Jeff just said to me, ‘When I talk about the movie, we haven’t really discussed what message we want to get across. Is there something you want to say? Is there something I can throw in that you’re not comfortable getting out there? And when you die, God forbid, when you’re 107, what is the sentence that you want people to say: ‘As Jeff Goldblum said about him…’

I said, ‘Wow, that’s interesting. I have no idea and I would not really want to participate in that conversation — in writing that sentence — but I like the idea that you’re thinking about it and I bet it’ll be a good one.’

Check out our past coverage of all things Andersonian by clicking here.

4. Also on the movie tip, writing for The New Yorker, Richard Brody asks “Is Method Acting Destroying Actors?” He uses James Franco’s recent op-ed about Shia LaBeouf as a jumping off point for some striking thoughts on the discrepancy between the actor and their public personae. Philip Seymour Hoffman figures prominently, ht JL:

An actor’s attempted excavation of her own deepest and harshest experiences to lend them to characters adds a dimension of self-revelation (even if only to oneself), of wounds reopened and memories relived, that would make for agony in therapy. On the other hand, the effort to conceive a character as a filled-out person, with a lifetime of backstory and biographical details, becomes a submergence into another (albeit fictitious) life, an abnegation of a nearly monastic stringency. In the effort to make emotions true, to model performance on the plausible actions of life offstage or offscreen, the modern actor is often both too much and too little herself…

The actor’s sense of a lack of control… is another story altogether. The most poignant thing about acting in movies is the mediation of the camera. I wrote about this a few years ago: in theatre, an actor gives; in movies, the actor is taken from. Many of the great movie actors were minor, failed, or natural stage actors, or not actors at all (e.g., John Wayne); they became stars through the force of personality, of charisma, not through any studied technique. Some actors cultivate technique because it’s the aspect of performance that they can control—even if it’s not the part of their performance that the camera loves, and to which they owe their success. Other actors, frustrated by their lack of control, turn to politics or other outside ventures on which they can leave the marks they choose. Some, of course, become directors (and some become great ones).

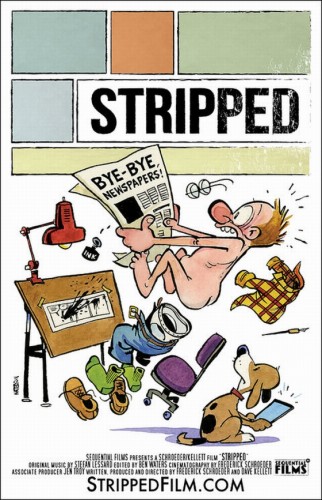

5. Probably the most exciting thing to happen this week was the unveiling of new artwork by Calvin and Hobbes creator Bill Watterson! He designed a poster for the documentary Stripped, and even recorded an interview for it, a snippet of which can be heard here:

6. TV: Other shows are apparently being broadcast (About A Boy, anyone?!), but I only have eyes for True Detective at the moment. Not that you should – it is beyond grisly. But despite the mounting pushback (some of which is particularly vapid and more illustrative of the limits of critiquing TV of this kind while it’s being aired than anything else), this series gets inside you! In my own detective work, I came across another fabulously interesting interview with writer Nic Pizzolatto where he addresses some of the nihilism expressed in the show, ht WR:

I wouldn’t want any viewers to assume we had some nihilistic agenda, or reduce Cohle to an anti-natalist or nihilist. Cohle is more complicated than that. As I’ve said recently, Cohle may claim to be a nihilist, but an observation of him reveals otherwise. Far from “nothing meaning anything” to him, it’s almost as though everything means too much to him. He’s too passionate, too acutely sensitive, and he cares too much to be labeled a successful nihilist. And in his monologues, don’t we detect a whiff of desperation akin to someone who protests too much? When Cohle speaks of the unspeakable, is it with the same illusory perspective as when Hart speaks about the importance of having rules and boundaries? Perhaps that is what Hart references when he tells Cohle in episode 3, “You sound panicked.”

That doesn’t lessen the potential validity of the ideas he expresses, and that is what I finally think is disturbing about the show so far. It’s not the serial killer that’s unsettling; television shows you far worse than that all the time. What unsettles are the aspects of being human which the show chooses to highlight. That this stuff is being delivered through actors as instantly amiable and comforting as Harrelson and McConaughey makes it doubly subversive. And then I think you’ll find, as we go forward, the show keeps subverting its own subversions.

Hmmm… I’m going to go against my better instincts and issue two predictions for these final episodes: one, Maggie and her extended family are going to play a key role, and two, the Gethsemene reference in the first episode will be extremely important. Mark my words. Also, this tumblr is pretty clever.

7. In humor, The Onion headline-of-the-week has to be the profanity-laced, oh-so-true “Friend Attempting To Provide Comfort Has No %&$#-ing Clue What She’s Talking About”, and Mental Floss posted a pretty amusing list of “4 Russian Travel Tips for Visiting America”. Number four especially:

US etiquette also forbids lamenting the troubles of life, or sharing your problems with others. Sharing in this country can only be positive emotions—sorrows and frustrations are impermissible. In the US you only complain to acquaintances in the most extreme cases. Serious problems are for close friends and relatives only.

8. To mark the release of Son of God, The AV Club devoted their Watch This column to their favorite religious films, and while the commentary may reveal some not-terribly-surprising limitations in theological learning, the movies they’ve highlighted so far are excellent, chief among them being Albert Brooks’ Defending Your Life, Pier Paulo Pasolini’s The Gospel According to St. Matthew, and Roberto Rossellini’s The Flowers of St. Francis. All must-watches. Sidenote: in the write-up for St. Matthew, Pasolini is mistakenly and somewhat sensationally referred to as an atheist. He was no Christian, but to call where he ended up (or how he got there) atheism is a major stretch.

9. Finally, a heartfelt thanks to everyone who helped put on the Liberate Conference last week! Tullian’s keynote went live today, and there are some truly great one-liners in there (brother):

Liberate 2014 – Tullian Tchividjian from Coral Ridge | LIBERATE on Vimeo.

P.S. The bulk of the Mbird magazines went out on Monday and should be hitting mailboxes as we speak! To subscribe, be sure to visit the magazine micro-site.

COMMENTS

Leave a Reply