They say you can tell a lot about a person by their favorite Beatle. Cuddly Paul, edgy John, moody George, or funny Ringo, you choose the one you either most readily identify with, or would most like to identify with. Of course, having to name only one is a dodgy practice in the first place, and not just because Paul could be edgy (“Helter Skelter”), John moody (“I’m a Loser”), George funny (“Savoy Truffle”, Life of Brian), and Ringo cuddly (“Octopus’ Garden”). I for one don’t mind pegging them as archetypes rather than people–Beatles mythology is way too fun to deny, and even the ‘lads’ themselves seem to have accepted that fact. Listen to any interview post-1975 and you’ll hear George differentiating himself “Beatle George”, John from “Beatle John”, etc. But even if you’re okay deferring to their Yellow Submarine personas, it’s much more difficult to do so when it comes to yourself. Their caricatures may remain static, but our associations with them change. My favorite Beatle has changed at least three times over the years.

A word of context: My father gave me access to his extensive record collection when I was in third grade. It was a big deal! The Beatles were my first stop (one guess who was next). He had a complete if somewhat battered collection of their LPs. Mind you, these were the American versions of the records, e.g. Something New, Yesterday and Today, Beatles’ 2nd, and like so many others before and since, their British Invasion albums inspired the musical equivalent of puppy love. As a sucker for melody, I naturally gravitated to McCartney, the most accessible and upbeat of the Fab Four. He was my favorite. Pretty sure I wore out a needle or two on “All My Loving” and “I Saw Her Standing There” alone. My interest was strongly encouraged. While other kids’ dads would quiz them about ballplayers, car makes/models, or state capitals, with mine it was Beatles’ riffs and guitar solos. He’d sing the first few notes, and I’d have to guess the song. Pretty easy when it comes to “Day Tripper”. A bit tougher with “She Said She Said” (but not that tough).

Then came the teenage years, when John Lennon predictably shot to the top of the list. “I Am The Walrus” never seemed to get old, and once I discovered “Hey Bulldog” it became (and remains) a mix-tape go-to and favorite track, Beatles or otherwise. His voice was pretty much the perfect combination of angry and sad. Plus, as we all know, there was something tragic about John which resonates with teenagers who feel misunderstood. I’m not talking about his untimely death. I’m talking about how he was the complicated, ‘troubled’ one. I’m talking about the fact that you could listen to the records, post-Rubber Soul, and hear him receding as the leader of the band (and McCartney coming forward). In the mythology of the Beatles, John is often cast as both the rebel and the victim–an incredibly potent brew for any fifteen year old. I’d go so far as to say that John Lennon is almost impossible not to idealize if you’re a sensitive young dude. The overbearing idealism and spitefulness of his post-Beatles years, as well as his fairly boring mid-70s solo work, don’t even register to those drunk on “Across the Universe”.

