In honor of the release of Harry Potter and the Cursed Child, here is another essay from our new anthology of movie essays, Mockingbird at the Movies, available in print here and on Kindle here.

Before anyone calls bluff on a Harry Potter essay found in a book about movies, let us first consider a fact about the Harry Potter movie franchise. As of July 2015, total movie sales for the eight Harry Potter films had almost surpassed total Harry Potter book sales, a ridiculous feat when you consider how much money that is (over $7 billion). And when you consider that its box office gross beats out the total tenure of the 50-year, 25-film James Bond empire, it certainly lends some cred to “the boy who lived.”

Of course, numbers hardly ever justify the cinematic quality of a film, but they do say something about us: Blockbuster films give us characters and plots with which we resonate or with which we would like to resonate (looking at you, 007). It goes without saying that readers very much resonated with Harry Potter, so much so that they took their obsessions into the theaters with them.

Why, though? What is it about Harry? Is it his lowly upbringing in the cupboard under the stairs, and his unknown superstar status? Is it the magical world of Quidditch and Thestrals and Wandmakers that we get to discover alongside him? Lord knows we’d all want a wand to choose us!

Above all, what is baffling to me is the fact that, in many churchgoing circles, the books were not read and the movies were not watched. For fear of flying brooms and werewolves, many parents forbade their children the opportunity to go to Hogwarts with Harry. Such scorn is to be expected, I suppose, especially when the themes found within the books (and not the magical feats) are the real threat. Themes like love resurrecting the dead, strength proving itself in weakness, hope shining through immense suffering—these messages will get you killed, after all.

It certainly didn’t keep the kids from reading the books or watching the movies, though. It instead offered them the mischievous lot of reading the books by flashlight under the covers and watching the DVDs at sleepovers. From these hidden places, with flying cars and live chocolate frogs, they found the wisdom hidden since the foundation of the earth. For muggles and wizards alike.

If sacraments are ‘outward signs’ of God’s hidden wisdom, these are the seven sacraments of Harry Potter.

I: The Scar

It has become the brand: the focal, jagged-tail P that’s emblazoned on X-Box games and bathmats and amusement park merchandise. Harry’s lightning-bolt scar is his Superman ‘S’. It is an ironic mark for a hero, though, because it also represents, for Harry and the rest of wizarding world, an event of immense devastation. But it is just the first hallmark of a recurring theme within the Potter chronicles: of living with one’s wounds, that only through the experience and confrontation of suffering can one ever truly live.

The origin is well known by now. When Harry was only a year old, his parents were killed by the evil Lord Voldemort. But when Voldemort tried to kill Harry, the killing curse backfired unexpectedly; Voldemort was undone. It turned out Harry had been protected by a charm Voldemort could not understand—love. All that remained of the failed curse was a lightning bolt scar on his forehead. As Dumbledore explains, “He’ll have that scar forever…Scars can come in handy. I have one myself above my left knee that is a perfect map of the London Underground.”

Dumbledore foreshadows a thread that will weave from the opening of the first film through to the final scene of the last film: A scar does mark suffering, but it may also act as an avenue through which something useful happens.

Harry grows to find that his scar is much more than a bragging right; it is a physical and mental connection to Voldemort. Harry is, despite himself, in a living communion of pain with his darkest foe, inseparably linked to him. He can sometimes see what Voldemort sees, feel what Voldemort feels. As Harry grows older, and Voldemort’s powers grow stronger, this link intensifies. Rowling portrays this wound as Harry’s cross to bear, a life inside of him that is not his own, the force of which is nearly impossible to oppose. Harry finds the link to be useful, but this proximity is also intolerable. The pain of this connection is tempered only by the very thing that also saved Harry as a child: love.

At the end of the first movie, Dumbledore explains to Harry the power that has been stamped beneath his skin—the love of his mother. Regardless of Harry’s own strength, the strength of the love he inherited is what stands in for him. To Dumbledore, Harry’s scar is also subject to the power of imputed love: “[Your mother] sacrificed herself for you, and that kind of act leaves a mark…This kind of mark cannot be seen. It lives in your very skin…Love, Harry. Love.”

