A early version of this essay appeared in the first issue of The Mockingbird, our print quarterly. The final version is taken from A Mess of Help: From the Crucified Soul of Rock n Roll.

I couldn’t believe my eyes. If previous forays into the music and life of Elvis Presley had taught me anything, it was that the King was fundamentally surprising. Just when you thought you had him pinned down to a specific style or period or even medium, some fresh aspect of his talent would appear in your blind spot and blow your mind. I knew this in my head, but that didn’t prepare me for what I was taking in on the screen.

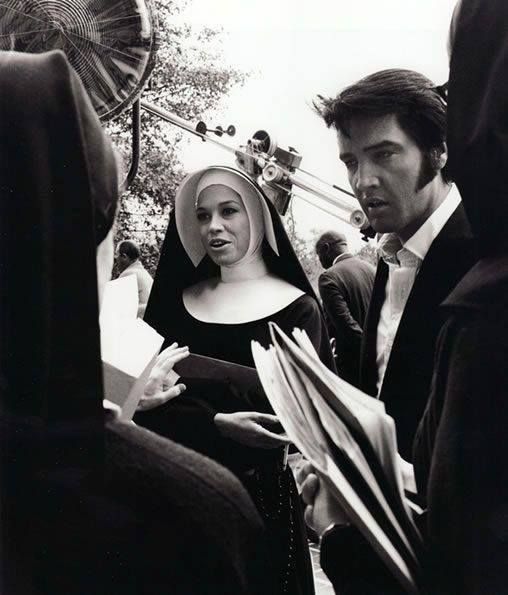

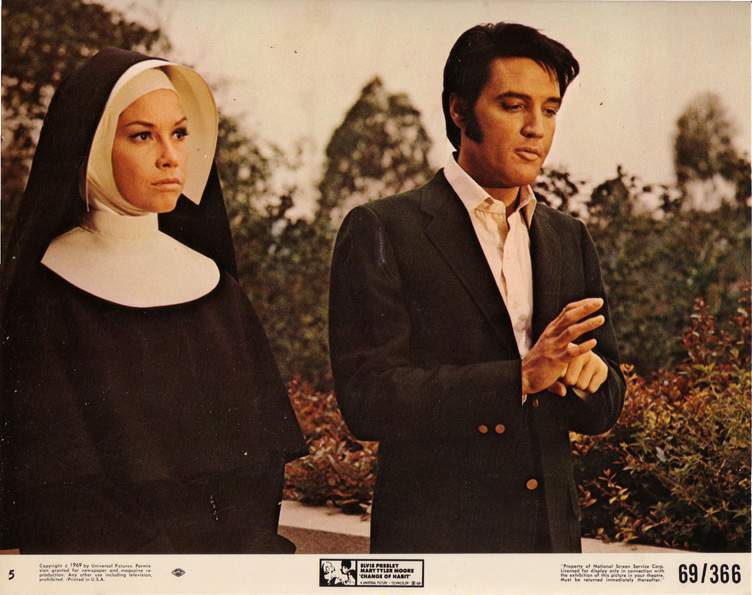

You see, I had thought there was nothing left to discover about my favorite period of his, the ‘comeback’ that started in mid-1968 and trailed off in late 1970. Yet there I was, watching the slender, sideburned master lead worship in what appeared to be a Catholic church, the camera darting from shots of the singer with guitar in hand to images of a smiling Mary Tyler Moore wearing a nun’s habit to close-ups of—of all things—the crucified Christ. And hold on—was that Darlene Love I spied dancing next to him and singing back-up? And the bassline? Vatican II was radical, but surely it didn’t allow for this degree of funk.