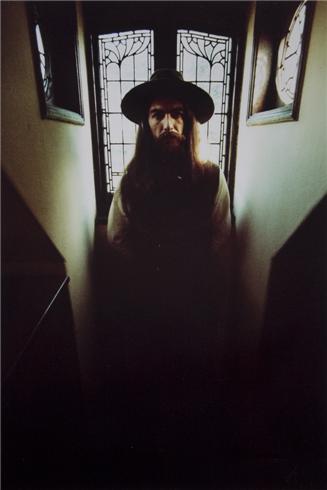

Of course, as Nirvana taught us, once those feelings of discontent subsided (a little), Lennon’s music became (a bit) less appealing. At which point I found myself, like many in my station (i.e. undergraduates), taking myself a tad seriously and imagining (!) myself as someone of depth and wisdom, even of a spiritual sort. Or maybe I just needed a little mystery to keep the music interesting. Whatever it was, I found it in the Dark Horse, George Harrison. George has it all, the melody (“Something”), the melancholy (“While My Guitar Gently Weeps”), the whimsy (“Sour Milk Sea”), even the tragic element of being the excluded third-wheel, the overlooked younger brother forced to quietly stockpile his songs. Harrison’s courage and humility in talking, incessantly, about God certainly held some appeal as well. He also did what neither Lennon or McCartney ever managed on their own: he made a masterpiece. All Things Must Pass is one of those records that swallows the listener whole with a sound so huge you completely understand why Phil Spector went nuts. Song after incredible song with nary a misplaced note or word (or army of guitars), it is a world of its own, a deeply religious record that actually sounds as majestic as the lyrical content might suggest. I’m proud to say that the foldout that came with the original vinyl, with George looking eerily like a cross between Gandalf and Jesus, hangs in my office to this day.

Of course, as Nirvana taught us, once those feelings of discontent subsided (a little), Lennon’s music became (a bit) less appealing. At which point I found myself, like many in my station (i.e. undergraduates), taking myself a tad seriously and imagining (!) myself as someone of depth and wisdom, even of a spiritual sort. Or maybe I just needed a little mystery to keep the music interesting. Whatever it was, I found it in the Dark Horse, George Harrison. George has it all, the melody (“Something”), the melancholy (“While My Guitar Gently Weeps”), the whimsy (“Sour Milk Sea”), even the tragic element of being the excluded third-wheel, the overlooked younger brother forced to quietly stockpile his songs. Harrison’s courage and humility in talking, incessantly, about God certainly held some appeal as well. He also did what neither Lennon or McCartney ever managed on their own: he made a masterpiece. All Things Must Pass is one of those records that swallows the listener whole with a sound so huge you completely understand why Phil Spector went nuts. Song after incredible song with nary a misplaced note or word (or army of guitars), it is a world of its own, a deeply religious record that actually sounds as majestic as the lyrical content might suggest. I’m proud to say that the foldout that came with the original vinyl, with George looking eerily like a cross between Gandalf and Jesus, hangs in my office to this day.

But the surprising thing about George is that he actually was pretty wise, not just in a teenage sense. He has staying power. My favorite George quote is one recounted in Scorcese’s Living in the Material World. His wife Olivia remembers George being asked, later in life, by a friend how he’d like to be remembered, and George’s response was priceless: “Why do I need to be remembered?”

What about Ringo? Well, what can I say, I never had a Ringo phase. Not unless you count the time I discovered the song “Photograph” and played it non-stop for about two weeks during my senior year of college (a Harrison co-write, for those keeping score), until my roommates issued a moratorium. But Ringo deserves a phase, if only on the strength of what he achieved with his sticks on “Rain” or “Glass Onion”, or the way he rescued pretty much all of their filmed output, including The Beatles Anthology. In fact, he is responsible for the single most profound anecdote in that documentary, about the time he quit during the making of the White Album:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MmYdxsRtVrc&w=600

Offices, families, churches–you can never be on the inside enough. Even those we think are on the inside don’t feel that way. A sermon illustration on a silver platter, you’re welcome very much (ht DJ).

This is a long and winding(!) way of admitting that, along with fifty gazillion other people, the Beatles soundtracked my coming of age–both with their music and their myth. They truly do contain multitudes, which is one of the many reasons they continue to serve as a touchstone of self-understanding for so many, including me.

But what happens when you’re one of the Beatles? When who you once were represents so much to so many that any variance–or aging–is taken as an affront? When your continued existence threatens the precious associations half the world has formed with their projection of you? How do you continue to work, let alone live, without going insane? These are key questions for those of us interested in how Demand and Righteousness and Mercy manifest themselves in everyday life. You see this dynamic to a lesser extent with actors and authors and even theologians–we don’t just want them to be a certain version of themselves, we need them to be such. We naturally over-identify with our heroes; there’s a reason they’re called “pop idols” (or icons).

