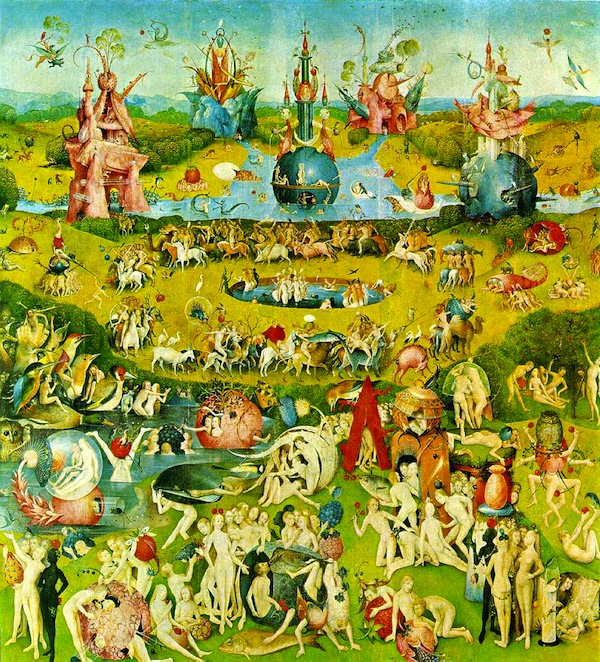

A thorough, at times exasperating, at times inspiring, and at times challenging look at science, morality and religion over on The NY Times’ Opinionator by Dutch primatologist Frans de Waal entitled “Morals Without God?”. De Waal uses Hieronymus Bosch’s painterly obsession with the pre-Fall human nature as a touchstone for his objections with what he sees as the reductionism of the Veneer Theory of human motivation (“morality is just a thin veneer over a cauldron of nasty tendencies”). Among other things, he views altruistic behavior in animals as supportive of a “bottom-up” approach to morality. But for our purposes, I felt his concluding comments on religion showed some serious insight:

According to most philosophers, we reason ourselves towards a moral position. Even if we do not invoke God, it is still a top-down process of us formulating the principles and then imposing those on human conduct. But would it be realistic to ask people to be considerate of others if we had not already a natural inclination to be so? Would it make sense to appeal to fairness and justice in the absence of powerful reactions to their absence? Imagine the cognitive burden if every decision we took needed to be vetted against handed-down principles. Instead, I am a firm believer in the Humean position that reason is the slave of the passions. We started out with moral sentiments and intuitions, which is also where we find the greatest continuity with other primates. Rather than having developed morality from scratch, we received a huge helping hand from our background as social animals.

At the same time, however, I am reluctant to call a chimpanzee a “moral being.” This is because sentiments do not suffice. We strive for a logically coherent system, and have debates about how the death penalty fits arguments for the sanctity of life, or whether an unchosen sexual orientation can be wrong. These debates are uniquely human. We have no evidence that other animals judge the appropriateness of actions that do not affect themselves. The great pioneer of morality research, the Finn Edward Westermarck, explained what makes the moral emotions special: “Moral emotions are disconnected from one’s immediate situation: they deal with good and bad at a more abstract, disinterested level.” This is what sets human morality apart: a move towards universal standards combined with an elaborate system of justification, monitoring and punishment.

At this point, religion comes in. Thin

k of the narrative support for compassion, such as the Parable of the Good Samaritan, or the challenge to fairness, such as the Parable of the Workers in the Vineyard, with its famous conclusion “The last will be first, and the first will be last.” Add to this an almost Skinnerian fondness of reward and punishment — from the virgins to be met in heaven to the hell fire that awaits sinners — and the exploitation of our desire to be “praiseworthy,” as Adam Smith called it. Humans are so sensitive to public opinion that we only need to see a picture of two eyes glued to the wall to respond with good behavior, which explains the image in some religions of an all-seeing eye to symbolize an omniscient God.

Over the past few years, we have gotten used to a strident atheism arguing that God is not great (Christopher Hitchens) or a delusion (Richard Dawkins). The new atheists call themselves “brights,” thus hinting that believers are not so bright. They urge trust in science, and want to root ethics in a naturalistic worldview.

