Another sampler from the Mental Health Issue! Here’s a doozie from psychologist Bonnie Poon Zahl about the meaning of ‘attachment theory’ and its implications for the ways we talk about our faith. Of course, this is only to whet your appetite…

I am a psychologist of religion. This means that I use tools from psychological science to study, empirically, the manifold expressions of religion and spirituality in human lives. I am most interested in how people understand and relate to God, and in my research I adopt the methodological naturalism that is expected in my discipline; I try to understand people’s religious and spiritual experiences by framing them in terms of natural psychological processes—the thoughts, emotions, and behaviours that together form the warp and weft of human life.

This sometimes makes Christians uncomfortable. They seem to think that I want to explain away the experiences at the core of their most cherished beliefs or strongest convictions. I find, to the contrary, that the research is not only interesting, but of real value to Christians. In what follows, I will show how this is the case—how psychology can powerfully inform both faith and practical ministry—by looking at one of the most important and well-respected psychological theories about human relationships: attachment theory.

At the popular level, attachment theory is much talked about, but also often misunderstood. If you have heard of it, it is probably through some well-meaning discussion of popular approaches to parenting children, where ‘attachment parenting’ is basically the opposite of ‘tough love’ styles like the ‘cry-it-out’ method of helping babies learn to sleep. Despite what proponents of ‘attachment parenting’ may tell you, however, attachment is not really about the benefits of breastfeeding or co-sleeping or baby-wearing for healthy child development. Rather, attachment theory explains how people learn to experience and respond to separation and distress in the context of core, close relationships from very early on in their lives. Interestingly, the effect of attachment on human relationships also seems to include our relationships with God.

*

Attachment theory was originally formulated by British psychologist John Bowlby. He wanted to understand why babies and small children respond to separation from their parents (or primary caregivers) with such apparent distress, and how such experiences of separation shape emotional and behavioural adjustment. Bowlby believed that when babies experience things that are threatening to their survival—like hunger or sickness or loud noises or distance from their parents—they reach, call out, and cry, all of which are ways to signal their needs and to restore closeness and proximity to their parents. When parents (on whom babies are quite literally completely dependent) respond sensitively and appropriately, the baby’s distress is reduced and its level of felt security is restored. But when parents do not respond, the baby continues to experience separation anxiety and distress; according to Bowlby, repeated and prolonged experiences of this kind seem to be associated with poorer emotional and behavioural adjustment.

Inspired by Bowlby’s theory, Mary Ainsworth set out to empirically study infant-parent separation with a technique she developed called the ‘Strange Situation Paradigm,’ in which infants are periodically separated from and reunited with one parent. Many hours of observations led Ainsworth to conclude that there are systematic differences in how children (in non-clinical populations) behave in these episodes of separation and reunion with their parents, and these differences or ‘styles’ can be broadly categorised into three groups: secure, anxious-avoidant, and anxious-ambivalent.

Some children (about 60 percent of them) seemed upset when their parents left, but quickly re-engaged when their parents returned; children showing this pattern were called secure. Some children (about 20 percent of them), whom Ainsworth classified as anxious-avoidant, seemed not to care about being separated from, or being reunited with, their parents; some of them even seemed to actively avoid their parents altogether, preferring instead to play alone. (Later physiological studies showed that these children are not in fact any less distressed by the separation; they just cope with this internal distress by masking it.) Other children (roughly 20 percent) were classified as anxious-ambivalent; they clung to their parents, and were extremely upset when their parents left. Even when their parents came back, they were difficult to soothe, and seemed to be angry at their parents for leaving.

Bowlby had envisioned that attachment influences relationships “from the cradle to the grave.”[1] What he meant by this is that the relational patterns developed in early childhood continue to influence other close relationships across our lifespan. This evocative thesis invited other psychologists to consider whether attachment dynamics in the same relationship changes over time, and whether attachment patterns may be observed in other close relationships, like romantic relationships and very close friendships. While there are some important distinctions between the nature of these different relationship domains, data does seem to indicate that there is a moderate degree of stability over time. Anxious-ambivalent attachment in childhood seems to correlate with more anxious attachment in romantic relationships, expressed as anxiety about the relationship partner’s proximity and the possibility of abandonment, and preoccupation with their relationship partner’s affection. On the other hand, anxious-avoidant attachment in childhood seems to correlate with avoidance of intimacy and closeness with relationship partners.

