To read part one, click here.

(End)notes From Underground

As much as Wallace’s bottoming out (and subsequent halfway house rehabilitation) contributed to the figure we now recognize as DFW, what proved decisive for the transformation of his moral imagination was his discovery of Fyodor Dostoevsky. Dostoevsky modeled earnest engagement with moral matters without succumbing to stale, propagandistic kitsch. As with any icon, Wallace grew to resemble Dostoevsky the more he fixed his gaze upon him and identified his experience with Dostoevsky’s. Both were authors of promise who experienced imprisonments, brushes with death, and nearly complete losses of hope before the gift of vocation arrived to transform their despair into prophetic vision.

Wallace’s essay “Joseph Frank’s Dostoevsky” gives us fascinating glimpses of the collision between pure reflection and anxious handwringing as Wallace is confronted by the very thing that theorists had assured him he could not encounter: the voice of the author. As he reviews Frank’s biography of Dostoevsky, explosions of associative thought interrupt his praise: how could Dostoevsky stake everything on Jesus Christ, a man within history? Was Jesus really the Son of God? And even if he was, how could what he said or did make a claim on him two thousand years later? What did, in fact, make a claim on him at all? Was the point of existence really just to stave off discomfort for as long as possible? If it was, why was there this pathological loneliness infecting the culture that played by the rules? Even as he wrangles over the legitimacy of authorial intent across three (!) footnotes you can see Dostoevsky’s voice penetrating DFW’s horizon and setting his formidable mind into motion. Try as he might, Wallace couldn’t escape Dostoevsky’s witness. Resistance was futile: the Christ-saturated Russian had midwifed the apostle of sincerity. And judgment was coming with him.

The DFW we now enshrine coalesced in this time, when his disenchantment with irony was growing in proportion to his comfortableness with sobriety. Irony, as Wallace began to see it, was a textually sophisticated form of sloth which cared not at all for meaning or dignity. Irony as worldview was a defense mechanism against vulnerability, a kind of armor that could deflect all accusations of naiveté by denying conviction. Something else was emerging as well: a nostalgia for wholeness and sincerity and community all at once. A reality he had only seen glimpsed in passing but could never pinpoint as any one particular time or setting. Dostoevsky had awakened Wallace’s hunger for Eden.

The DFW we now enshrine coalesced in this time, when his disenchantment with irony was growing in proportion to his comfortableness with sobriety. Irony, as Wallace began to see it, was a textually sophisticated form of sloth which cared not at all for meaning or dignity. Irony as worldview was a defense mechanism against vulnerability, a kind of armor that could deflect all accusations of naiveté by denying conviction. Something else was emerging as well: a nostalgia for wholeness and sincerity and community all at once. A reality he had only seen glimpsed in passing but could never pinpoint as any one particular time or setting. Dostoevsky had awakened Wallace’s hunger for Eden.

The reversal for an author who had previously plied his craft through parody and remix couldn’t be more pronounced. What the latest slew of postmodern writers had forgotten was that the first wave of against-the-grain literary rule-breaking was for a purpose. The crank-turners that followed, Wallace included, had run with the anti-form as an end in itself such that they now scorned the very idea of “purpose.” Playing solitaire in the outer limits of literary self-indulgence couldn’t be the program anymore as it couldn’t break through that solipsistic wall to reach the reader the way his burgeoning convictions demanded. Something had to be done. Pumped up on Dostoyevsky, Wallace distinguished himself from his peers with inflammatory rhetoric of redemption and hope.

This meant that simply diagnosing the world as a dark, bad place wasn’t doing enough. Lazily lobbing deconstructive grenades required zero commitment, and did nothing to repair or even celebrate the capacities for being human we somehow still possess in spite of the world’s awfulness. “Really good fiction could have as dark a worldview as it wished,” he said in an interview with the Review of Contemporary Fiction, “but it’d find a way both to depict this world and to illuminate the possibilities for being alive and human in it.” Fiction, Wallace waxed, “locate[s] and applies CPR to those elements of what’s human and magical that still live and glow despite the times’ darkness,” then added, “Fiction’s about what it is to be a fucking human being.”

Furthermore, he called for a moratorium on irony, insisting it had no power to fix what was broken. His diagnosis: it was a pressurized armor against the vacuum of meaning, another anesthetic. But irony as a worldview couldn’t hold off the implosion indefinitely nor retrieve what had been lost. Part of fiction’s job, he declared, was to “aggravate this sense of entrapment and loneliness and death in people, to move people to countenance it, since any possible human redemption requires us first to face what’s dreadful, what we want to deny.” Wallace was on a mission to disturb the comfortable and comfort the disturbed.