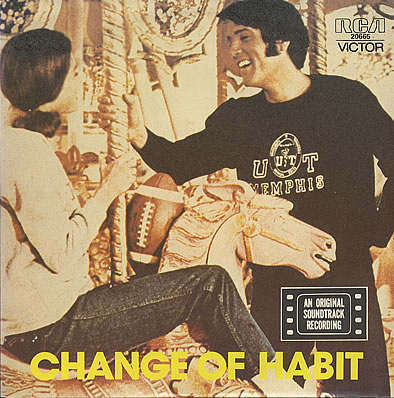

I was experiencing one of those pop culture moments that feels a bit like betrayal. How come no one had told me about this?! Weren’t there people out there who loved me, and didn’t those people know that nothing could be further up my alley, that this might even be the alley? I had stumbled on a clip from Elvis’s last dramatic film, 1969’s Change of Habit, and little did I know that my love affair with the boy from Tupelo had “only just begun” (Paul Williams).

Let me backtrack. No one disputes the magic and earth-shattering originality of Elvis Presley in the 1950s. And even those who can’t stand the schmaltz of Elvis in the 70s won’t deny that there was something iconic about his reinvention as a jump-suited Vegas crooner. The decade that people tend to ignore—comeback notwithstanding—is the 1960s. More specifically, 1961-1967, also known as his “movie period” (not entirely accurate, since he first stood in front of the camera in 1956). It’s not that Elvis was unpopular—the films raked in oodles of cash (EP was the first actor to command $1 million/picture, believe it or not)—only that there seems to be universal agreement that those years, which coincided with a break from live music performance, were something of a valley in his all-too-short professional life. The period after the films was called a ‘comeback’ for a reason.

For the Elvis fan, then, the “movie period” represents a final frontier, the place you only go once you’ve exhausted everything else. Perhaps this is why I hadn’t come across “Let Us Pray” and its video until I had been a certified Elvis lover for nigh on two decades. It had taken me that long to reach the point of desperation, where I was ready to see for myself if the movie songs were as awful as rumored. If I knew Elvis as well as I thought I did, surely there would be a handful of tracks worth hearing. His talent was irrepressible.

For the Elvis fan, then, the “movie period” represents a final frontier, the place you only go once you’ve exhausted everything else. Perhaps this is why I hadn’t come across “Let Us Pray” and its video until I had been a certified Elvis lover for nigh on two decades. It had taken me that long to reach the point of desperation, where I was ready to see for myself if the movie songs were as awful as rumored. If I knew Elvis as well as I thought I did, surely there would be a handful of tracks worth hearing. His talent was irrepressible.

I now consider my trepidation embarrassing. I had, after all, long since embraced ‘The Nazareth Principle’ as both a theological and practical truism; clearly it hadn’t reached my ears yet. The Nazareth Principle refers to the place in the New Testament where someone scoffs at Jesus by asking, “Can anything good come out of Nazareth?” (John 1:46). The implication was that Nazareth was a city in the region of Galilee which was known for its ‘mixed-blood’ and therefore suspect practice of Judaism, and because our favorite carpenter came from there, didn’t that disqualify him from being the real thing? Obviously not. In fact, the Bible sets a powerful precedent for good things—the best things even—coming from unlikely places, disdained places. Out of trouble and wounds, disappointments and closed doors, the actual breakthroughs often arrive.

If the 1960s were the Nazareth of Elvis’s career, then Change of Habit was the Nazareth of the 60s. By this point no one was even pretending to care about his movies, least of all the star himself. Could anything of value really have come out of those 30-some odd days spent distracted on a Universal backlot?

Before we go any further, it’s important to acknowledge the obvious. Elvis Presley was ridiculous. The first true global superstar, he was larger than life in every possible way, from his appetites (adoration, women, peanut butter banana sandwiches, etc.) to his delusions (karate black belt, cowboy, mystic). Of course, you cannot inspire legions of imitators without being a little absurd. Remember, this is the man who, hopped up on painkillers in December of 1970, ditched his caretakers, flew to DC, barged his way into the White House, and tried to talk Richard Nixon into deputizing him as an “special agent-at-large” in the war on drugs. There is something fabulously and un-selfconsciously comic about the man.