Some studies have shown that when people were asked to recall a time when their relationship partner did something that was hurtful, people who were securely attached tended to invoke more relationship-enhancing explanations, fewer relationship-threatening explanations, and they were less likely to explain their partner’s wrongdoing as reflecting something intrinsically problematic about the relationship. In contrast, people who were anxiously-attached invoked more pessimistic explanations about the relationship and the relationship partner, and more blame. Attachment style also seems to affect how a person interprets relationship scenarios that are ambiguous: people who are less securely attached are more likely to interpret ambiguous hypothetical events as reflecting hostile intentions from their partners. What all of this means is that our attachment styles can influence how we experience, remember and interpret important relational events in our lives, and we often do so in a manner that is consistent with the attachment style that we have developed during our childhood.

Overall, attachment relationships are hotbeds for some of the most powerful human emotions. As Bowlby puts it, “Many of the most intense emotions arise during the formation, the maintenance, the disruption, and the renewal of attachment relationships.” Separation seems to elicit feelings of loss, sadness, and grief, and sometimes of anger, while reunion seems to elicit joy and closeness for some, but more mixed emotions for others. These very early childhood attachment experiences, and the repeated experiences of separation and reunion, play hugely important roles in the development of our sense of who we are in relation to the people who most matter to us.

At this point, you may be wondering: does attachment theory mean that the quality of our closest relationships is determined wholly by our interactions with our parents (or that we have the power to completely mess up our children’s close relationships)? The science suggests that the answer is no: there are in fact other basic factors that have been formed even preceding attachment to parents, like our temperaments, that affect us in our close relationships. That said, our attachment relationships do form the context in which our earliest and most basic emotional and relational vocabularies are tuned.

*

But what does all this have to do with religion? For one thing, as both a Christian and a psychologist, I am struck by the profound parallels between the subject matter of attachment theory—the sequence of separation, distress, and reunion that all human beings repeatedly experience—and the Christian narrative of alienation from God because of sin, the suffering that alienation causes, and the reunion with God through his grace. Perhaps more to the point, it seems to me that attachment theory provides one lens through which we can understand how people relate to God when things go wrong in their lives. This is because, to a significant degree, our relationship to God works a lot like other close relationships in our lives, and is thus likely to be affected by the attachment patterns we developed in childhood.

Christians sometimes say that their faith is ‘a relationship, not a religion.’ There is much evidence, both anecdotal and quantitative, to suggest that a given Christian’s ‘relationship with God’ can be made sense of in attachment terms. When things go terribly wrong in our lives—when our attachment systems are activated by experiences like the loss of jobs or homes, the deaths of loved ones, serious health problems, failed relationships, or existential crises about our own identities—many Christians turn to God to restore a lost sense of felt security. The Psalmist describes God as “our refuge and strength, a very present help in trouble” (Ps 46:1), and St. Paul writes of how “neither death nor life, nor angels nor rulers, nor things present nor things to come, nor powers, nor height nor depth, nor anything else in all creation, will be able to separate us from the love of God in Christ Jesus our Lord” (Rm 8:38).

But like with the children in Ainsworth’s studies who were temporarily separated from their parents, when some Christians perceive God to be distant, unresponsive, or absent, this experience can tend to generate very strong negative feelings. Anger at God is not an uncommon response to unanswered prayer: prolonged anger at God is experienced when people need or expect God to help them in their distress, but do not feel that God is responding in the manner in which they hoped he would. Research shows that anger at God is very often accompanied by feelings of doubt about one’s relationship with God, negative interpretations of why prayers are unanswered, and even more fundamental questions about God’s goodness. Consider the example of Mother Teresa, who revealed in her personal letters the immense feelings of grief and isolation accompanying her experience of God’s silence, which lasted for more than fifty years until her death:

In the darkness… Lord, my God, who am I that you should forsake me? The child of your love—and now become as the most hated one. The one—you have thrown away as unwanted—unloved. I call, I cling, I want, and there is no one to answer… When I try to raise my thoughts to heaven, there is such convicting emptiness that those very thoughts return like sharp knives and hurt my very soul. Love—the word—it brings nothing. I am told God lives in me—and yet the reality of darkness and coldness and emptiness is so great that nothing touches my soul.

