At the end of August, I shared a quote from sociologist Zygmunt Bauman in which he described social media networks and various communities in our day as reflections of the individual. That is, we contemporary Americans tend to seek out communities and people that help express our inner selves more visibly to the wider world. Like my new iPhone 7, J.Crew shirt, and selvedge denim jeans reveal something about their owner, so in much the same way are my networks and circle of friends an extension of my inner ego. And if Bauman is correct in that observation, then might it be that God is also totally me-sized?

At the end of August, I shared a quote from sociologist Zygmunt Bauman in which he described social media networks and various communities in our day as reflections of the individual. That is, we contemporary Americans tend to seek out communities and people that help express our inner selves more visibly to the wider world. Like my new iPhone 7, J.Crew shirt, and selvedge denim jeans reveal something about their owner, so in much the same way are my networks and circle of friends an extension of my inner ego. And if Bauman is correct in that observation, then might it be that God is also totally me-sized?

There is a church I pass on my way to and from work everyday, and last week I noticed they had set out a large, wooden sign that was painted with black chalkboard paint. In the center was the question “Where do you see God?”, and around that question were answers like this: my daughters, my heart, the kindness of strangers, math, the stars, nature, and the list goes on. As I sat at the red light musing the answers prompted by the question, it occurred to me that no one had written “the death and resurrection of Jesus” or even “bread and wine” (referring to the Lord’s Supper). This would have been understandable save for the fact that this is a sign belonging to a Protestant church, not to even mention its location being a public street where many non-Christians would pass it.

That nature reflects the glory of God is, of course, integral to the Christian Faith in one sense since the creation reflects the creativity and beauty of God (see Psalm 19 as just one example). It is good and right for a Christian to be awestruck by the Triune God who “upholds the universe by the word of his power” (Heb. 1:3) when gazing at the stars on a clear night. However, the Christian recognizes that this is only because God has first made himself known. Passages like Psalm 19 make sense only in the context of God’s prior revelation of himself to Israel in which this specific God relates to this people. Which God? Well, the One who rescued them from Egypt to be his people in a land that he would give them. And this confession functions similarly for Christians today. Which God? That selfsame One who got Israel out of Egypt, he has now made himself known by his Spirit in Jesus’ incarnation, death, and resurrection. It is this particular Triune God whom Christians call the Creator.

The church sign, on the other hand, illustrates something deeper going on in our very religious culture, one in which there is a lot of god-talk from all across the religious spectrum—from agnostics to Christian types to people with Eastern and New Age leanings. Postmodern folk religion, including many Protestant churches, proposes a candidate god from among a plethora of gods: a strictly simple, solitary, nameless, and unknowable being. He (or she!) remains aloof and is separated from things going on here. One’s experience of it—and we must call it “it” because this American god lacks personality—is thus contingent on one’s own culture, choices, and experiences. As for naming it, I can choose to call this god “Jesus”, while you can choose to call it “Mother” or “Buddha”. I might best experience this nameless god in the high-church liturgy of Anglo-Catholicism, while my friend may get a better connection to it hiking in the Appalachian mountains; regardless, it is primarily about establishing my individual experience of the deity that matters.

In describing our age as an “age of authenticity” filled with “expressive individualism”, Charles Taylor’s book A Secular Age has made visible what is going on in our culture:

But it is only in the era after the Second World War, that this ethic of authenticity begins to shape the outlook of society in general. Expressions like ‘do your own thing’ become current; a beer commercial of the early 70s enjoined us to ‘be yourselves in the world of today’. A simplified expressivism infiltrates everywhere. Therapies multiply which promise to help you find yourself, realize yourself, release your true self, and so on.

A few pages later, he says,

For many people today, to set aside their own path in order to conform to some external authority just doesn’t seem comprehensible as a form of spiritual life. The injunction is, in the words of a speaker at a New Age festival: ‘Only accept what rings true to your inner self.’

Nearly everything in contemporary America is tied to this mantra. What line did a new loft building in my city use for their ad just out this week? What else but “Live your Story”? From friendships to significant others to the newest products, they are here to help both you be truly you and me be more authentically me. Just so, should we not expect this to carry over to our conception of the unknowable deity of the West? Here is how the typical god-talk on the street goes: “I want my God to be…”; “I feel God is like…”; “I choose to see God this way…” Since this distant god is ultimately nameless and mute, the individual self has free choice to fill the middle space with whatever he or she pleases. Where our various names for this god finally converge, its identity is finally seen. In theologian Robert Jenson’s words, “The unique self-identity of the one God of standard religion is established by the upward convergence of an ontological pyramid…and is known by our ascent of that pyramid.”