Furthermore, he called for a moratorium on irony, insisting it had no power to fix what was broken. His diagnosis: it was a pressurized armor against the vacuum of meaning, another anesthetic. But irony as a worldview couldn’t hold off the implosion indefinitely nor retrieve what had been lost. Part of fiction’s job, he declared, was to “aggravate this sense of entrapment and loneliness and death in people, to move people to countenance it, since any possible human redemption requires us first to face what’s dreadful, what we want to deny.” Wallace was on a mission to disturb the comfortable and comfort the disturbed.

All the same, he couldn’t wind back the clock and simply replicate Dostoevsky–his voice and sensibilities were grounded in the stylistic breakthroughs and spiritual pitfalls of the postmodern era. Infinite Jest was a first step towards developing a synthesis between classic realism of the Dostoevsky sort and the avant garde fiction whose form reflected the fragmentation of the contemporary world. IJ’s fractures were fractals inviting closer and closer inspection, revealing order on scales higher than our intellectual culture had trained us to look for. The fragments weren’t all there is, Wallace was demonstrating. The fragments are fragments of something: a shattered something, yes, but something that could conceivably be pieced together again and reunited, a something every living person ached for in their souls. There was a resolution, even if it waited just off the page.

The world’s and Infinite Jest’s plots are both oriented towards an eschatological wholeness that is more than simply the concatenation of the million mini-plots and intrigues its characters embody and act within: the resolution turns on reversals and upheavals that simply can’t be anticipated, that can only be retroactively recognized. The Eschaton the Enfield Tennis Academy students make a game of is a real future awaiting this broken world, and the dissolution of its fractures will reveal an endpoint no analogy our present word-shaped world can suffice to envision.

Redeeming the Fragments

Wallace joked at the time that he was simply becoming a “Jamesian moralist” in crafting Infinite Jest, but perhaps he was more honest than anyone realized. IJ’s endnote strategies subvert themselves as they create an implied omniscient narrator. Though their form honors postmodern aesthetics, their cumulative metacontent undermines the fragmentation postmodernism had taught was ultimate.

Indeed, the novel’s endnotes punctuate the progression of the plot to draw the reader into knowledge the plot by itself cannot disclose: they are the insights of a godlike observer, empathetically deciphering the motivations and of dozens of disparate persons, insights postmodernity had assured us were impossible. Rather than disrupting the flow of text directly as Wallace’s precursors had, his endnotes created a textual structure with two planes, an above and a below which never crystallized into a dichotomy. If one didn’t know better, the immanent/transcendent unity of insight Wallace wove into the novel’s structure almost seems to resemble the unity of insight within the God-Man, Jesus Christ. But I’m sure Dostoevsky had nothing to do with that.

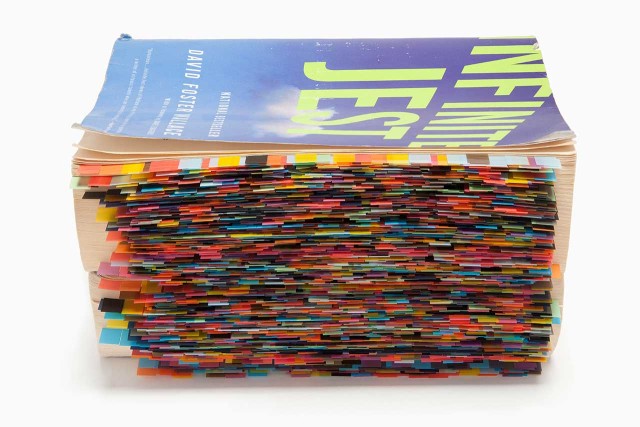

The physical act of flipping back and forth between hundreds of pages to read the endnotes forces the reader to commit to these characters, to engage them as complex personalities, to invest in understanding them on their own terms and not the reader’s. This spiraling motion collapses our solipsism and the solipsism of the characters as we follow Wallace’s lead and transgress the borders of our “skull-sized kingdoms” and theirs. Like the burnouts at Ennet House, we are planted in a context and given no other option if we’re going to make it through this but to pour ourselves into those we probably would never choose to associate ourselves with. It’s not just at Ennet House, though: IJ is populated with multitudes of difficult, distasteful people blissfully unaware of their absurdity, which means we as readers are right at home with them. And if we can also let the unpleasant realities we want so desperately to silence speak their word to us, we can ride their coat-tails to redemption.

