I had a picture of my ass posted to a social media app called Gaggle a couple months ago. Taken and uploaded anonymously by a student of mine while I annotated a text at the front of the class, the image had been doctored to include the word “booty,” superimposed across my derrière. Needless to say, I had a little chat with the intelligent young man who decided to post this “anonymous” picture from his assigned seat in what the picture’s background clearly indicated was my 5th period class. But what became clear to me (aside from the unsettling fact that a good number of my students had taken a moment to consider the junk in my trunk) was why this student posted this image in the first place; he was playing with his identity, in search of the magical combination of brains, brawn, and balls that will land him the role in the high school narrative that he wants most: a character of worth and value. He so desired to feel worthy of love and belonging that he allowed this emotional need to override any warning being sent by his prefrontal cortex to perhaps stop and think before snapping that photo.

I had a picture of my ass posted to a social media app called Gaggle a couple months ago. Taken and uploaded anonymously by a student of mine while I annotated a text at the front of the class, the image had been doctored to include the word “booty,” superimposed across my derrière. Needless to say, I had a little chat with the intelligent young man who decided to post this “anonymous” picture from his assigned seat in what the picture’s background clearly indicated was my 5th period class. But what became clear to me (aside from the unsettling fact that a good number of my students had taken a moment to consider the junk in my trunk) was why this student posted this image in the first place; he was playing with his identity, in search of the magical combination of brains, brawn, and balls that will land him the role in the high school narrative that he wants most: a character of worth and value. He so desired to feel worthy of love and belonging that he allowed this emotional need to override any warning being sent by his prefrontal cortex to perhaps stop and think before snapping that photo.

In his first book, New Clothes: Putting On Christ and Finding Ourselves, John Newton (to whom I just happen to have the privilege of being married) writes on our own Christian identity, and his ideas gave shape to my own as I have ruminated on this particular student’s actions, as well as all of my students, both current and future. Not unlike the story of Babel in Genesis 11, high school students (and many adults, at that) run about clamoring to make a name for themselves, a “shining image that [they can] take with [them] into the world” in order to feel worthy of love and belonging (121). A part of developing this image is looking about for a label, a name; “Someone or something must give us ‘a name’” (108). My students think, “Well, where shall I turn to find a new name? To whom shall I look for this identity, this sense of worth?” It seems logical that they would look around first, look at the context, the world in which they find themselves. They look at the narratives enveloping their high school culture, comparing their own identities to those around them, particularly those who are successful in claiming a valuable role in the most important script of all: high school.

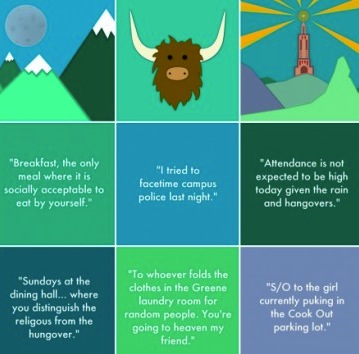

As James Bryan Smith explains in The Good and Beautiful God: Falling in Love with the God Jesus Knows, “There are cultural narratives that we learn from growing up in a particular region of the world. From our culture we learn values (what is important, who is successful) in the form of stories and images.” The stories and images that bombard our high school students today are the stories and narratives of Facebook, Instagram, Pinterest, Yik-Yak, Gaggle, Vine, Snapchat, Whisper, etc. etc. etc. They are learning what is important and who is successful primarily not from home or from their parents or from church but from social media, the number of “likes” their pictures garner, the number of followers or “friends” they have on their feeds. The narrative they absorb is that their worth depends on X. They are imprisoned by the script they think they must follow to be found valuable. The actors (my students, and many of us, as well) use whatever agencies they have available to them to create the meaning that seems the most valued in their world. Showing cleavage gets me more likes? Taking a selfie with my new car in the background proves my wealth? People like it when I say something shocking, even if it’s hateful? I can make my skin look a certain way just with a filter? Social media has become their “functional god, [their] religion, and the thing [they] bind or connect [their] hearts to” in search of a name (109). Ironic, isn’t it then, that students have recently gravitated towards anonymous social media apps because of the very lack of a name requisite? The surge of these particular social media apps such as Gaggle and Yik-Yak complicates our students’ search for an identity even further. Without feeling restricted, students look to these apps for a momentary high, a fleeting pat on the back for being funny or outrageous or coy or sexy or downright shocking. But it does nothing to help them in their quest for a name.

As James Bryan Smith explains in The Good and Beautiful God: Falling in Love with the God Jesus Knows, “There are cultural narratives that we learn from growing up in a particular region of the world. From our culture we learn values (what is important, who is successful) in the form of stories and images.” The stories and images that bombard our high school students today are the stories and narratives of Facebook, Instagram, Pinterest, Yik-Yak, Gaggle, Vine, Snapchat, Whisper, etc. etc. etc. They are learning what is important and who is successful primarily not from home or from their parents or from church but from social media, the number of “likes” their pictures garner, the number of followers or “friends” they have on their feeds. The narrative they absorb is that their worth depends on X. They are imprisoned by the script they think they must follow to be found valuable. The actors (my students, and many of us, as well) use whatever agencies they have available to them to create the meaning that seems the most valued in their world. Showing cleavage gets me more likes? Taking a selfie with my new car in the background proves my wealth? People like it when I say something shocking, even if it’s hateful? I can make my skin look a certain way just with a filter? Social media has become their “functional god, [their] religion, and the thing [they] bind or connect [their] hearts to” in search of a name (109). Ironic, isn’t it then, that students have recently gravitated towards anonymous social media apps because of the very lack of a name requisite? The surge of these particular social media apps such as Gaggle and Yik-Yak complicates our students’ search for an identity even further. Without feeling restricted, students look to these apps for a momentary high, a fleeting pat on the back for being funny or outrageous or coy or sexy or downright shocking. But it does nothing to help them in their quest for a name.

All of this identity-seeking depends entirely on context. As my husband writes in New Clothes, “When it comes to our identity, context is everything. We only have an identity in a context” (107). The problem, of course, is that every high school student longs to feel worthy and valuable, but they’re playing with their sense of self within the wrong context, a narrative that shifts and shakes and has no real power to clarify or satisfy. The context of social media simply isn’t providing the right environment for their formation. They don’t know, or aren’t being told or encouraged, to look for a better context from which to pull a sense of self. Most are not looking to the Bible, “the context where God invites us to discover who we [already] are” (136). My students need to hear and to believe that they already have a name. Beloved. Child. Heir. And that they don’t have to use an Instagram filter to claim it.

COMMENTS

Leave a Reply