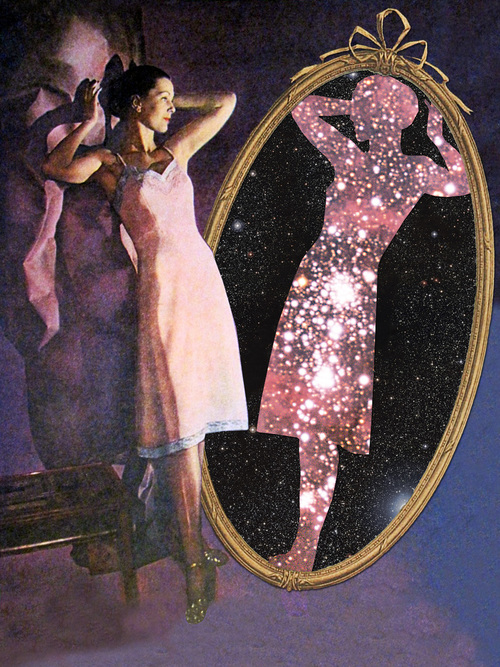

The self’s gaze brings the god of American folk religion into the light to be seen; I see, define, and name this god. When the self finally freezes upon the sight of it, whether in the stars, the anthill, or the beauty of another human being, etc., the human has finally established the identity of its god. When I finally catch sight of it, I am bedazzled by its glory and am moved to bow before it. These places where I behold this god, where I delight in its sheer power and dazzling splendor, are the resting places of how I see this god: I experience it in the flowers, but my friend catches sight of it at sundown on Carmel Beach. Thus, when I have finally given a name to it and have glimpsed my god, it turns out that the place in which I have seen it functions as a mirror. And when one looks in a mirror, it reflects back the one who is looking into it. In short, the god that bedazzles me is a mirror image of its creator, a display of my desires and longings. Like my new iPhone, it is an extension of me.

In a word, the divine is figured in the idol only indirectly, reflected according to the experience of it that is fixed by the human authority—the divine, actually experienced, is figured, however, only in the measure of the human authority that puts itself, as much as it can, to the test (Jean-Luc Marion, God without Being).

And here, is not the atheist correct? Certainly when the religious group that names this god stops assembling together, the god will finally go unheard of and should be dismissed altogether. Like all idols, it doesn’t talk back.

And here, is not the atheist correct? Certainly when the religious group that names this god stops assembling together, the god will finally go unheard of and should be dismissed altogether. Like all idols, it doesn’t talk back.

But the God of Israel cannot be melded together with the god of folk religion. In his recently transcribed lectures entitled A Theology in Outline: Can These Bones Live?, Robert Jenson compares modernity’s religion to Christianity:

This God does not ride serenely above the historical reality of the temporal world as does the god imagined by Western modernity. Modernity’s particular religion, often called Deism, believes in God but thinks that God must be immune to and uninvolved with the vicissitudes, happenings, and contingent chances that make up our history and time. The God depicted in the Old Testament does not ride serenely above the happenings of the temporal world. Israel’s God lives the history of this world together with us. And that means he has to live by and with the particularities and singularities of history. He has to enter history the same way that anyone enters history: by taking a particular place and doing particular things. And he does that the way anyone does: by identifying himself with a particular cause or movement—in fact, Israel.

The God who enters into relationship with Abraham and rescues his descendants is a talking God. Very much unlike the distant and unthreatening American deity, this particular God is the One who addresses us, who speaks to us, “who calls into existence the things that do not exist” (Rom. 4:17). He is the One who enters into our history and announces victory to the captives. In the death and resurrection of Jesus, the Triune God establishes himself as God, the One who is victorious over death itself. He is the Unnameable One who names himself and, in doing so, gives his identity-less people an identity: those who once were not but now are. The God of Israel narrates a plot line, sweeping us into his drama now made visible in Jesus Christ, that Man who was dead but who now lives to triumph.

So back to the church sign: where do you see God? Standard American religion presumes that the individual self is the central actor in his or her life movie, picking and choosing whatever definition they would like to ascribe to its god. But the God who talks, announces, threatens, and rescues, he defines himself according to the Gospel, that radically new News. And the Gospel’s God displaces me, the religious consumer, from the center. It is not my gaze that establishes him; it is his sight that establishes me. And once we have heard this word, then we may say with the psalmist: “Praise him, all you shining stars!…Let them praise the name of the LORD! For he commanded and they were created” (Ps. 148: 3b, 5).

COMMENTS

3 responses to “God as a Magnifying Mirror of Me: On American Folk Religion”

Leave a Reply

WOW–your post is absolutely mind-blowing! Thanks, Brandon, for posting it.

And for giving me good stuff to ‘chew on’.

Ha! You just confirmed what I was thinking about on my drive home tonight: the distinction is not ‘looking inward’ vs. ‘looking at the cross’… rather, it’s ‘looking inward’ vs. ‘Jesus looking at us’. Christ knowing us is the antithesis to the world’s religion. We are not in fact established by looking at Christ. We are rescued one-way by His seeing and knowing us. Our seeing God “in nature”, “in the beautiful” is in fact a very damning form of legalism. It’s an idolatry that reveals our willingness to trade being rescued and bloodily redeemed for having the agency to define and create ourselves. The reality is that everyone believes there is only one way to God (the divine): the question is the ‘what direction do you believe that one way points – self reflexively inward? Or heaven->earthward->crossward?’

Great post!

The crazy thing is, that God has already stretched Himself to be everything everybody wants!

The atheists really just want not to have to answer for their wrongs, and if they accept God’s saving forgiveness they get just that.

The addicts really just want to feel that in the end, things are going to be OK, and if they accept God’s saving forgiveness they get just that.

The deviant really just want to be loved, regardless of their proclivity, and if they accept God’s saving forgiveness they get just that.

The righteous really just want to use their knowledge of good and evil to be set apart from sinners, and when they go to Hell they get just that.

Like the good man who twists and conforms his lips, to kiss the mutilated deformed lips of a wife, who’s been so traumatized by this life, she can barely recognize her husband, but somehow she’s still overwhelmed by his loving tender touch…God has already conformed himself to meet our every want and need.