via infinitesummer.com

Infinite Casuistry

And here is where we drill down to what is most heartrendingly exquisite about Infinite Jest: its immaculate union of uncontrived characterization with intricate plotting and incisive theological overtones. And here, again, is where Wallace learned well from his new master. For whereas a Tolstoy peopled his fiction with miniature mouthpieces of what he thought, Dostoevsky crafted characters who were not simply himself textualized onto the page. Dostoevsky’s characters defied him in their egocentric assertions of self, reason and morality be damned. Dostevsky modeled in his fiction a paradigm for God’s action in the world as author and sustainer of frequently rebellious creatures. And this served Wallace well as dug in to depict the spiritual vacuum he and we call home.

His recalibrated moral sense manifests itself in words that could have been lifted from C. S. Lewis:

This had been one of Hal’s deepest and most pregnant abstractions… That we’re all lonely for something we don’t know we’re lonely for. How else to explain the curious feeling that he goes around feeling like he misses somebody he’s never even met? Without that universalizing abstraction, the feeling would make no sense. (IJ, 1053, note 281.)

Compare this with Lewis’ words in his sermon, “The Weight of Glory”:

In speaking of this desire for our own far-off country, which we find in ourselves even now, I feel a certain shyness. I am almost committing an indecency. I am trying to rip open the inconsolable secret in each one of you- the secret which hurts so much that you take your revenge on it by calling it names like Nostalgia and Romanticism and Adolescence; the secret also which pierces with such sweetness that when, in very intimate conversation, the mention of it becomes imminent, we grow awkward and affect to laugh at ourselves; the secret we cannot hide and cannot tell, though we desire to do both. We cannot tell it because it is a desire for something that has never actually happened in our experience. We cannot hide it because our experience is constantly suggesting it, and we betray ourselves like lovers at the mention of a name…. These things–the beauty, the memory of our own past–are good images of what we really desire; but if they are mistaken for the thing itself they turn into dumb idols, breaking the hearts of their worshipers. For they are not the thing itself; they are only the scent of a flower we have not found, the echo of a tune we have not heard, news from a country we have never yet visited.

Every player in Infinite Jest is driven by this enchantment, this instinctive urge to find home, to love and feel love reciprocated. Some act to further an ideology, others to silence the agony of addiction, but every one of them is pulled along the magnetic fields of this need to return to a wholeness none of them have ever owned. This is the longing Lewis identified as our corporate nostalgia for Eden, that inconsolable longing for the home we’ve never had, that the homes we were raised in were smaller imprints of. The houses and families we remember could never be the source of that titanic sadness, only pointers towards something magnificent we forfeited in a past that is now quarantined from our retrieval.

Every player in Infinite Jest is driven by this enchantment, this instinctive urge to find home, to love and feel love reciprocated. Some act to further an ideology, others to silence the agony of addiction, but every one of them is pulled along the magnetic fields of this need to return to a wholeness none of them have ever owned. This is the longing Lewis identified as our corporate nostalgia for Eden, that inconsolable longing for the home we’ve never had, that the homes we were raised in were smaller imprints of. The houses and families we remember could never be the source of that titanic sadness, only pointers towards something magnificent we forfeited in a past that is now quarantined from our retrieval.

Lewis, reflecting on his experiences of joy called it sehnsucht (for lack of a better denotation, inconsolable longing) but I think the better rendering of the feeling is saudade, the depths-beyond-depths melancholy for an absent loved one. For “home” is more than a place: at the deepest level of reality, home is a person. And we all come undone in His absence.

The stifling of the soul’s nostalgia for its Author keeps us curved in on ourselves and “incontinent of sentiment and need,” craving an object to spend our love upon. Consumerism appealed to that sinful incurvature by providing us with unbounded purchasing options to shore up against our ruin. But as our experience shows, consumption only amplifies the feeling of being castaways, pointlessly acquiring and upgrading only to consign it all to the junk heap. Here IJ’s enormous dump, AKA the Great Concavity/Convexity (depending on which side of the United States/Canadian border you reside), is a poignant analogue to Pascal’s famous description of the abyss in fallen man:

What is it, then, that this desire and this inability proclaim to us, but that there was once in man a true happiness of which there now remain to him only the mark and empty trace, which he in vain tries to fill from all his surroundings, seeking from things absent the help he does not obtain in things present? But these are all inadequate, because the infinite abyss can only be filled by an infinite and immutable object, that is to say, only by God Himself.

