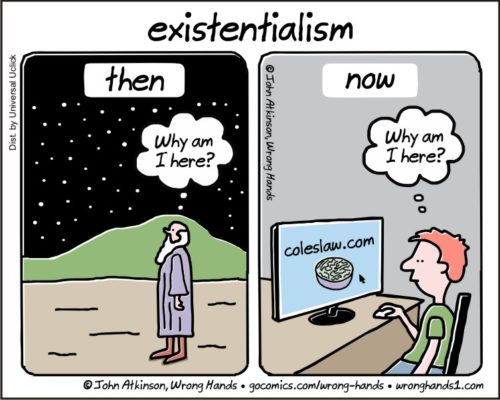

A week ago my father asked me, presumably because I was the only suitable philosophical authority within a few miles, what “Existentialism” is. Being the word-merchant that I am, I deftly replied, “uh…well, it was kind of started by Kierkegaard — though it’s not explicitly Christian — and it deals with big questions, like, um, well, you know, the big ones! Who am I, how does one live an authentic life, what is an individual — that sort of thing. Yeah!” I think I eventually threw in some stuff about Dostoevsky too. Needless to say, it wasn’t pretty.

Despite my valiant defense, Existentialism often gets a bad rap within the church. Its persistent focus on the individual is construed as a progenitor to contemporary, robust individualism that is antithetical to genuine ecclesiastical community; in some ways it might be. But the Existentialists, Kierkegaard especially, were not necessarily individualists as we know them. They simply acknowledged that the fundamental experience of life was indeed individual — that is, literally, unable to be divided. For though the human experience may be conglomerated through community, it cannot be dissected past the discreet, indivisible, single human consciousness.

Despite my valiant defense, Existentialism often gets a bad rap within the church. Its persistent focus on the individual is construed as a progenitor to contemporary, robust individualism that is antithetical to genuine ecclesiastical community; in some ways it might be. But the Existentialists, Kierkegaard especially, were not necessarily individualists as we know them. They simply acknowledged that the fundamental experience of life was indeed individual — that is, literally, unable to be divided. For though the human experience may be conglomerated through community, it cannot be dissected past the discreet, indivisible, single human consciousness.

We might say that we have “walked in another’s shoes” or “seen life through another’s eyes,” but no one insists that these phrases are anything more than expressions of empathy, and somewhat banal at that. I will only see life through my own eyes and walk in my shoes, no matter how well I “know” someone else. Even the “one flesh” mandated by marriage does not merge two people together into one; it simply consists in two people progressively becoming so emotionally and morally united that they are effectively indivisible. Kierkegaard puts it this way: “Custom and use change, and any comparison limps or is only half truth; but eternity’s custom, which never becomes obsolete, is that you are a single individual, that even in the intimate relationship of marriage you should have been aware of this.” Though relationships like marriage often prove indelible conduits for companionship amid loneliness and solace in suffering (grace!), they cannot literally unite you to another person, binding wills together. For richer or poorer, in sickness and in health, you are still you, with all your personal baggage and anxiety and sin. As K makes clear, “Eternity does not ask whether you brought up your children the way you saw others doing it but asks you as an individual how you brought up your children.”

This is not to deny the profound and pervasive effects of a bunch of stupid people gathered together, such as in systemic or communal injustice. But it is to say that the sin perpetrated within a certain community is not the fault of (though it may be exacerbated by) the community itself — after all, what does it even mean to attribute moral culpability to a social abstraction? Rather, it is the collective fault of the individuals constitutive of a harmful corporate system, unwitting or intentional. The Third Reich was evil, but it did not kill Jews–people did. Slavery was deplorable, but it did not own people. People owned people.

Nor is this to say that other institutions — families, churches, friendships — are bereft of grace. Quite the opposite, in fact. It certainly seems like community is one of the central ways in which God confers grace to human beings. Consider Israel or the church, for example. But, though the community is, at times, a receptacle of grace, we must not confuse our terms. The community is not primarily a recipient of grace but rather a means of grace through which God gives grace to individuals. In the same way that the community per se cannot (or should not) itself shoulder guilt, nor does it need forgiveness. The community, like its constituents, might need redemption, but only its constituents require forgiveness.