Yet right there alongside the silliness, there’s Elvis the artist. The singer who invented the rock n’ roll vernacular, the performer whose every stage move became archetypal, a hunk of burning instinct who could casually channel more emotion and energy into a song about shrimp (“Song of the Shrimp”) than an army of American Idols could muster for 100 “Bridge Over Troubled Water” finales. There was no genre he couldn’t own if he wanted to. Country, blues, rock, soul, lounge, funk, even folk and disco—when the monkey was on Elvis’s back, no one on Earth could touch him.

To be clear, Elvis Presley was not ridiculous, then brilliant. He was both at the same time. Which is part of what makes him so fascinating. He is someone about whom it is possible “to care and not to care” a great deal (T.S. Eliot). No wonder the man suffered so. And nowhere was this both/and, flesh/spirit, simul iustus et peccator dynamic on bolder display than in Change of Habit.

A Fool Such as I (Reconsider Baby)

There’s one other important reason why Elvis Presley deserves our attention: Elvis was a mockingbird. One of the all-time greatest, in fact.

I first remember hearing Elvis Presley’s voice when I was about eight years old, via one of the umpteen collections of his 50s hits. “Don’t Be Cruel”, “Hound Dog”, and “Heartbreak Hotel” may have long since lost the urgency and danger that made the recordings so ground-shaking when they hit the airwaves, but that doesn’t mean the songs themselves are any less appealing. Prepubescent ears don’t need help to latch on to the hooks. The problem comes after you discover The Beatles and the Beach Boys and the Stones (and all those other bands that Elvis inspired). The Sun Studio songs, as raw and exuberant as they undeniably are, can’t help but seem a little quaint—which is pretty ironic, since most of those bands found their initial success by domesticating the raw Id of early Presley.

So after a short burst of enthusiasm, teenage-dom descended, and I put Elvis aside in favor of artists who were considered to be more ‘serious’. And this is where the story takes a turn. Like pretty much everyone I knew at the time, I fell hook, line, and sinker for an aesthetic that made sharp distinctions between ‘serious’ and ‘pop’ artists, the latter of which were categorically inferior to the former. Call it an introduction to the Law of Indie Credibility, call it filtered-down punk legalism, or simply grunge pretention, but the culture in which I grew up embraced—implicitly if not explicitly—the notion that to be understood as an artist of substance, a singer or band needed to (1) write their own material, (2) play all their own instruments, (3) make big personal statements with their music (the more tortured the better), and (4) never sell out. That last one was particularly vague, and many a high school evening was spent parsing its parameters.

So after a short burst of enthusiasm, teenage-dom descended, and I put Elvis aside in favor of artists who were considered to be more ‘serious’. And this is where the story takes a turn. Like pretty much everyone I knew at the time, I fell hook, line, and sinker for an aesthetic that made sharp distinctions between ‘serious’ and ‘pop’ artists, the latter of which were categorically inferior to the former. Call it an introduction to the Law of Indie Credibility, call it filtered-down punk legalism, or simply grunge pretention, but the culture in which I grew up embraced—implicitly if not explicitly—the notion that to be understood as an artist of substance, a singer or band needed to (1) write their own material, (2) play all their own instruments, (3) make big personal statements with their music (the more tortured the better), and (4) never sell out. That last one was particularly vague, and many a high school evening was spent parsing its parameters.

There’s a lot to say about all of this, about how legitimate some of these criteria can be in theory (and how arbitrary they often are in practice), but that’s a separate essay. What’s relevant here is that Elvis Presley did not meet a single one of my prerequisites. Despite what certain rockabilly revivalists may claim, there was very little Punk about the original punk. He wasn’t a songwriter. He played passable guitar and piano but (almost) never in the studio. He may have released a couple of “message” songs (“If I Can Dream”, “In the Ghetto”), but his great subjects were love and loneliness and sex—there were rarely any “big ideas”, philosophically speaking. And as for selling out, was there ever any illusion about the man’s commercial aspirations? Elvis’s manager/taskmaster, Colonel Tom Parker, was as shrewd as they come, and Elvis was more than happy to defer to his bottom-line mentality. In fact, a strong case could be made that Parker invented modern merchandising. I digress.