Research confirms the tendency to see God as an attachment figure and the tendency to think about one’s relational dynamics with God along the same two dimensions of human attachment: anxiety about abandonment and avoidance of intimacy. For example, some Christians, more than others, seem to be especially preoccupied with whether or not God loves them, more likely to feel angry or upset if they can’t see or sense God working in their lives, and more likely to worry about maintaining their relationship with God. These tendencies reflect a relationship with God that is characteristic of anxious attachment.

Other Christians, despite identifying as people who have relationships with God, seem to have difficulty (or seem to resist) experiencing warmth, intimacy, or closeness in this relationship. They prefer not to depend too much on God, they don’t feel a particularly deep need to be close to God even when they feel distressed, and they do not feel comfortable with emotional displays of affection. These patterns are characteristic of avoidant attachment.

Then there are those who are neither anxious nor avoidant in their relationship with God. These people, instead, seem to remain steadily connected to God through both ups and downs in their lives, and their relationship with God seems stable and integrated. These are patterns characteristic of secure attachment.

One useful way of identifying where our attachment patterns might be having a particularly strong effect on our relationship with God is to examine what we feel that God is like. Unlike purely Biblical knowledge or knowledge about God based solely on doctrine, this knowledge is deep and emotional and rooted in relational experiences with God. In my research I distinguish between these two forms of knowledge: doctrinal knowledge, on the one hand, and experiential knowledge, on the other. In spite of broad agreement among Christians on doctrinal knowledge—that God is loving, all-powerful, forgiving, and so on—Christians seem to differ from one another in the sorts of experiential knowledge that they have, and their experiential knowledge of God seems to be associated with their attachment to parents. This means that our experiential knowledge of God goes deep—the way that we experience God and what we find him to be like hangs in part on a scaffolding of relational knowledge that was given to us. What this also means is that when we discover a conflict between our doctrinal knowledge and our experiential knowledge, there is a good chance that attachment patterns are at work.

I find that knowing this helps me to have compassion (for myself and for others) when experiential knowledge resists doctrinal knowledge. When someone has a hard time believing that God really loves them, or that God will take care of them when they are in trouble, or when someone feels that God judges them for that one unforgivable thing that they did for which they are truly sorry—in these moments, our experiential knowledge stands involuntarily before our theology. Feelings of separation from God, whether or not they were “caused” by human sin or by circumstance, provide the arena in which people have to navigate potentially huge differences between their ‘head’ knowledge and their ‘heart’ knowledge. It is a space where people’s lay theodicies (their theories about God’s involvement in their suffering, and what that means about God’s nature) are made most salient.

I believe these very real, significant, and often painful experiences form a hugely important space where people’s doctrinal and experiential knowledge of God undergo change, as a result of some serious negotiations between them. For some people, these negotiations deepen and broaden their knowledge of God. God becomes bigger—perhaps more mysterious, less predictable—but ultimately no less loving. But for others, the negotiations may fail. They may find that one kind of knowledge cannot accommodate the other kind; in some cases, such crises of faith devolve into unbelief. Some people may recover, but others may not.

There is a simple but important observation that follows from this: because attachment theory is very important in shaping who we are and how we relate to other people, and because it is so strongly empirically supported, it is therefore something that people in pastoral roles would do well to integrate. If nothing else, simply realizing that a given parishioner’s unresolved anger at God over a tragedy is not just a failure of theology, but is shaped by experiences, can help birth a profound compassion for them. Too often, in situations of pastoral difficulty, Christians lead with the doctrinal and the conceptual. “If you just understood God’s grace better you would be fine!” or “Jeremiah 29! God has a plan for you!” Often, theology is not really what the problem is about, at least not exclusively. Attentiveness to psychological dimensions of religious behaviour and religious coping—attentiveness to things like attachment patterns—can be a real asset in these cases.