And just as we cannot depend on relationships or communities to bear our sin or impart grace, neither can we depend on mere generalities or doctrines to do likewise. The doctrine of original sin informs; it does not convict. The doctrine of the atonement explains, but it does not forgive. No matter one’s penchant for dogma or aptitude at theologizing, he or she will never come to know the depths of their own sin or of the looming magnitude of grace without a (as much as I hate the word) personal confrontation with both the reality of their sin and the news of the gospel.

Those who gather as a church for worship often already know and confess that they are sinners in need of grace. What they need, and what those need who do not feel themselves to be sinners, is the careful, gentle, yet direct exposure of their sins, corporately and individually: not merely the faults of our society or problems in our culture or merely sinful activities … What those gathered to worship need to hear is the root sins of self-seeking, pride, lust, envy, and greed by which we deny God and mistreat one another. The “practical atheism” which infects our daily lives without our seeing it must be exposed and judged so that we see afresh precisely what it is that Christ has done for us.

It was this same sentiment that propelled Martin Luther to implore: “Who is this ‘me’? I, wretched and damnable sinner, dearly beloved of the Son of God. Did the Law ever love me? Did the Law ever sacrifice itself for me? Did the Law ever die for me? On the contrary, it accuses me, it frightens me, it drives me crazy.” Luther — though an ardent advocate of original sin — more importantly had an intimate encounter with his own “practical atheism,” effecting a profound and intractable dread that drove him crazy. When confronted by the indifference of the Law, the self simply faded into a mist of sinful insignificance. “If I keep looking at myself,” he wrote, “I am gone.”

Peter did not crash to his knees in a fishing boat to cry “Go away from me, for humans are sinful as explained in the doctrine of original sin!” No — Peter begged the Lord depart from him because he, at the level of his very being, was misguided and depraved, and he knew it. I always wondered why Paul referred to himself as “the chief of sinners” (post-conversion, no less). After all, though he was a pretty bad guy at one point, there were certainly some worse people out there. However, I realize now that it’s because he was himself and he knew himself. He acknowledged that the worst person he could know was himself.

Peter did not crash to his knees in a fishing boat to cry “Go away from me, for humans are sinful as explained in the doctrine of original sin!” No — Peter begged the Lord depart from him because he, at the level of his very being, was misguided and depraved, and he knew it. I always wondered why Paul referred to himself as “the chief of sinners” (post-conversion, no less). After all, though he was a pretty bad guy at one point, there were certainly some worse people out there. However, I realize now that it’s because he was himself and he knew himself. He acknowledged that the worst person he could know was himself.

Nonetheless, one of the most effective ways in which we might come to recognize our own sin is through another, whose perspective is not obscured by self-pity. For instance, consider Nathan’s confrontation of David after his promiscuity with Bathsheba, wherein the vexed prophet shrieked at David: “You are the one!”, prompting the obstinate king to eventually lament, “My sin is ever before me!” This admission, notably, is not simply a list of iniquities committed, but a deep and profound acknowledgement of a fundamental sinful state. Kierkegaard again: “Anyone who wishes to learn the art of sorrowing over your sins will certainly discover that the confession of sin is not merely a counting of all the particular sins but is a comprehension before God that sin has a coherence in itself.”

What an arresting thought — face to face with a holy God, confessing that we are coherently sinful. “Wretched man that I am! Who will deliver me from this body of death?” we cry with Paul. But, he responds, “Thanks be to God through Jesus Christ our Lord!” The incomprehensible depth of our own sin also leads us to the greatest consolation: that Christ has united himself, as no other spouse or friend possibly could, to us, becoming our sinful selves and dragging them kicking and screaming up to Golgotha.