If you can’t tell, I’m back to where I started, talking about Paul McCartney. He may no longer be my favorite Beatle, but that doesn’t mean I don’t find him and his solo work absolutely fascinating, from both a music lover and Mockingbird perspective (which aren’t mutually exclusive, thank God). To make it even more personal, I’d say that McCartney is not unlike that other hero of mine, Brian Wilson, in at least two ways:

1. Both men are legendary pop autodidacts, whose gifts are as undeniable as they are unexplainable. And ‘gift’ is exactly the right word. Both these guys were graced with abilities far beyond their “givens” in life, whether it be genetics, or upbringing, or IQ. I mean, Wilson may be psychologically fractured, but no one would mistake Paul McCartney for a great thinker or poet.

2. Both men have instincts that oppose their genius. Wilson’s suggestibility (and penchant for cheeeeese), McCartney’s fluffy sentimentality–these would be Achilles’ heels for lesser artists, but when it comes to these two, their talent is simply too large ever to be fully obscured. While there’s something deeply human about their penchant for self-sabotage, there’s also something deeply gracious about their inability to pull it off (completely). It’s also a big part of why they remain so interesting, even as they enter their 70s. No matter how bad a Paul McCartney or Brian Wilson record is–and they’ve both produced some real stinkers–there’s always something to recommend it. A bassline, a chord change, a backing vocal, a crunching stick of celery, etc. This makes their latter day output extremely fun for those willing to sit through the dreck to uncover the gems–because there’s always one. Even Give My Regards to Broad Street has “No More Lonely Nights.”

2. Both men have instincts that oppose their genius. Wilson’s suggestibility (and penchant for cheeeeese), McCartney’s fluffy sentimentality–these would be Achilles’ heels for lesser artists, but when it comes to these two, their talent is simply too large ever to be fully obscured. While there’s something deeply human about their penchant for self-sabotage, there’s also something deeply gracious about their inability to pull it off (completely). It’s also a big part of why they remain so interesting, even as they enter their 70s. No matter how bad a Paul McCartney or Brian Wilson record is–and they’ve both produced some real stinkers–there’s always something to recommend it. A bassline, a chord change, a backing vocal, a crunching stick of celery, etc. This makes their latter day output extremely fun for those willing to sit through the dreck to uncover the gems–because there’s always one. Even Give My Regards to Broad Street has “No More Lonely Nights.”

But I digress. Once someone embraces George Harrison, it is difficult not to look down on McCartney, to judge him as shallow and maniacally optimistic. Let the record show: I was wrong to do so. In fact, in recent years I have come to a deep respect and admiration for Macca. And not just his music. Which brings me to the occasion for this little reflection, a stunning review of McCartney’s new record New, written by Jonathan Melchior of the band Shearwater. He caught my attention when he called it “a deeply sad record” in the very first line. He goes on:

…since 1970, everything [McCartney]’s done has come with a two-word millstone attached: “former Beatle.” He’s never been able to rid himself of it. It’s not that he’s ever fallen out of fashion, or needed a “comeback”; the largest audience in the short history of popular music has consistently wanted him almost desperately, but what we really want is for him to go back to 1968 and stay there, and maybe bring us all with him. And we refuse to accept anything less than that, or as close as he can come to it.

Neil Young once handled McCartney’s dilemma beautifully, parrying a punter’s insistent requests for “Southern Man” by saying, not unkindly, “It’s a good song, but I’ll tell you what: if you go back to where you were two years ago, I’ll go back to where I was two years ago.”

Change two to 50, and you see the enormity of the task. Who could do it, even with the sincerest of efforts? Most of the uptempo numbers on New fall flat, though they’re almost all hook-encrusted and catchy in the nearly freakish way McCartney’s songs so often are. They didn’t work, for me, not because rock music is only for the young — but more that these songs so clearly illustrate that bending yourself to a demand that you remain young forever is a joyless strain that makes real freedom or adventure impossible, and there’s precious little of that here. New acknowledges this subtly, to its credit; listen, and you’ll notice that even the rockers on the album contain a lot of references to cages, locks, zoos, and calls for rescue.

