Ladies and gentlemen, the opening chapter of A Mess of Help: From the Crucified Soul of Rock n Roll:

I had tickets to see Nirvana in concert when Kurt Cobain killed himself. My friend and I had been looking forward to the show for months—it had already been postponed once—so the news of his death threw me even more than it might have otherwise.

I’ll never forget where I was when I heard: riding on a train in Germany, where my family was living at the time, and spying the headline in the newspaper of the passenger sitting next to me. I remember being surprised at how physical the shock felt, like a shot in the gut.

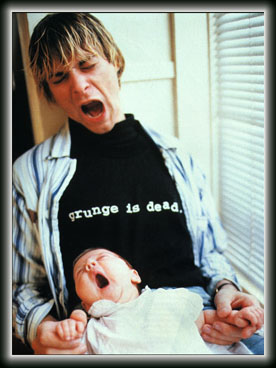

My Nirvana obsession coincided neatly with our family’s time abroad. is was not an arbitrary occurrence. Fourteen year-old boys are already pretty testy, but yank them not only out of their social circle and school but also their country (and native language!), and the storm-clouds will loom. Mix in some hormonal confusion and delay their growth spurts by a few years (relative to their class and teammates), and some adolescent rage is a foregone conclusion.

These days such a kid would probably found their way toward a certain type of hip-hop; in 1993 it was grunge, and all the flannel trappings thereof. e six-CD changer in my stereo system soundtracked those years, and on any given day Alice in Chains, Screaming Trees, Soundgarden, Pearl Jam, and Nirvana occupied at least five of the trays, with the last one being reserved for either the suddenly unfashionable GNR or, curiously enough, U2’s Achtung Baby.

Then a funny thing happened. Cobain’s suicide happened in the spring, just around the time I had finally adjusted to my new surroundings. Over the ensuing weeks, I found myself listening to less and less Nirvana, or grunge, period. When their Unplugged in New York disc finally came out (we had been playing our VHS version ragged for months at that point), I much preferred their cover of David Bowie’s “The Man Who Sold the World” to the band’s original material. at performance led me to Bowie’s Ziggy Stardust, which put me on a whole new tack.

Seattle faded into the background and stayed there, give or take a few Pearl Jam concerts during college. In fact, I hadn’t listened to Nirvana’s swansong, In Utero, for almost twenty years when I queued it up recently and let the associations wash back in. The record has aged surprisingly well. Next to Nevermind, it sounds downright fresh.

We who considered ourselves the diehard Nirvana fans adopted In Utero as an identity marker when it first came out. You could judge someone’s worth and value by whether or not they ‘got it’. The truer the fan, the more caustic their favorite track. I’m embarrassed to admit that I once claimed “Milk It” was my favorite by a mile. (Note: “Milk It” is no one’s favorite.)

The record was consciously set up to weed out the ‘wrong’ kind of fans, i.e., those who merely liked the songs but didn’t grasp the full essence of the band, aesthetic, political, or otherwise. To convince the band to go into the studio with him, producer and engineer Steve Albini composed something of a manifesto:

“I’m only interested in working on records that legitimately reflect the band’s own perception of their music and existence… Making a seamless record, where every note and syllable is in place and every bass drum is identical, is no trick. Any idiot with the patience and the budget to allow such foolishness can do it. I prefer to work on records that aspire to greater things, like originality, personality and enthusiasm…

Some people in my position would expect an increase in business a er being associated with your band. I, however, already have more work than I can handle, and frankly, the kind of people such superficialities will attract are not people I want to work with.

The purity of purpose behind the whole thing seems pretty at odds with Cobain’s sarcasm, but this was the 90s, and superficiality—a synonym for commercialism—was taken very seriously, an unforgivable sin if ever there was one.