Although one hesitates to use the word ‘maturity’—usually a synonym for humorlessness—I wonder if the beginning of my growing up, aesthetically at least, was the realization that ‘indie’ vs ‘pop’ or ‘serious’ vs ‘superfluous’ was largely a false dichotomy. Why did the Jackson 5 get a pass but not Take That? Was there really that much difference between Kurt Cobain and Axl Rose? It didn’t take a psychologist to see that the standards to which I was holding my favorite artists were not merely stultifying and predictable; they also had much more to do with me and my emerging identity than any artistic merit. Most of the attributes I was looking for were tacked on; they had almost nothing to do with how the music actually sounded, or the recording/performance itself.

But then there was the additional troubling fact that in the intervening years I’d experienced a conversion to Christianity. To me, the cross represented a deconstruction of identity, both musical and otherwise, that couldn’t be gotten around easily (Phil 2). In its light, my precious delineations looked petty at best. At worst, they were indicative of the inflated self-image of an original sinner—and not just because they left so little room for deviation, let alone failure or grace.

A big part of what was so freeing, so exciting, and so creatively inspiring about my newfound faith was the fact that I no longer understood myself to be responsible for generating an identity. Nor was it up to me to author the message that suddenly meant everything. The content was given. All I had to do was, by the grace of God, repeat it in a way that felt true to my experience, like the mockingbird. I was the vessel. The actor, not the director. The instrument, not the creator. Kind of like—gasp—Elvis! And contrary to my fears, I soon found that this re-ordering promoted creativity rather than limited it.

If You Don’t Come Back

I’m getting ahead of myself. Those who are mercifully unfamiliar with EP’s filmography need only know that what started out as an artistically ambitious venture (see: King Creole) soured over the course of 31 motion pictures into an inane and even degrading series of exercises in assembly-line profiteering. For the majority of the 1960s our hero was stuck, beholden to contract after contract, recording music only to support the films and rapidly losing both artistic confidence and credibility, watching from the well-appointed sidelines as his disciples in the British Invasion made the real McCoy obsolete. The film soundtracks were not without gems of course, as “Song of the Shrimp” attests (or “Viva Las Vegas” or “A Little Less Conversation” or “Long Legged Girl”), but still.

Thankfully, the intervening hand of God did not abandon EP to his own (or Colonel Parker’s) short-sighted devices. A truly miraculous series of events led to the legendary black leather jumpsuit of the televised 1968 Comeback Special, which led in turn to a musical revitalization and his first non-movie related recording sessions in years, the Memphis Sessions.

What is there to be said about the Memphis Sessions that hasn’t been said before? Not much. They’re not only as good as their reputation suggests; they were my personal bridge back to Graceland. Elvis sounds like a tiger (man) who’s just been let out of his cage, a soul reborn, singing like his life depends on it, all the unrestrained libido that had been whitewashed from his films now front and center. He chose the material himself, rehearsed the band meticulously, and worked with a reputable outside producer (Chips Moman) who refused to placate the star, thank God.

The first record released from these sessions in June 1969 was From Elvis in Memphis—far and away the King’s greatest LP. The playing crackles with electricity, the full-bodied arrangements are the best Elvis (or anyone) could ever hope for, the songs are universally top-notch, but mainly it’s the voice, the personality, the man wrapping himself around every syllable, filling the spaces with such feeling that your eardrums melt. And yet, somehow, he never overdoes it. He never sounds like he’s trying to sound like himself. From Elvis in Memphis is the crowning testimony to what Elvis was capable of when he cared, a touchstone of all that is great about American music.

Buoyed by the success of the TV special, by the end of 1969 Elvis would return to live performance. Soon “Suspicious Minds” would climb the charts, his final number one single. It was during the window between the album sessions and his first run of Vegas shows that Change of Habit was made. Distracted though he was, the film nonetheless benefited from an artist ready to take risks.