While I do consider religious institutions and their representatives — popes, bishops, mega-preachers, ayatollahs, and rabbis — fair game for criticism, what good could come from insulting individuals who find value in religion? And more pertinently, what alternative does science have to offer? Science is not in the business of spelling out the meaning of life and even less in telling us how to live our lives. We, scientists, are good at finding out why things are the way they are, or how things work, and I do believe that biology can help us understand what kind of animals we are and why our morality looks the way it does. But to go from there to offering moral guidance seems a stretch.

Even the staunchest atheist growing up in Western society cannot avoid having absorbed the basic tenets of Christian morality. Our societies are steeped in it: everything we have accomplished over the centuries, even science, developed either hand in hand with or in opposition to religion, but never separately. It is impossible to know what morality would look like without religion. It would require a visit to a human culture that is not now and never was religious. That such cultures do not exist should give us pause.

What would happen if we were able to excise religion from society? I doubt that science and the naturalistic worldview could fill the void and become an inspiration for the good. Any framework we develop to advocate a certain moral outlook is bound to produce its own list of principles, its own prophets, and attract its own devoted followers, so that it will soon look like any old religion.

COMMENTS

3 responses to “Hieronymus Bosch, Animal Altruism and Bottom-Up Morality”

Leave a Reply

Nice. But he could push his analysis even further, beyond ethics and into epistemology: ultimately, science offers no answer for what it is to KNOW something, or what truth there is to be known. (Chapter 3 of C.S. Lewis' book *Miracles* still strikes me as being right on the money here–kudos to G.E.M. Anscombe for forcing him to polish it up.) A scientist might be perfectly content to admit that science can't address religion or ethics, as long as he or she can pretend to have a self-suffiient epistemology; if that's seen not to be the case, the gravity of our situation is more apparent.

And the gravity is that epistemology, as much as ethics, is a *given*. The tendency nowadays seems (to me, anyway, as a layman with a long-running interest in these things) to be toward a Law-driven view of science: we build the truth up ouselves, slowly, laboriously, painstakingly. Like any Law-driven approach, that takes note of some hard truths about the discovery of truth. And it turns into perfectionism–and, quickly, into ossified Pharisaical pefectionism. But the problem is that, on such a view, the race to perfection not only has no finish line; it's completely forgotten it ever had a starting line, and what that starting line was: the wholly gracious gift of the earth to man, and the wholly gracious command to cultivate it in love. We don't merely wrench scientific truth out of the world; we labor for it, yes, but in the end it's given to us. Isn't this both the end AND the means of all human labor?

But the problem is that, on such a view, the race to perfection not only has no finish line; it's completely forgotten it ever had a starting line, and what that starting line was: the wholly gracious gift of the earth to man, and the wholly gracious command to cultivate it in love. We don't merely wrench scientific truth out of the world; we labor for it, yes, but in the end it's given to us.

Beautifully written, Tracy. Thanks. Over on First Things, David Bentley Hart has a can-we-be-good-without-God? piece up himself, entitled "The Desirist's Unsatisfiable Desires," a response to atheist philosopher Joel Marks. The line I love best, and that goes to de Waal's muddled thinking in his fifth paragraph, is this: "The real question of the moral life, at least as far as philosophical “warrant” is at issue, is not whether one personally needs God in order to be good, but whether one needs God in order for the good to be good." [Emphasis mine]

Unbelievers are pretty consistent, in my experience, in asserting that morality without God is possible. Not only is it possible, they say, it is invariably better than the ethics religious people come up with. This misunderstands the nature of the argument behind Ivan Karamazov's, "Without God all things are possible." The real limiting element in a completely secular ethic is not the absence of a deity but the contingent and ultimately ad hoc nature of whatever ethical standard a non-believer comes up with. Yes, the unbeliever and the believer alike can come up with reasons why murdering the innocent is wrong and the argumentation can be sound. The atheist and the theist alike, however, are confronted with the question of whether a paradise is worth the suffering of a single child. To this Dostoevsky would point that Christ Himself bears that sacrifice with us whereas for the unbeliever if paradise is worth the suffering of a child then, well, the needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few just as the unbeliever would say they would in a religious culture.