…[There’s] a personality trait that seems just below the surface in him: a slightly antique (and very British) sense of duty to the role he’s been handed in life. It just happens that that role was being one of the world’s biggest pop stars. Day in, day out, whenever he appears, he seems dead-set on being, to the best of his ability, the version of himself that he believes (and not without reason) his worldwide audience wants to see. It’s hard to find a picture of him in which he’s not mugging for the camera, pointing at someone in a crowd, raising his fists above his head, giving a thumbs-up before he plays his old hits once again. But the accumulation of so many thousands of these images makes them seem weirdly opaque, an updated version of a stiff upper lip. Who is this guy? Surely he’s not really having that much fun?…

Paul McCartney has weathered his celebrity with grace for a very long time. The Beatles’ fame, five decades on, now looks like the prototype of the familiar and pervasive celebrity-mania that makes people do very strange things, and the crowds who chased the lads though A Hard Day’s Night to comic effect must have looked more like the zombies of World War Z in real life once the buzz wore off. Paul gets points just for being willing to appear in public at all, as far as I’m concerned. Almost 20 years ago, a college friend of mine spotted him on the street in New York, couldn’t resist trying to say hello, and encountered a chilly McCartney who wasn’t in the mood. “Did you follow me?” he asked, with an edge in his voice. “I don’t like being followed. Put yourself in my shoes.” My friend was crushed, but thinking about it later, realized that if he were Paul McCartney, he wouldn’t want to be followed by a fan in New York either. Just walking down the street has to be an act of some bravery for him, and he probably spends most of his time in a very fancy version of house arrest. I wonder if the recording studio isn’t one of the few places on earth where he feels safe and yet still part of the world, and if that in itself doesn’t help lure him back again.

Admittedly, some of this may be giving McCartney a bit too much credit. I’m not sure the demand is as conscious as Melchoir describes. And even if it is, are you really asking me to feel sorry for the richest man in England? Well, yes. We have spoken before about the Law of Thriller and the Law of Appetite for Destruction, both of which effectively killed authors intent on either maintaining that standard or bettering it. (The Law of Heartbreak Hotel had stranger but ultimately no less nefarious outworkings). There is very little peace available to those who live in the shadow of some great achievement–one that not only fulfills the Law of Success but redefines it. Yet as daunting as those other situations may be, the Law of Sgt Pepper (or Beatlemania, or Hey Jude, or Side 2 of Abbey Road) is pop music Sinai. Which makes it all the more miraculous that Paul McCartney is still standing, and still making music. Not just under duress, but with his sense of playfulness relatively intact. The only possible explanation I can come up with is that the man truly has found some Harrison-esque wisdom and humility of his own. Paul talks about “getting on with it”, but I’d wager there’s some grace involved. Somehow he’s been able to forgive himself for not being what he was–and forgive his audience for wanting him to be such. Otherwise, I don’t see how he could go into the studio.

All this is a very long-winded way of saying that I’ve come, in middle age, to look up to Paul once more. Not as a former Beatle or expert craftsman per se but as a human being who knows a thing or two about compassion, who, in a certain light, may have even become an embodiment of his most famous plea, to “let it be.”

Five Favorite Post-2000 McCartney Songs

COMMENTS

3 responses to “The Ever Present Past of the Beatles (and the Saddest Record of the Year)”

Leave a Reply

Another terrific music essay, Dave. Many will prefer that McCartney go home, have a glass of wine and stay out of the studio. Not me. I like NEW. Not all of it, but a lot. Your piece points out something I’ve observed in my advanced years…as much as you change over the years, the kid in you remains the kid in you. Isn’t that why Paul goes back to the studio? It’s probably why I’m commenting when I should just go water the plants.

Maybe Paul doesn’t try to give the public what he thinks it wants. Maybe he is what he is and it just comes out, whether former Beatle or as Sir Paul.