Throughout the entirety of the Potter series, we find that love is Harry’s only antidote to the immense suffering brought on by his union to the darkness. Part One of the Deathly Hallows film ends with the burial of the house elf Dobby, who died to save Harry. It also ends with Voldemort’s acquisition of the Elder Wand, or the Deathstick. That these moments come together, like the night that produced Harry’s scar, demonstrates the ineffable power of death meeting the unlikely power of love. Harry finds that his mark of imputed love stands victorious, even here. Rowling writes:

[Voldemort’s] rage was dreadful and yet Harry’s grief for Dobby seemed to diminish it, so that it became a distant storm that reached Harry from across a vast, silent ocean…His scar burned, but he was master of the pain; he felt it, yet was apart of it…Grief, it seemed, drove Voldemort out…though Dumbledore, of course, would have said it was love…

II: The Mirror of Erised

Harry, in his nighttime wanderings of Hogwarts School, stumbles upon a room completely empty and unused save for an enormous mirror, the reflection of which startles him. In it, Harry glimpses his parents whom he’d never known and always longed to know.

It is no coincidence that ‘Erised’ backwards spells ‘Desire,’ the basis of the magical mirror’s enchantment. Entranced, he takes Ron the next night to show him his parents. Ron does not see Harry’s parents, though. He sees himself, older, good-looking, successful: “Do you think this mirror shows the future?” he asks. Harry responds, “How can it? All my family are dead.”

Despite Ron’s concern for Harry’s fixation with the mirror, Harry goes back a third time on the third night, only to find that this time he’s not in the room alone. Dumbledore is there, and, understanding the boy’s fascination, explains its function:

It shows us nothing more or less than the deepest, most desperate desires of our hearts…However this mirror will give us neither knowledge nor truth. Men have wasted away before it, entranced by what they have seen, or been driven mad, not knowing if what it shows is real or even possible.

The mirror, in fact, does what all mirrors do, albeit on the deepest level: The Mirror of Erised reflects the heart’s desire. In the same way that an average mirror reflects to the viewer a self constrained by its external appearances, this magical mirror makes manifest those invisible deities which lie below the surface. It reveals those idols upon which we’d hang our hat every time, giving us the glory story we wish we had.

Rowling betrays a low anthropology here, observing that human beings are incurable escapists. No one wants to accept things as they are, and the deepest-set ‘if only…’ can easily arrest anyone’s ability to live the lives they’ve actually been given. Harry and Ron are drawn into their custom-made fantasy worlds. The Mirror does not reveal a desire to live for others, a desire to love compassionately, to seek truth. Instead, it shows us that the desires of the heart are always self-oriented. Rather than some external Odyssean temptation to the courageous and pure-hearted, this mirror conveys, as Dumbledore explains to Harry, what lies precisely within us.

Dumbledore tells Harry that only a truly happy man could look into the Mirror of Erised and see himself as he is. The Mirror of Erised is powerless over a person who has confronted the givens and accepted them. In Rowling’s universe, then, true contentment—if it is possible—cannot bypass self-knowledge. True happiness means leaving our “private hall of flattering mirrors” (Franzen) and seeing first the person we’re not so proud to see. At this juncture, we are left to wonder, is happiness even possible if it requires the stamina to see the worst in ourselves?

It seems that if it was ever possible, Dumbledore would be the virtuous example. Yet, in the Deathly Hallows, Harry discovers that Dumbledore, too, could not escape his own desire for power. He understood Harry’s addiction because he, too, had similar susceptibilities. More on this later.

It is for this reason, the Mirror’s lustrous allure to the addict human heart, that Dumbledore must remove the mirror from young Harry, knowing that a slap on the wrist or word of caution would only bring him back for more. He doesn’t want Harry maddened by a reality that is unreality, paralyzed by his own picture of life. Dumbledore says it best in his hospital visitation at the end of The Sorcerer’s Stone. Harry is befuddled that Dumbledore would have destroyed the Sorcerer’s Stone, with its abilities to give eternal life and endless riches, to which Dumbledore replies, with delightful wit:

You know, the Stone was really not such a wonderful thing. As much money and life as you could want! The two things most human beings would choose above all—the trouble is, humans do have a knack of choosing precisely those things that are worst for them.