What about the music, though—does it stand up? Well, yes. The songwriting is sharp and the performances explosive. On one of the album’s anniversaries, a prominent reviewer noted that “[In Utero is] funny, ugly, and as near to perfect as a band that isn’t interested in perfection might want to get.” It is certainly nowhere near as “difficult” as I remember it being at the time. The melodicism may be a little obscured in places, but it’s still there. Cobain’s singing never had a chance to fall into self-parody; he lays it on the line in every single vocal. And for all Steve Albini’s self-importance, the record remains his shining moment. is is producer (or “engineer”) as more than sonic architect. Albini was a svengali. Think Jim Dickinson on Big Star’s Third.

Even the lyrics still strike a chord. “Heart-Shaped Box” remains one of the most misanthropic and conflicted love songs ever put to tape, while the resigned self-pity and politically incorrect wariness of “All Apologies” still rings true and maybe even a little prophetic.

That’s all well and good, but why another essay about a band that has been written about incessantly? The answer has to do with the movie High Fidelity. That beloved film, based on the beloved book by Nick Hornby, opens with the protagonist, Rob (John Cusack), asking the audience, “Do I listen to pop music because I’m miserable? Or am I miserable because I listen to pop music?” Rob doesn’t understand why people worry so much about the effects of violent video games but not the potential damage of song after song on the radio about heartbreak and pain.

It is a profound question, and a far cry from the one I was asked most often during my years working as a youth minister. Once kids caught a glimpse of how much my inner world revolved around music, they would invariably seek my input on what they should listen to. What should be embraced and what should be avoided? What is ‘commendable’ and what’s not? In pop culture, where is the line between appropriate and inappropriate?

Such curiosity is, by and large, a good thing. Most (youth) ministers have plenty of wisdom to share on the subject, and even if they don’t, it is a good conversation starter. But that line of inquiry also belies a sad truth about the way many religious people perceive culture. Culture, especially of the popular variety, has all too often been an area of life shrouded in words like ‘should’ and ‘ought’, a place of guilt (and law) and therefore concealment—there’s what we are supposed to consume, what we may even say we consume, and then there is what we actually consume.

This is more than a ‘guilty pleasure’ phenomenon; religious or not, when we cast pop culture as forbidden fruit, we do ourselves and our children a disservice. e coming-of-age stories are well-worn: ‘I’ll never forget the day my parents found my stash of Metallica CDs’. ‘We were only ever allowed to listen to Christian music, so when my cousin’s friend played me that Eminem track in his car, I started counting the days until I could get my own place and blast hip-hop’.

The real issue, however, is not that we make a questionable movie or band that much more attractive with our restrictions; it’s that we miss out on an opportunity to ask a deeper (and ultimately more biblical) question: what is it inside of us that makes us want to consume what we actually do want to consume? After all, the Bible is fairly unclear on the subject of appropriate television. We may be able to cobble together an answer, and it may even make good sense, but it will inevitably differ from that of our neighbor.

Fortunately, Jesus more or less directly addresses the High Fidelity quandary. Mark records him saying, “Nothing outside a person can defile them by going into them. Rather, it is what comes out of a person that defiles them.” (Mark 14b-15). Sin flows inside-out rather than outside-in. To paraphrase St. Paul in Romans 5, it is inherited, not achieved.

Fortunately, Jesus more or less directly addresses the High Fidelity quandary. Mark records him saying, “Nothing outside a person can defile them by going into them. Rather, it is what comes out of a person that defiles them.” (Mark 14b-15). Sin flows inside-out rather than outside-in. To paraphrase St. Paul in Romans 5, it is inherited, not achieved.

For a piece of culture to gain traction in the viewer or consumer, in other words, it has to find an internal foothold first. Which is another way of saying that we listen to pop music because we are miserable, not the other way around. e enemy is not out there. When we blame media for our problems with anger, or lust, or anxiety, we are more than likely ignoring the logs in our own eyes.

This doesn’t mean that cultural artifacts are innocuous or have no power in and of themselves—thank God they do! But that power may look different than we often presume it does.