He is our only true good, and since we have forsaken him, it is a strange thing that there is nothing in nature which has not been serviceable in taking His place; the stars, the heavens, earth, the elements, plants, cabbages, leeks, animals, insects, calves, serpents, fever, pestilence, war, famine, vices, adultery, incest. And since man lost the true good, everything can appear equally good to him, even his own destruction, though so opposed to God, to reason, and to the whole course of nature. (Pensees, no. 425)

The grave of our dumb idols can never dissuade us from buying, and the grave can never be filled; its capacity only enlarges to consume our consumption and maintain the loop.

But the ultimate reason IJ remains so compelling isn’t its social critique or its hysterical wordplay (as much as they both contribute to the charm of what could otherwise be a solar system-sized bummer of a book); it’s Wallace’s characters and the destinies they join themselves to through their loves that grip us. Its characters either collapse under or arrive at themselves through the pressure of what they love; either false loves, as Augustine would diagnose them, or through genuine, self-sacrificial love for the other, as in Don Gately’s case. Don Gately, in particular, is never more himself than in his vicarious suffering for his little flock at Ennet House. Kate Gompert’s abyssal self-obsession finds a fitting end in her subjection to the Entertainment. This Augustinian notion of human flourishing and ruin fuels Wallace’s use of figures and tropes familiar to the Western literary tradition; for once, an avant garde author honors the tradition and channels its energies to freshly incarnate old symbols.

Yet to identify the straight lines of Enfield’s tennis courts or the existential abyss of the titular videotape or the Christ-likeness of Don Gately as symbols and signs isn’t to reduce IJ to allegory: it’s to recognize the lifelines that run between the everyday level of our words and actions and the imagination of an author who is both beyond and within that reality. IJ thrives on this vast network of interdependence and nested meaning.

Yet to identify the straight lines of Enfield’s tennis courts or the existential abyss of the titular videotape or the Christ-likeness of Don Gately as symbols and signs isn’t to reduce IJ to allegory: it’s to recognize the lifelines that run between the everyday level of our words and actions and the imagination of an author who is both beyond and within that reality. IJ thrives on this vast network of interdependence and nested meaning.

In service to that reality, Wallace puts his words to use as weapons against the spiritually deadening distraction and consumption that are ubiquitous in our context. But they puncture to liberate and to heal; his prose floods over the artificial barriers we’ve constructed to sound out the hollow points, revealing the structural weaknesses where force can be applied to punch through our imprisonment and escape. And as we read we find his voice insinuating itself within the sound of our own inner voice, a voice from beyond and yet within, telling us what we knew all the time to be true but were too afraid to admit was true.

You might say that Wallace fractured the fractures in order to expose the ligaments of meaning we cannot escape in our words: the covenantal threads that bind the word to the world. No matter how hard we try to erase them, they remain, for ours is a world already pregnant with meaning. That world found an advocate in David Foster Wallace. And if one thing is clear about Infinite Jest, it is this: there is an author in this text; his voice survives. IJ is a testimony that the word of the author can be preserved and heard whenever a text is opened and digested. And behind that, that the Author of all still speaks, can still be heard, still underwrites our words with His living Word.

St. Dave never quite dismantled the encagement of postmodernity to lead us out on a new exodus. But David Foster Wallace came closest to that lofty goal with Infinite Jest. After all, the prophet can only call the masses to repentance–he can never effect it himself, even if he faithfully delivers the message. The true prophet’s heart breaks when he sees the word ignored to his listeners’ peril. The best prophets are poets, piercing the darkness of contemporary society and denouncing its corruptions while simultaneously sewing light into the recesses of the soul we try to keep hidden even from ourselves.

Wallace’s world-weariness wasn’t encumbered by the dispassionate cynicism of many of his peers. His work has gained traction because of the vivacity with which he rendered both the viciousness and the sheer ecstasy of being alive in this age. For his words contain glimpses of a different way of being human, a way that hearkens back to a wholeness we can only momentarily remember, to a communion we hunger for but cannot satisfy here and now. Wallace’s work reflects his time and place but continues to speak afresh as it resounds with echoes of the Word that spoke all things into being, the Word who entered into our ruin to redeem the fragments and make all things new.

COMMENTS

One response to “The Word Within the Fracture: 20 Years of Infinite Jest, pt 2”

Leave a Reply

All I can say is Thank You. This is nigh on definitive.