III: The Dementor

Harry first meets a dementor on a train to Hogwarts School in The Prisoner of Azkaban, in his third year at Hogwarts. The famed mass murderer Sirius Black (whose innocence is undisclosed until the end of the film) has escaped Azkaban Prison—something unheard of in the magical world—with the apparent intent of finding Harry and killing him. As Harry’s new professor, Lupin, informs him, dementors are the soulless guards of the Prison, “set on a tiny island, way out to sea, but they don’t need walls or water to keep the prisoners in, not when they’re all trapped inside their own heads, incapable of a single cheerful thought.” During Harry’s first experience with the dementor on the train, a rush of cold enters his body, and before he loses consciousness, he hears the scream of his murdered mother. Harry is ashamed he can’t seem to ‘handle’ their presence as well as his peers, until Lupin explains that “Dementors are among the foulest creatures to walk this earth. They feed on every good feeling, every happy memory until a person is left with nothing but his worst experiences.”

It is not Harry’s lack of courage or fortitude that weakens him before the dementor but the anguish of his past. Feeding on happy moments, the dementor leaves its victims in a pit of depression, with only their worst memories, robbed also of the ability to pull themselves out of hopelessness. Ron notes that he “felt like [he] would never be cheerful again.” Such defenselessness and hopelessness points to the world of depression. Rowling herself mentioned that the dementor concept came from a time when she was throttled by severe depression, where she felt “that very deadened feeling, which is so very different from feeling sad.”[1]

The Dementor’s Kiss, its final blow, is one in which the victim’s soul is literally sucked out. This, according to Professor Lupin, is worse than death.

The only charm which can defend someone from the dementor is the Patronus Charm. Rather than battling the dementor on one’s own, the wizard who conjures the Patronus Charm is summoning a power greater than they are, which will stand before the dementor and defend them. It is a complicated spell—one must connect with and focus upon a memory that is powerful enough to protect. If one’s picture of happiness is not rooted in love but in exhilaration or excitement, the Patronus founders. In other words, the strength of the Patronus is as strong as the love that generates it.

The Patronus is a positive force that stands between the dementor and the wizard. In Latin, the charm’s incantation (Expecto Patronum) means ‘I await a protector.’ The Patronus charm works as a stand-in for the wizard, a spiritual force that acts as substitute prey for the dementors to feed on. The reason that Harry attracts the attention of dementors is also the same reason that he is one of the youngest wizards to have ever conjured a Patronus: He is stamped (imputed) by the powerful love of his parents. The murder of his parents is more than an eternal stain upon his memory—it signifies the power of sacrifice that gave him life. Through it, Harry has a protector, who communes with him in the deepest depths of grief.

IV: The Pensieve

Dumbledore’s Pensieve is a shallow stone basin of milky, ethereal liquid—like a birdbath—wherein one drops the hair-thin substance of one’s memory. Once dropped into the Pensieve, the wizard is transported to the scene of the memory from the perspective of the memory’s beholder. The ‘visiting’ wizard cannot participate in the memory, but can behold it to better understand why things are the way they are:

I sometimes find, and I am sure you know the feeling, that I simply have too many thoughts and memories crammed into my mind…At these times I use the Pensieve. One simply siphons the excess thoughts from one’s mind, pours them into the basin, and examines them at one’s leisure. It becomes easier to spot patterns and links, you understand, when they are in this form.

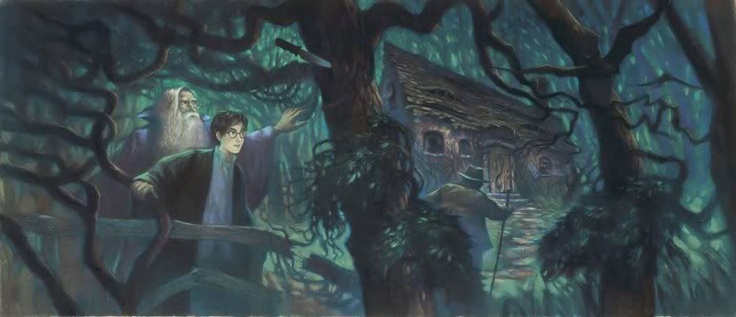

The Pensieve, in short, helps make sense of things. It acts as a record book of the shaping elements of one’s personal history, a proper understanding of what one has dealt with and what one carries. In the sixth installment of the saga, Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince, Harry and Dumbledore use it precisely to examine the memories and experiences that transformed the infamous Hogwarts student, Tom Riddle, into Lord Voldemort. Harry doesn’t understand why such archaeology is necessary, but Dumbledore seems to treasure the memories as vital clues in knowing their enemy. Here Dumbledore invites Harry into his first memory of Tom, a troubled and friendless orphan with a penchant for pain.