Which brings me back to Nirvana. In the midst of a difficult and frustrating time, I gravitated toward music that resonated with and maybe even indulged my agitation. I do not mean to imply that Cobain’s work was emotionally monochrome; there is a lot going on in it, especially on In Utero. But to my fourteen year-old ears, it was the disaffection that mattered most. It gave voice to what was going on inside of me. I was confused about my foreign surroundings and my place in them. I missed my friends and my native tongue. I was frustrated that puberty was not happening quickly enough.11 I wanted to be good at something (and I wanted one of the frauleins to notice).

When those feelings and circumstances subsided, it was no coincidence that certain records began to gather dust. In fact, the very next year I checked The Beach Boys’ Good Vibrations boxed-set out of my new stateside school’s library, and the rest is history. Not that I never felt aggression or frustration ever again, simply that my taste shifted significantly, and it was not a conscious act of will.

I give my parents a lot of credit. I can only imagine how alienated they must have felt when they would come into my room on Heinlenstrasse and hear Rage Against the Machine blaring from the speakers. They were wise enough to know that if they had forced the issue and made me throw out those abrasive CDs, the feelings would not have disappeared. They would have festered and grown, the forbiddance being yet another thing to be angry about.

I’m not positive, but I suspect that what they heard emanating from upstairs was the sound of abreaction: of music bringing feelings to the surface that were too unpleasant or scary for my adolescent self to confront directly. They must have known, instinctually if not experientially, that the misery inside must be dragged into the light and embraced if it is to be diminished—and caustic rock n’ roll is as harmless a vehicle as any parent could hope for. Frustrations like mine couldn’t be gotten around, only through; a little teenage angst now would spare their son a lot of adult rage later.

This, I’d wager, is what we mean when we talk about the therapeutic value of music. Not that it makes us feel better, but that it gives us permission to feel worse. To come as we are, in other words, doused in mud and soaked in bleach.

COMMENTS

23 responses to “Did I Listen to Nirvana Because I Was Angry? Or Was I Angry Because I Listened to Nirvana?”

Leave a Reply

When does the collected music essays of DZ come out? We’re waiting; serve the servants.

I wonder if you were in a laundry room when that conclusion came to you…

What a great piece!!! This is something that every parent / youth minister should read. Where would all those painful emotions go without the sad music? I find that music is one of the biggest gifts I have in life- it gives a voice to the sorrow / pain / anxiety. Kind of gets it all out because I feel like the music is an actual voice to the emotion, and then they are out there, and “spoken” and all that’s left is a restful feeling of being understood and calmed. The sadder the better. Take this from someone who’s been listening to melancholic music for decades 🙂 So healing!

I really love this piece.

I have never liked “christain music” and have always listen to secular. So my children listen to what I listen to. BUT I have a rule: If I can’t dance, clap, shout and worship the Lord Jesus in the same honesty that I listen to secular music then I would have to STOP.

What James said. ^^^

“I’ll never forget the day my parents found my stash of Metallica CDs.”

I’ll never forget when my parents found my collection of KISS cards. Mom burned them. Do you know what those would be worth today?!?!?

A few weeks ago I was watching Nardwar’s interview of Skrillex and my kids were shocked. “You like Skrillex??” they shrieked. “Yeah”, I said. “Seems like a super smart kid with a ton of talent. Hopefully they come to Bemidji sometime. We can all sit together.” I haven’t heard them play Skrillex since then . . . but I do.

Great piece.

As far as the chicken/egg question of listening to grunge making you angry versus being angry and listening to grunge, I think the answer is clearly, theologically, as you suggest, the latter. However, there is a reenforcing feedback loop. Our consumption shapes our desires toward a certain end – sometimes in a way that is difficult to withdraw later, even if we wish we could.

That is why, with my own son, I would not put the kibosh on (whatever the contemporary equivalent) of Rage Against the Machine, but porn would be a definite no. It’s long-term destructive power is more akin to cocaine than listening to bad pop music. It’s easy (and fun!) to write a piece reflecting on your possibly dubious music tastes as a teenager. (This is coming from someone whose mother burned his Boyz II Men album because it was too “sexy”. Seems funny now!) The same can’t be said for other things though.

