This delightful post comes from Ben Fort:

Back in September, a sermon went viral. A British pastor was praised for a grace-filled rebuttal to the burdensome false teachings found in the video of a fellow clergyman. This kind of interaction isn’t surprising to anyone on Christian Twitter, except the debate wasn’t about the Trinity or the role of women in the church. The issue was fat shaming, and the denomination was CBS. The pastor’s name is James Cordon, host of The Late Late Show. His adversary, Bill Maher, has a pulpit on his HBO show, Politically Incorrect.

The goal of humor has always been simple: get a laugh. Accomplish that goal, and you’re a good comedian. Awkward silence, not so much. But Bill Maher wasn’t criticized for being a bad comedian. He was a bad priest, using his pulpit to add burden instead of lifting it. And James Cordon wasn’t praised for being funny, but for bringing relief.

David Zahl put it well in the footnotes of Seculosity, his book about the rampant religiosity we’re seeing outside of organized religion: “In the church of seculosity, stand-up comedians (and late-night talk-show hosts) are the preachers.”

That certainly feels true with the rise of the com-ily, when a comedian pauses the jokes to sincerely address a serious issue. In the wake of national tragedies, we’re increasingly retweeting words of comfort from late-night hosts like Cordon, Trevor Noah, and Jimmy Kimmel. The peak of the comily may have come right after the 2016 presidential election, when Saturday Night Live opened with a sober lament. Kate McKinnon, dressed as Hillary Clinton, played a piano and unironically sang Leonard Cohen’s Hallelujah without any jokes.

As someone who performs and teaches at a local comedy theater, this priestly trend raises interesting questions. What is the relief of laughter, and is that enough for a hurting world? Have we been asking too little of comedians, or are we now asking too much?

During the first week of the Covid-19 outbreak, I could feel an anxiety attack brewing. These attacks are always an earthquake, and I could feel the early tremors. I felt powerless beneath the weight of the world, the rising numbers, the death toll in Italy, the loss of jobs; and also the weight of being a stay-at-home dad with a 3 year-old and a 1 year-old, which I’ve done for years but never with this little help or places to go.

My anxiety attacks always end in a sob. It’s the physical release my body needs, and I was bracing myself for the inevitability of a weepy breakdown. The tears came on a Thursday evening, but not from being overwhelmed at a news update or small humans yelling at me. I was watching Stephen Colbert deliver his show’s monologue from his front porch.

He ended his segment with a comily, which I’m sure was thoughtful and comforting, but my relief had already come. It was his jokes that made me cry, a joyful uncontrollable giggle fit. At that moment, I didn’t need his assurance that everything would be okay. I needed a reminder that I live in a world with the movie CATS, a world where professional animators work hard to edit digital cat butts. I was lamenting the loss of a sensible world, with rules that can be followed and rewarded, and Colbert reminded me that this “rational” world gave me CATS.

Afterwards I wiped my cheeks and sighed, “I needed that.” I physically felt better and my anxiety tank was less full. The next day was not as hard and I was able to get back to work. The book of Ecclesiastes says, “There’s a time to weep and a time to laugh,” and on that evening my body could have gone either way. I expected pain, but relief came through the joy of laughter. It was pure grace.

When widespread lockdown became inevitable, the content of the internet seemed to double overnight. We were bombarded with how to work from home, how to homeschool our kids, keep up with friends, stay close to God, keep ourselves busy, but not too busy, and how to sew our own mask so we don’t die. It was overwhelming: our existing responsibilities got harder and we had to figure out which new resources were helpful, read them, and put them into practice.

We’ve been put into impossible situations with less options and support than ever, and keep receiving a message of “You’ve got this.”

As long as I believe a magic technique exists to maintain last year’s version of life, I’m headed for a crash like the ones we see in Jesus’ parable of The Prodigal Son. When I feel like I’m pulling my weight, that my efforts are going unrewarded, I share the older brother’s resentment and bitterness. On days when I’m clearly falling short of all the standards, I spiral into a younger brother crash of guilt and shame.

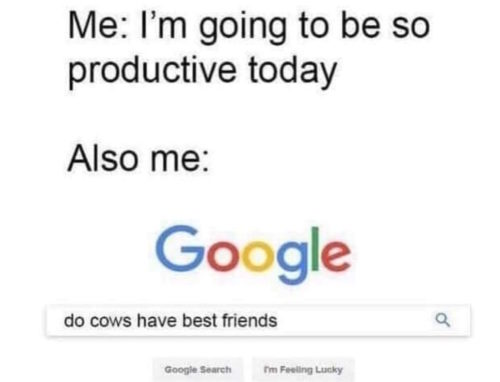

Enter humor. Alongside the hustle content, we’ve been treated to funny memes reminding us that we’re all drowning. The ambitious schedules for the new working-parent-teachers were updated to include time blocks for crying and Peppa Pig. We’ve joked about how slowly time is passing, how bad we are at doing nothing, and how Chili’s is trying to comfort us into buying fajitas.