After this particular trip into the Pensieve, Dumbledore notes key features of Tom’s psychology: Tom seeks self-sufficiency and isolation at every turn. He has no friends, and has never wanted them. And, above all else, he seeks power.

The Pensieve shows Harry and Dumbledore that humans are inheritors and effectors of a condition. The Pensieve, in allowing one to peer into what makes people who they are, shows that humans do not exist and act ex nihilo (out of nothing), but through the “marshes of memory and experience.”

Moreover, though, the Pensieve is an instrument which allows a wizard to confront his or her offenders/enemies by understanding their heritage. A conjunction of ‘sieve’ (sift, sort) and ‘pensive’ (thoughtful, reflective), the Pensieve is a weapon that first listens to and receives counsel from the past, that seeks to reconcile the present by coming to grips with, as the church confession describes, “things done and left undone.”

V: The Mudblood

“No one asked your opinion, you filthy little Mudblood,” Malfoy spits in the second movie. It’s not just any wizard bad word, and it’s not a catchall insult any one person can use to offend another—even worse, it is about something true. In this case, the first time Harry Potter hears the word ‘mudblood,’ Draco Malfoy is hurling it at Hermione Granger. It instantaneously incites violence. Ron, defending Hermione, casts a curse on Draco that backfires on himself, leaving him barfing up slugs—a kid-friendly diffusion of the gravity of the moment—but Harry, being new to the wizarding world, needs an explanation. “Dirty blood, see. Common blood. It’s ridiculous,” Ron says. “Most wizards these days are half-blood anyway. If we hadn’t married Muggles we’d’ve died out.”

Rowling is, of course, drawing some anthropological continuity between our two worlds. The incredibility of Harry’s world can be off-putting, and yet throughout the series, we find the inner lives of wizards to be no different than our very own. Wizards are humans, just as love-hungry and power-hungry, compassion-seeking and conniving. ‘Mudblood’ is poignant because, although the reader is finding out its meaning alongside Harry and Hermione, it turns the reader back on his or her own world of bigots and pharisees, outcasts and ingrates. It takes the potentially unbelievable world of Wingardium Leviosa and Crumple-Horned Snorkacks and grounds it in the weight of the human rift. Exclusion is not new to Harry, of course—he spent his first twelve years in the closet under the stairs—but he had also heard such distinctions from Draco before his first year at Hogwarts:

I really don’t think they should let the other sort in, do you? They’re just not the same, they’ve never been brought up to know our ways. Some of them have never even heard of Hogwarts until they get the letter, imagine. I think they should keep it in the old wizarding families.

Little did Draco know that Harry is one of those kids, who didn’t know about Hogwarts until he was taken. Ironically, Harry is the meshing of the two worlds. He is in the “old wizarding families”—far more famous than the Malfoys and the Longbottoms—but any credit bestowed by being a ‘pureblood’ is lost on him. He knows nothing about it.

‘Mudblood,’ like the law, marks distinction. It is ironic because Hermione, who is far more distinguished than her peers in actual wizarding talent, finds herself excluded by a worthiness she can’t prove or earn. A daughter of two Muggles, she is—to the Slytherins, the Malfoys, the purebloods—an outsider. Despite Harry’s and Ron’s words of comfort, the place that had once been a celebration of her peculiar gifts now represents, just like any other place, the confusing rift between the haves and have-nots.

If the question is, “Magic, who really has it, who doesn’t?” then ‘Mudblood’ exposes the schism that will later be exemplified in the final battle. On one side, there are those pure-bloods who make the distinctions, and use them to seek control. Led by Lord Voldemort (who is not pureblood, as it happens), they intend to ‘cleanse’ the magical world with a rigorous reinterpretation of who is worthy. They do so by upending the Ministry of Magic, by interrogating those with questionable blood heritage, and by refusing Muggle-borns admission to Hogwarts. It goes without saying, though, that there are no friends on this side; there is instead perpetual suspicion and surveillance. Once one claims to be ‘pureblood,’ he or she has only begun the ordeal of having to prove oneself, or pretending to act like one, as Hermione suspects: “The Death Eaters can’t all be pureblood, there aren’t enough pureblood wizards left. I expect most of them are half-bloods, pretending to be pure.”