Bobbed Hair, Silk Stockings, and Reduced Rage

Change of Habit opens in a convent with a mother superior reading the Great Commission—I kid you not! The next scene, while the credits roll, we watch as three courageous nuns, one of whom is played by none other than Mary Tyler Moore, suggestively strip out of their habits and don plainclothes. The shift from reverent to titillating is extremely abrupt. Then, before we have a chance to catch our breath, the terrifically funky title song starts to play, and the three sisters make their way to what looks like Harlem, where they will serve incognito at an inner-city medical clinic. Midway through the song, after being treated to a bass solo and too many puns to count, Elvis intones: “The halls of darkness have doors that open / It’s never too late to see the light.” Indeed.

When the nuns arrive at the clinic, Dr. Elvis (in keeping with the subtlety of the rest of the film, his character is named John Carpenter) can’t hear them knocking because he’s in the midst of leading a multiracial hootenanny in his apartment (the superb “Rubberneckin’”). The good doctor J.C. finally shuffles downstairs, mistaking the nuns for knocked-up young women looking for him to perform “procedures”. After learning that they are the nurses he sent for, he proceeds to make a cringe-inducing joke about rape. (“Last two nurses who worked here got raped, one even against her will”). Before the running time has hit twenty minutes, J.C. and the gals will broach abortion, sexual assault, religion, addiction, racism, and poverty, all in the context of Christian ministry. To call the ‘social consciousness’ clunky would be generous. But there’s also something endearing and maybe even admirable here when you consider the material Elvis had been working with up to that point (e.g., Clambake).

What’s so wonderfully Elvis-like about Change of Habit is that it does not relent from there on out, neither on the silliness nor the profundity. On the former front, we get to witness the black nun being told by the neighborhood’s Black Power contingent that “she’s not black, she’s just been dipped in maple syrup.” When she warns them about the dangers of drug abuse, the leader shoots back, “Junk ain’t our bag, sister.” She then heads back to the clinic, where she and Dr. Elvis have the following interaction:

Nurse/Nun: “Doctor, do you know what it’s like to be poor? Hungry? Really frightened? To be black?”

Elvis/JC: “I’ve been all those things except black.”

Yet not all the jaw-dropping lines are race-related. The verbal sparring that takes place between the sisters and the local priest, Father Gibbons, made me laugh out loud at least four separate times. The cantankerous Father Gibbons could be considered an unfair jab at the church, were Mary Tyler Moore and her pals not such shining tributes to their faith.

Father Gibbons: “I don’t like underground nuns who wear bobbed hair and silk stockings!”

Nun: “Oh, but they’re nylon, father.”

As unintentionally funny as these lines are, there’s also something deeply serious going on. From the outset, these young women are engaged in a radical form of incarnational ministry. In order to truly reach their long-suffering neighbors, they have to leave religious trappings behind; they want to be agents of mercy, not symbols of authority—i.e., love, not judgment. The risks involved may not be as melodramatic as Change of Habit might have us believe—each of the three nuns are threatened with rape and violence—but neither are they insignificant.

In their attempts to do the Lord’s work, the well-meaning sisters encounter nothing but resistance—especially from the church. In fact, Father Gibbons, the embodiment of an inflexible old order, actively antagonizes our heroines at every turn. Instead of being applauded or encouraged, the grace these ladies show the community is mistaken for “license and wantonness” by their nosy, moralistic neighbors, and they are accused of all manner of indiscretions. Sound familiar?

Unlike its soundtrack, Change of Habit never settles into a groove, making it virtually impossible to categorize. It’s not a musical—there are only four songs, and one of them is played rather than performed—nor is it a romance, at least not in any traditional sense. There are moments of drama and moments of comedy and even action, but it doesn’t fit neatly into any genre. The closest modern touchstone would be one of Tyler Perry’s early films. Like Diary of a Mad Black Woman or Madea’s Family Reunion, Change of Habit careens wildly from one loaded situation to the next, stopping for plenty of inappropriate one-liners and wardrobe changes along the way. Thematic whiplash is putting it lightly. Presley’s final scripted film is an emotional kitchen sink.