I don’t think Nirvana’s work and porn are even remotely on the same continuum. They are categorically different.

Oh, I agree they are categorically different. But, growing up in evangelicism in the 80s and 90s, all sorts of things were conflated when it came to preaching and parenting advice. Smoking cigarettes, listening to heavy rock, porn, playing Dungeons and Dragons (or Doom) and wearing baggy pants were frequently lumped together and denounced and warned against collectively.

In hindsight of course, some of these things turn out to be substantially destructive and others probably not at all.

Opinion: Surfer Rosa is a better Steve Albini-produced album than In Utero. *ducks for civer*

Wonderful article, DZ! You know how to grab my attention with superbly-used John Cusack illustrations! I will get beaten for this, but I have never listened to a Nirvana album all the way through. I need to from the sounds of it. I have been digging into the catalog of Nine Inch Nails a lot lately (another angst-inducing 90s band!) and I find myself asking these same exact questions–“What is it about Trent Reznor’s disaffection makes me supremely happy in this moment”–because I enjoy the anger and brashness and disaffection of NIN’s music. Whenever I am “justifying” my listening to it, I often tell people that I have learned more about my faith from Trent Reznor than I have from most Christian music. I tell them NIN is very theological, but it is a negative theology.

Rant, I know. All this to say that I totally get what you are saying in this post and I have to ask myself those hard questions often because I do tend to dig the darker themes and elements of music…

In other words, I have to figure out what it is inside me that makes those at the church give me the nickname “The Dark Lord of the West Coast.” Haha.

Popular Christian music? Tom Waits, I’d say. Keep the Devil down in the hole.

It is extremely hard to beat Tom Waits, William. Nice call!

‘Come On Up to the House.’

Thanks for this. I listened to a lot of Metallica, Nirvana, Alice in Chains when I was a teenager. My music tastes have branched out considerably since then, but you still can’t deny the genius of these groups. The question of how Christianity can interact with music like this is tricky indeed. This is the first article I’ve read that’s really spoken to me as a Christian who spent a lot of time listening to this music. I remember the conservative protestant attitude being “you shouldn’t listen to that stuff” and the liberal protestant attitude being “why would you want to listen to that stuff?” And neither response did much for me as an angst-filled Presbyteen. I really thought after going to college and getting into Dylan, Paul Simon, Nina Simone and co. that I would never give the old angry music another listen. But it’s hard to deny the artistry of it. I was watching Metallica perform “For Whom the Bell Tolls” on Colbert the other night and I couldn’t help thinking “this may be angry music but it’s pretty brilliant.” The ironic thing is that the phrase “For Whom the Bell Tolls” originates with John Donne, one of the greatest Christian preachers in history. I imagine if you compared Donne’s sermon and Metallica’s lyrics you could get a real sense of how the West has changed in 400 years. The Christians who condemn Metallica and the Christians who ignore Metallica are both examples of a failed Christian response to modernity. Nietzsche said something about Wagner that I think could apply to Metallica and Nirvana:

“Here is a musician who is a greater master than anyone else in the discovering of tones, peculiar to suffering, oppressed, and tormented souls, who can endow even dumb misery with speech. Nobody can approach him in the colours of late autumn, in the indescribably touching joy of a last, a very last, and all too short gladness; he knows of a chord which expresses those secret and weird midnight hours of the soul, when cause and effect seem to have fallen asunder, and at every moment something may spring out of nonentity.”

A religion in which The Cross is central can hardly fail to appreciate such emotions when expressed in art. The challenge for the Christian artist or musician is to find a way to portray hope in the midst of such tragedy and suffering.

An amazing article!!! Although i discovered Nirvana’s music 19 years after Kurt died,but i just love it,and yes kids today usually live on hip hop n techno but i dont.I believe in Nirvana.People in my school have a weird way of reaacting to my music (fags) Any wayI already have Krist influence me to play bass. I am 17 n yes I love Nirvana.RIP Kurt.

Speak for yourself… milk it is my favorite nirvana song and has been for a long time.