On the other side of the final battle are the Mudbloods, the Half-Bloods, and the ‘Blood-Traitors,’ purebloods like the Weasleys, who see no distinction, who believe in the magic over the heritage. In this sense, it is some Spirit of Magic that operates universally (“The wand chooses the wizard!” says Ollivander) and not the blood. This side, where Dumbledore stands at the helm, believes in magic as a great leveler, where all are equally chosen. Wizards and witches are magical because magic has been given—magic chose them! Hermione, in this sense, is righteous. On this side, then, the magic—which sounds a lot like the Holy Spirit—will do the fighting for them. There is nothing to fear. It for this reason that Hermione, in The Deathly Hallows, is able to say:

“I’m hunted quite as much as any goblin or elf, Griphook! I’m a Mudblood!”

Ron started, “Don’t call yourself—”

“Why shouldn’t I? Mudblood, and proud of it!”

VI: The Horcrux

SLUGHORN: You must understand that the soul is supposed to remain intact and whole. Splitting it is an act of violation, it is against nature.

RIDDLE: But how do you do it?

SLUGHORN: By an act of evil—the supreme act of evil. By committing murder. Killing rips the soul apart. The wizard intent upon creating a Horcrux would use the damage to his advantage: He would encase the torn portion—There is a spell, do not ask me, I don’t know!…Do I look as though I have tried it—do I look like a killer?

A Horcrux is an item within which a wizard has stored a portion of his soul, thus allowing a portion of himself to live on if his body is destroyed. As a student, Tom Riddle (Voldemort) learned about Horcruxes through his (and later Harry’s) Dark Arts professor, Horace Slughorn. The process of creating a Horcrux is extremely gruesome, as it requires the murder of another, and repudiates one’s selfhood by fracturing it. Very few dark wizards have attempted the process even once. In the pursuit and study of Voldemort, Dumbledore slowly discovers that the situation “is beyond anything I imagined”:

The careless way in which Voldemort regarded this (first) Horcrux seemed most ominous to me. It suggested that he must have made—or been planning to make—more Horcruxes, so that the loss of his first would not be so detrimental. I did not wish to believe it, but nothing else seemed to make sense.

Voldemort has, in fact, created seven Horcruxes, strewing himself into seven hidden compartments, including his own living body, thus living as long as these portions of his soul remain intact. This division, however unstable it renders the soul (the wizard becomes, as Dumbledore tells Harry, “most unhuman”), provides eternity for the wizard willing to kill. This eternity is cursory, though, in that one’s soul dwells in a substitute that is not its true home. Thus, the Horcrux is a noteworthy if perverse example of Paul’s inversion of “strength as weakness.” A Horcrux may promise eternity, but it is an eternally unstable, soulless strength, deposited in fragile foundations. This is why, when Harry asks whether or not Voldemort feels a part of himself destroyed when a Horcrux is destroyed, Dumbledore responds, “I believe that Voldemort is so immersed in evil, and these crucial parts of himself have been detached for so long, he does not feel as we do. Perhaps, at the point of death, he might be aware of loss…”

In a theological sense, a Horcrux is an inverted representation of substitutionary atonement. Voldemort’s suffering as a human—his loveless childhood, his estrangement in an orphanage, his defensive arrogance and solitude—created a fierce desire for substitution, for someone (something) to stand in for his pain. Much like Dorian Gray’s portrait, his sins and sufferings are transferred onto (and within) a façade. While he is given life superficially, the cost of this substitution is profound. According to Hermione’s reading, the splitting of one’s soul in such a way leaves one with only the hope of healing through repentance:

RON: Isn’t there any way of putting yourself back together?

HERMIONE: Yes, but it would be excruciatingly painful…Remorse. You’ve got to really feel what you’ve done. There’s a footnote. Apparently the pain of it can destroy you. I can’t see Voldemort attempting it somehow, can you?

Like most villains, Voldemort has chosen the path that will ultimately lead to his demise. And, like most villains, that demise is rooted in his will to power. Voldemort’s pursuit of immortality has also made him strangely unwieldy. He is, in his immense strength, vulnerable and out of control. In his greed for standalone power, the wreckage required to get him there has involuntarily broken his strength.