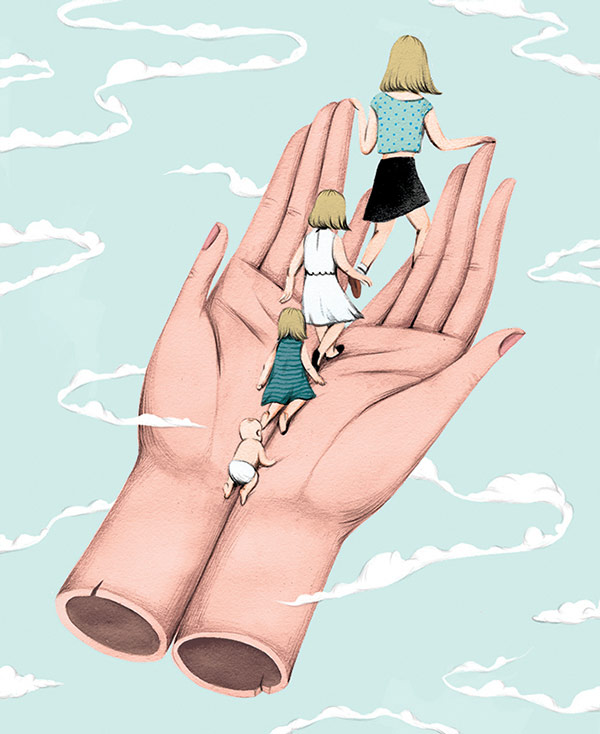

But some Christians may still be uncomfortable with all of this talk of attachment—surely God is bigger than my temperaments and my experiences as a small child? Well, yes. And no. I believe that God treats us as the human beings we are, and that includes all the biological, psychological, and cultural factors that make up who we are. This means that human psychology and human spirituality are intimately related—indeed, so much so that it is impossible to fully distinguish one from the other, in the end. Our human attachment relationships provide a framework for us to describe and understand why we, as different individuals, might relate to God in the unique and different ways that we do. Our spiritual lives are beautifully woven through the most threatening and terrifying experiences we’ve known—aloneness and helplessness—in the period of our lives when we are, quite literally, completely dependent. Just as some of us are born with a tendency towards depression or addiction, so some of us, thanks to attachment patterns, tend to relate to God in anxious ways, others with patterns of avoidance, and others in secure ways. Still, God meets us as we are.

In the end this sort of insight from psychology should not be seen as threatening to the language of faith. Phenomena like attachment are part of what it means to be a human being, created by God with a body and a mind and a personal history, and they also punctuate what it means that Jesus took on human flesh. The pattern works both ways. On the spiritual side, the Bible presents God to us as a perfect Father and caregiver, and as human beings the way we know what those words mean cannot really be fully extricated from our own patterns of attachment. And on the human side, the Incarnation shows us that God himself took on, fully, the very same kind of body and, along with it, the same kind of mind and the same kind of relationships with family and friends that give rise to human attachment patterns. There is something awesome and wonderful in how God entered the world as a baby, a baby who no doubt formed attachment relationships with his parents, and grew to have strong friendships with his disciples; and there is something terribly human in the fact that, on that Cross, he was abandoned by his closest friends and completely separated from his own Father. It means that Jesus Christ knows—not by doctrine, but by experience—the joy, love, fear, pain, anger, and sorrow that accompany our attachment relationships. It means that when we feel abandoned by God, God himself understands.

[1] Making and Breaking of Affectional Bonds, 1979.

COMMENTS

22 responses to “Attachment Theory and Your Relationship With God”

Leave a Reply

Excellent overview!

Along with the Enneagram, attachment theory has been a helpful tool in our marriage and family relationships. Milan and Kay Yerkovich use it as THE method in their marriage counseling. It is called ACPT and more info can be found at http://www.howwelove.com

Great stuff! I did a lecture a few years ago on theology and attachment theory at the Society for the Study of Psychology and Wesleyan Theology. I argued that John Wesley’s view of God’s loving presence provides what he called “assurance” to those who acknowledge it, and this is similar to attachment theory. I contrasted Wesley with John Calvin, who emphasized God’s sovereignty. For Wesley God’s loving presence provides the assurance we need to know we are loved, and we can therefore love others. For Calvin, it’s God’s control that gives security, but only to the elect. I like Wesley much better!