But like those Tyler Perry films, because Change of Habit is not strictly one thing or another, it has the ring (if not the appearance) of reality. In fact, Change of Habit reaches its fever pitch in its riskiest scene, a truly am-I-really-seeing-what-I-think-I’m-seeing sequence which may also be the celluloid apotheosis of the Elvis approach. I’m referring to the part of the movie in which Elvis cures a girl of autism via Rage Reduction Therapy. The credits tell us that it was specially supervised by a Dr. Robert Zaslow.

But like those Tyler Perry films, because Change of Habit is not strictly one thing or another, it has the ring (if not the appearance) of reality. In fact, Change of Habit reaches its fever pitch in its riskiest scene, a truly am-I-really-seeing-what-I-think-I’m-seeing sequence which may also be the celluloid apotheosis of the Elvis approach. I’m referring to the part of the movie in which Elvis cures a girl of autism via Rage Reduction Therapy. The credits tell us that it was specially supervised by a Dr. Robert Zaslow.

What is Rage Reduction Therapy, you ask? We watch as Elvis holds a six year-old patient, Amanda, for what must be an entire afternoon. As she struggles against his touch, he tells her softly, “Gonna hold you ‘til you get rid of all your hate. I love you Amanda. I love you.” He encourages her to “Get as mad as you can get. Get mad at me. I love you.” The scene goes on about five times longer than anyone would expect, until finally the girl speaks… for the first time… ever. Everyone in the waiting room follows the girl’s mother and bursts into tears. I welled up as well.

Now, obviously the medical basis of this treatment is questionable, to put it mildly. One strongly suspects that it would have been viewed as absurd even at the time. Yet oddly enough, its far-fetchedness doesn’t invalidate its power. Quite the opposite. Dr. Carpenter breaks into this little girl’s mental prison, not with coercion or force, but with love and forbearance. She resists and kicks and screams, yet it has no effect on her helper’s compassionate demeanor or desire to help. His help is not contingent in any way on her cooperation. Come to find out, Dr. Carpenter’s inner-city vocation is directly related to someone saving his life in a similarly self-sacrificial way. See where I’m going with this? Even in less anachronistic settings, grace is absurd.

Half an hour of running time later, the ladies are back in their habits, and Elvis has confessed his love for Mary Tyler Moore, offering his hand in marriage. In response, she rattles off a fairly standard Hollywood line (sarcasm warning): “In marriage, you love God through one person. As a nun, I made a commitment to love God through all people.” Say whaaaat? I bet Elvis rarely got that answer in person. Cut to the church, and everyone is there, including Father Gibbons and the busybody neighbors, singing along to Elvis’s groovy benediction:

“Come praise the Lord, for He is good

Come join in love and brotherhood

We’ll hear the word and bring our gifts of bread and wine

And we’ll be blessed beneath the sign”

Believe it or not, Change of Habit ends there, but not before giving us one final gift: an unresolved conclusion. Unlike pretty much every other romance of its caliber, we don’t find out whether Mary Tyler Moore leaves the convent to marry the hip young doctor. We don’t find out if everyone lives happily ever after. Those things are left to the imagination, and to God. Like the crucifix on which the camera lingers before the credits roll, it is not neat and tidy, but it is good.

If only Elvis’s own story were equally open-ended. Alas, his revitalization was short-lived. Soon after returning to live performance, the jumpsuit caricature would codify, and while his talent never left him, the tired superstar gradually retreated behind a wall of self-medication and yes-men. “It’s hard to live up to an image”, Elvis once (under-)stated.

The fact that the comeback was not sustained does not somehow invalidate it. If anything, it underlines just how miraculous it all was. Because healing is seldom a one-time affair, regardless of what Dr. Zaslow might have us believe. “I need a miracle every day” is more like it.

Elvis proved no more exempt than any of us from the recidivism of human nature, which makes those of us who would seek to lionize him uncomfortable. We want his final note to be the “glory hallelujah” for which he was known (“The American Trilogy”). But no one’s life slopes upward indefinitely.

How comforting, then, that Elvis was not the first king to tread such a thorny descent. As grouchy old Father Gibbons might have told him, the path of grace is rarely paved with rhinestones.

True love travels down a gravel road.

COMMENTS

Leave a Reply