There is also a power Voldemort cannot understand. The love of Harry’s mother, a love that unequivocally surrenders one’s life for the life of another (proper substitutionary atonement!) is a power too furtive to be noticed by the Dark Lord. Like Calvary, it is a power that makes itself known through death, something Voldemort would never have the notion to see. This love is also what unwittingly ties him to his fate. His will to power is cursed by love. Dumbledore explains it to Harry:

You were the seventh Horcrux, Harry, the Horcrux he never meant to make…He left part of himself latched to you, the would-be victim who had survived…He took your blood believing it would strengthen him. He took into his body a tiny part of the enchantment your mother laid upon you when she died for you. His body keeps her sacrifice alive, and while that enchantment survives, so do you and so does Voldemort’s one last hope for himself.

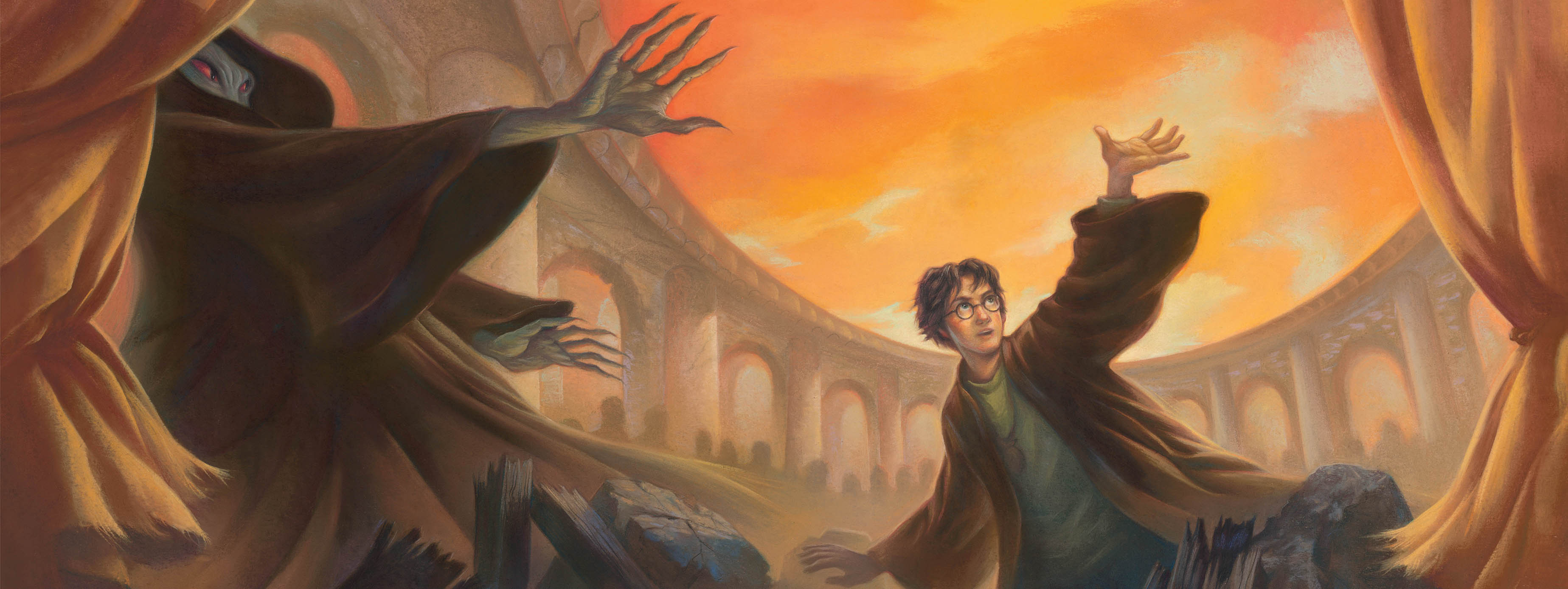

VII: The Deathly Hallows

Three objects, or Hallows, which, if united, will make the possessor master of Death … Master … Conquerer … Vanquisher … The last enemy that shall be destroyed is death …

The myth of the Deathly Hallows is only sparsely known throughout the wizarding world, though the very old story from which it is derived is as well-known as a child’s nursery rhyme. “The Tale of the Three Brothers” introduces the Hallows, though not explicitly, as Xenophilus Lovegood explains to Harry, Ron, and Hermione:

That (tale) is a children’s tale, told to amuse rather than to instruct. Those of us who understand these matters, however, recognize that the ancient story refers to three objects, or Hallows, which, if united, will make the possessor the master of Death.