This laughter brings relief. Our inner older brother is reminded “This situation is absurd and success is impossible.” Our inner younger brother is reminded, “You’re not alone.”

The relief of humor doesn’t come at the top but at the bottom. It’s the relief of remembering that we’re all broken people in a broken world. Despite our best intentions, we can’t help but make a mess of things. Even in our best efforts, we run up against absurd, random, irrational forces. There are many ways to relearn this lesson, most of which involve breakdowns, serious articles, and global pandemics. Laughter is more gentle, a recalibration that comes through joy.

Like everyone else, comedians are feeling the massive disruptions to our personal and professional lives. Like everyone else, we feel pressure to bring relief. People are saying things like, “We need art right now. We need to laugh right now.” We’re drowning and feel like we need to be a lifeboat. And now we have to try without a key essential worker: the live audience. The Covid-19 versions of late night and SNL have been interesting but off. The performers are still talented and delivering lines by the same professional writers, but you can feel a dip in rhythm and energy. They love and miss their audience. Like many of us, they wouldn’t have applied for their current job if they knew it’d be like this.

If you’re a comedian, you’ve been put into an impossible situation with impossible expectations. You can’t do this, and you’re not alone.

But even before this, the burden was always on you to figure out what that relief looks like. I teach comedy writing classes, which are great for certain things, like giving you structure to clarify ideas and a supportive space to develop your voice. Lifting burdens? Not so much. You’re given one moral rule, “Punch up, don’t punch down,” but it’s on you to know up from down to begin with.

Some attempts at relief look like a comily, and others look like a fire-and-brimstone sermon. This second approach can actually ramp up our anxiousness by keeping us in a state of threat. In her book, Irony and Outrage, professor and improviser Dr. Dannagal Young says, “humor appreciation requires a willingness to enter ‘a playful mode.’ If you feel threatened or aggrieved, if your ego is involved, if your empathy is activated, you will be less willing – and able- to operate in a playful mode.” Fear and play can’t co-exist.

Writing about shifts in comedy under the Trump presidency, Dr. Young writes that left-leaning comics at times “exited the state of play and began adopting some of the tropes of outrage.” By adopting alarm and moral seriousness, some comics have looked a lot like the outrage pundits critiqued by Jon Stewart and his disciples. Ironically, this can keep audiences from entering a state of play and experiencing the unique relief of laughter.

Even when an audience does laugh, it doesn’t necessarily mean relief is happening. It’s not cathartic if others are laughing about your gender, race, sexuality, religious beliefs, political convictions, physical appearance, level of ability, or accent. And ultimately it’s not relief for those who do the condescending joking and laughing. It’s a classic older brother move, clinging to a belief that you and your world are fine, and it’s those people over there that are making a mess of things. Maybe the laugh feels good, but then you have to keep being normal, keep blaming scapegoats, and keep being better than everyone else. It’s exhausting.

Ten days after my Colbert catharsis, I finally had my anxiety attack. The relief was limited and temporary. During lockdown I’ve needed daily recalibration, and it’s come from comforting words, serious articles, novels, playing with my kids, and every emotion from Pixar’s Inside Out. This relief is also limited and temporary.

For ongoing, comprehensive relief, we need a gracious father who loves us despite our big brother resentment and little brother shame. We need a priest that understands the impossibility of the human situation and has a godlike ability to do something about it.

That doesn’t make earthly, lesser relief less good. It was good when Stephen Colbert brought Anderson Cooper to tears talking about suffering, and it was good when he brought me to tears joking about CATS. A time to weep and a time to laugh. Each form of relief is its own kind of gift, and when we embrace our limits we’re free to let our jokes be jokes and our sermons be sermons.

As previously discussed here, writer Sam Anderson recently had a “religious” experience at a comedy event. He says the crowd was rolling in “sustained explosions of belonging and joy….We were one crowd, united in isolation, together in a great collective loneliness that — once you recognized it, once you accepted it — felt right on the brink of being healed.”

This relief came at a Weird Al concert. And it didn’t come in a sermon between songs, but during the singing of the 1996 hit Amish Paradise. The fascinating New York Times profile of Weird Al Yankovic paints a picture of a man who was never cool enough, whose iconic nickname was an insult from his college days. His ridiculous music is a joyful invitation, or as Anderson puts it, “a pulse, a signal, and these were the people it drew: the odd, the left out.”

This is good, priestly work in a hurting world.

COMMENTS

Leave a Reply