Thomas Jay Oord

Thomas,

I would love to know more about any situations (references) that you have and can share. I am doing my dissertation on something very similar to what you lectured on.

-Pamela

When I read my email notice of Pam’s recent post to this article, it reminded me of this book (a favorite!) because of its fascinating premise that dispensational theology was founded (and influenced by) folks who had unhealed trauma and.. serious attachment issues.

Pam, perhaps this book would be a help to you for your dissertation also?

I too would love to hear more about Thomas’ lecture on John Wesley vs Calvin and attachment theory.

WHEN THE ROLL IS CALLED — Trauma and the Soul of American Evangelicalism

By Dr. Marie T. Hoffman

“A much-needed investigation of the relationship between Dispensational theology and the lives and times of its founding fathers. . . . Their emphasis on the next life in heaven with a de-emphasis on present life in this world was a defensive strategy constructed to justify and excuse their diminishment of feelings and inattention to experienced trauma. The real shame: the untold number of evangelicals who still fail to experience the joy and healing of their life in Christ because of continued inattention to suffered and unworked-through trauma.”

–James H. Olthuis, Emeritus Professor of Philosophical Theology, Institute for Christian Studies, Toronto; Psychotherapist, Christian Counselling Services, Toronto

https://wipfand stock.com/when-the-roll-is-called.html

I was raised by foster parents for the first six months of my life, and although I was eventually returned to my family, the structure and dynamics were such that I was very distant from both parents (who were also in Christian ministry) for my entire childhood. Now in my forties, I am only just beginning to make the connections between that background and my current struggles, both in my marriage, as well as spiritually. This has been incredibly helpful. Thank you for writing it.

This was profoundly revelatory. I would love to see a follow-up showing pastors and spiritual directors how they can better incorporate attachment theory into how they coach their parishioners.

I found myself reading and re-reading several paragraphs of this article, wondering how the author could have gotten inside my head and heart. So much to consider here, thank you. And much to keep in mind as I seek to understand where others are coming from.

Agreed! A great article. More needs to be written on this. @Thomas, union with Christ is at the center of Calvin’s theology–lesser so God’s sovereignty. Calvin saw union with Christ as the “ultimate” attachment and the basis for human security. For an excellent discussion, see Julie Canliss, Calvin’s Ladder. Blessings, GLN

At last here is someone who reflects what I’ve always known and understood to be right!. As a Christian I am studying for my Level 3 ABC Course in Counselling Skills. I found your article ever so interesting, useful and excellent at explaining what my relationship (?) was like. Yes be fully aware people who work in a Pastoral Team for the Church……..yes take note……this is of extreme importance and you would be advised to follow it up!. Well done Bonnie Poon Zalh……lets see more of her writings!

Excellent, thank you. As a pastor and someone who continues to work through attachment issues of my own, I find that the avoidant and anxious categories really do play out in our relationships with God. I would challenge the statement in the final chapter though, “he was abandoned by his closest friends and completely separated from his own Father”. This is often understood to be the case because of Jesus’ words “My God, My God why have you forsaken me?” A first century Rabbi would often quote the first line of a Psalm knowing his disciples would know the rest. So in quoting the first line of Psalm 22 He meant the whole Psalm. The whole Psalm reveals that though the Psalmist FEELS abandoned, in fact he is not for His Father does not turn His face from Him. I think this is important in light of the discussion because abandonment from the Father is NOT something Jesus experienced though He did feel the pain of not being rescued from the necessary act of sacrifice He determined to endure on our behalf. There is a loving human attachment that includes allowing pain to shape us rather than stepping in to rescue-therefore stopping the growth that could happen. Thanks for the article!

This is a profound expression about life and faith. Thank you for putting into words, something that I’ve been ruminating on for 20 years! I also want to recommend How We Love as an insightful look at attachment in marriage and family. I would love to hear more!