It is not a subtle hint that a children’s story would contain the key to the magical universe, and that such wisdom would be foolishness to Voldemort. Nonetheless, the Deathly Hallows are: the Cloak of Invisibility, the Resurrection Stone, and the Elder Wand. Historically speaking, they are the original relics of the three Peverell Brothers, incredibly talented wizards who each crafted an instrument of magic that could make them death-proof.

Each brother used his particular Hallow to respond to the reality of death. The fashioner of the Elder Wand sought the power to kill his enemies; the brother with the Resurrection Stone sought the power to bring life back to those who are dead; and the brother with the Cloak of Invisibility wished merely to avoid death until the time was right. As the tale illustrates, the first two brothers—who essentially wished to appropriate the powers of Death—found their new gifts unfitting, the use of them resulting in a strange lifelessness. In identifying themselves with powers that were not theirs, they die. The third brother, on the other hand, wanted no power but to be left to grow old on his own—his Hallow (the Invisibility Cloak, now owned by Harry) represents an acceptance of mortality. Because he surrenders to impending death, he lives long and “greets death as an old friend.”

The possession of the Hallows, then, provides a second, equally dangerous route to everlasting life alongside the Horcrux. While the creation of the Horcrux gives the creator eternity at the expense of his soul, the Hallows provide their master with powers too tempting to refuse, and consequences too heavy to carry. Both the Hallows and the Horcruxes whet the appetite for the strongest human delusion: power. For this reason Harry’s ethereal reunion with Dumbledore presents him with an old man’s confession, “Real, and dangerous, and a lure for fools…And I was such a fool…Master of Death, Harry, Master of Death! Was I better, ultimately, than Voldemort? No…I too sought a way to conquer death, Harry.”

Dumbledore had been so allured by the power of the Deathly Hallows that he had tried on the ring of the Resurrection Stone, despite his knowledge that Voldemort had made it a Horcrux. Dumbledore’s motive was to atone for the guilt of the mysterious death of his sister, Ariana. While it was a kind of self-atonement, a different kind of power hunger, it was still his folly: His use of the Stone meant his death.

It becomes obvious to Harry that Voldemort does not know about the Deathly Hallows, mainly because Voldemort had turned the ring upon which the Resurrection Stone was placed into a Horcrux. Voldemort’s chief interest is in the only Hallow that would matter to him, the Elder Wand, or the Deathstick. It is more publicly known because “the bloody trail of the Elder Wand is splattered across the pages of Wizarding history.” As Dumbledore says to Harry later:

[Voldemort] would not think that he needed the Cloak, and as for the stone, whom would he want to bring back from the dead? He fears the dead. He does not love…Voldemort, instead of asking himself what quality it was in you that had made your wand so strong, what gift you possessed that he did not, naturally set out to find the one wand that, they said, would beat any other. For him, the Elder Wand has become an obsession to rival his obsession with you. He believes that the Elder Wand removes his last weakness and makes him truly invincible.

Just as with the other two Peverell brothers, it is this flaw in Voldemort’s logic that will undo him. His quest for power has left him looking for a tool which will make him eternal, rather than seeing in Harry the eternal quality that makes him supreme. That quality, more penetrating than the power of a wand or a life-giving stone, is love. Harry, marked by the love of life lain down, carries it and is compelled to do the same. Harry, in the name of love, lays down his life so that his friends might live. And, because Harry has given up his life, he is given a proper resurrection.

This self-sacrificing love is what leads Harry into his encounter with Dumbledore, in an empty King’s Cross Station. There he recognizes that he is the unlikely Master of Death, the bespectacled descendant of the third Peverell brother and, more importantly, because he has died to death: “You are the true master of death, because the true master does not seek to run away from Death. He accepts that he must die, and understands that there are far, far worse things in the living world than dying.” It is in this faith, which looks to all the world like death, that the real magic happens. And it is the hope upon which all of us—Muggle or magic—rely.

Order your copy of Mockingbird at the Movies today!

[1]. “J. K. Rowling, the Interview,” The Times (UK), June 30, 2000.

COMMENTS

Leave a Reply