Faith connects you so intimately with Christ, that He and you become as it were one person. As such you may boldly say: “I am now one with Christ. Therefore Christ’s righteousness, victory, and life are mine.” On the other hand, Christ may say: “I am that big sinner. His sins and his death are mine, because he is joined to me, and I to him.”

— Luther

The doctrine of atonement didn’t absolve our sin and destroy our death — an individual did. Nor did this individual hang on the cross to establish the doctrine of justification or so that Paul could say “one died for all.” He did not give himself to save the world or nations or even the church. He hung on the cross for me and for you and for your mother-in-law and for the baby wailing away in 18C. He died for persons.

Driving through the cozy sapphire mountains of West Virginia with my dad (see above), we had a conversation that, Lord knows, would only interest anyone whose birthday was roughly prior to 1967. (In my defense we were going on hour 10.) Utterly captivated, I asked, “Wait — so you use ‘their’ with ‘all’ but ‘his’ or ‘hers’ with ‘everyone’?”

Driving through the cozy sapphire mountains of West Virginia with my dad (see above), we had a conversation that, Lord knows, would only interest anyone whose birthday was roughly prior to 1967. (In my defense we were going on hour 10.) Utterly captivated, I asked, “Wait — so you use ‘their’ with ‘all’ but ‘his’ or ‘hers’ with ‘everyone’?”

“Yep. ‘Everyone’ isn’t plural,” he clarified as he shifted into fifth. “Think about it: everyone — every one — person has ‘his’ lunchbox. Not their lunchboxes.”

It finally clicked, and with it, something larger (and not absurdly boring) shifted slightly in me. God does not merely offer forgiveness to everyone, as if he were some kind of omnipresent cosmic security blanket, but to every-one. Every one, single person who has ever sinned or fallen short has been individually presented with overflowing grace. His crimson blood has washed over each specific misdeed and all its disgusting details. Every subtle flirtation with or outright embrace of sin has been caught, acknowledged, and “re-cognized,” as Capon would say, as an object of forgiveness and source of glory — grace as scrupulous and pedantic as grammar. God doesn’t deal in plurals.

Who knew some possessive pronouns could be so fun?

Nietzsche (who wasn’t technically an Existentialist, but who’s counting?), in the wake of the “death of God,” suggested that the most basic moral and ontological reality was necessarily individual and nothing more — objectivity thrown out with the bathwater. And thus, any Bible-believing Christian worth their salt sneers. Objective truth (or, “Truth with a capital T”) is our thing! And Truly, the ultimate essence of Christian Existentialism is not the repudiation of the objective but rather its absolute acceptance. It is not a dismissal of the question “What am I?”, but a hope that there is something that is so radically other that it doesn’t really matter. Amid cogito and tabula-rasa and ubermensch, it is the concession that one really is no more than a momentary ripple in the ocean of existence but also that this tiny blip of selfhood is now made real and meaningful by something altogether outside it.

We are no longer then, as Sartre (one of the more moody Existentialists) opined, “the sum of our actions.” His conjecture leads us to one of two conclusions: first, that we are somehow able to will ourselves to make the correct decisions conducive to a good life — in which case the outlook is quite bleak — or second, that we can’t will ourselves to perfection, in which case it seems we’re pretty screwed. We are instead caught up in an absurd reality in which God has had a quite fortunate lapse of good judgement — forgiving the unforgivable — and considers me as Christ, the one who loved me and gave himself for me. Luther concludes:

Read the words “me” and “for me” with great emphasis. Print this “me” with capital letters in your heart, and do not ever doubt that you belong to the number of those who are meant by this “me.” Christ did not only love Peter and Paul. The same love He felt for them He feels for us. If we cannot deny that we are sinners, we cannot deny that Christ died for our sins.

There. Christian Existentialism in a nutshell. I think my dad will get the gist.

COMMENTS

3 responses to “Grace for ME: Kierkegaard, Sin, and the Self”

Leave a Reply

Love this, August! Especially this part: “God does not merely offer forgiveness to everyone, as if he were some kind of omnipresent cosmic security blanket, but to every-one. Every one, single person.” Thanks for an engaging read.