The challenge to this article and to the topic of attachment to God is that the fundamental Doctrine of Original Sin is much more closely related to the drive mechanics and assumption of Sigmund Freud than that of Bowlby, Ainsworth, etc. So, while it would be very convenient to frame Christianity in the proximity-seeking context of attachment with the goal-correcting drive of felt security, it must be recognized that Moses chained the drive models of this faith to a less flexible dynamic with fewer tools available to manage unwanted behaviors when he set this faith in motion using his meta narratives in books such as Genesis.

I was very interested in this article until I read the author was a Christian.

I came here because I had searched for articles on the “attachment theory”. 1st time here and as an skeptical agnostic/atheist, probably last time I’ll be here.

I am continually amazed at the fact there are intelligent and learned professionals, in the field of psychology, that still embrace and support beliefs in an invisible, all-powerful deity.

Truthfully, how can it be healthy to attach oneself to a belief system that includes an invisible deity and all the things connected to the religion that surrounds that deity?

Mae

Not coming from the industry of psychology myself, I have observed that the principles of attachment theory are not limited to attachment to individuals, but also appear valid in discussing attachment to frameworks (or schemas), to symbols and symbolism, along with other complex patterns our minds have encountered. I haven’t found a lot of literature on this as of yet, but one author discussed attachment to work environments, which is a good extension of attachment theory models.

So, within the context of attachment to religion and to deities our minds believe are real, I have likened the concept to how the ozone layer protects our planet or how the skull protects the brain. Those two devices allow what they are protecting to focus less on survival needs and more in development and higher functioning, which may be why there is evidence to support the benefit of religion for many. In this case, religion can act as a defense mechanism to help manage a fear of the unknown and assist in emotional regulation which is critical to development.

On the other hand, this same defensive mechanism can prevent us from acknowledging problems that might exist within our own belief system and cause us to become defensive when challenged. This can lead to being reactive just as anyone would react when their home environment is invaded.

Protection can be good or it can lead to a lack of vigilance. There are pros and cons to each.

if I can joke a bit at your expense to make a point – your comment sounds quite “dismissive.”

The fact that there are “intelligent and learned professionals…. that still embrace and support beliefs in…..” causes you to question them rather than yourself? Interesting.

Is it possible they are aware of things of that you are not? Perhaps they have seen in their practice what much of the research supports: that such beliefs are helpful to many (with or without claims to the accuracy). It you really amazed, perhaps you should check out that research. Or perhaps really consider their experience with clients…. I could give you a list of those would attest to this kind of belief being a strength to recovery. At least one of my friends, an atheist himself, would be on that list.

Awesome article!

[…] barriers while in recovery. Research has also shown that insecure attachment styles may influence attachment security to God or a Higher Power, a foundation of the 12-steps [19]. Consider how the characteristics of each […]

Very rich insight from your presentation. I am very much informed and guided on attachment theory after reading your write up. God Bless you.

[…] https://mbird.com/psychology/attachment-theory-and-your-relationship-with-god/. This article explains how attachment theory, a psychological framework that describes how people relate to others, can also apply to how people relate to God. It explores how our early experiences with our parents or caregivers shape our expectations and feelings about God’s presence, love, and responsiveness. It also suggests some ways to heal from insecure attachment patterns and grow in a more secure and trusting relationship with God. This article is written from a Christian perspective, but it may be relevant to other faith traditions as well. […]

[…] Under it all they might feel detached and trying not to feel that, or they want to be attached and they are really trying to feel that. We are complex. And the church is an ideal, God-given setting to sort things out. But quite often it is the place where things get messed up. [Bonnie Poon Zahl on Christians and attachment theory]. […]

[…] Much like the grapes, branches and vines, God created each human with the need for connection. After Adam and Eve, there has never been a human brought into this world without connection. A baby is literally connected to the mother to sustain life during pregnancy. But the need for connection does not end after birth. I think any parent would attest to the validity of this; modern psychology has homed in on the vital importance of bonding and physical attachment in babies and children. An attachment disruption can potentially have emotional and behavioral implications in a person’s life for years. (This, of course, is a nuanced and complex concept. If you’d like to explore a little deeper into attachment and our relationship to God, this article is a good place to start. Attachment Theory and Your Relationship With God) […]

[…] online link 2) Attachment Theory and Your Relationship with God by Boonie Poon Zahl Article link 3) […]