Part 1

The end is near, and it’s coming to a theater near you, or right into your own living room. I first started paying close attention to the regularity of end-of-the-world scenarios in popular culture—especially in film and television—with the 1998 movies Deep Impact and Armageddon. Both involved the threat of a history-ending meteorite strike (a comet or an asteroid, respectively). Deep Impact attempted a serious dramatic look at the political repercussions and human pathos of an impending world-ending disaster; Armageddon (whose title betrays a serious lack of familiarity with the biblical book of Revelation) was one of those cinematic amusement park rides. Both films were actually “apocalypse-averted-by-human ingenuity and pluck” stories, with heroic, self-sacrificial efforts destroying the incoming mountains of rock and ice (or mostly so, in Deep Impact). This past summer—the apocalypse movie season—I saw two apocalypse-themed movies, Tomorrowland and Terminator Genisys, both of which are also apocalypse-averted stories; and also saw San Andreas, a mega-disaster, almost-apocalypse (sort of 2012 lite), and another cinematic roller coaster. I have yet to catch Mad Max: Fury Road. Next summer, the Marvel comic book universe will do the end of the world with X-men Apocalypse.

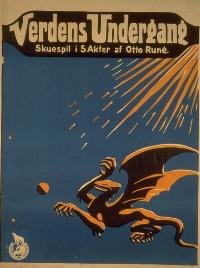

Of course, popular fascination with films about the apocalypse is almost as old as Hollywood. The first end-of-the-world movie was the appropriately named 1916 Danish film, The End of the World (Verdens Undergang), featuring a near-miss by a passing comet which triggers worldwide natural disasters and social upheaval. The “doom-from-space” trope got a re-start in When Worlds Collide (1951), with the planet-killing heavenly body being a rogue star on a collision course with Earth. This time the plucky humans build a “space ark” to ferry a few lucky lottery winners to the habitable planet orbiting the rogue star. The asteroid apocalypse concept then lay relatively dormant until Deep Impact and Armageddon.A variation of the doom-from-space scenario, the “alien invasion apocalypse”, got a classic start in 1953 with the original film version of H.G. Wells’ novel The War of the Worlds. The Spielberg-helmed 2005 remake had spectacular special effects, but for my money the original is a better story, as well as more fun to watch. The sub-genre reached blockbuster status with Independence Day (1996), which features a horde of alien barbarians, roaming the galaxy like interstellar Visigoths to plunder planets for their resources.

Of course, popular fascination with films about the apocalypse is almost as old as Hollywood. The first end-of-the-world movie was the appropriately named 1916 Danish film, The End of the World (Verdens Undergang), featuring a near-miss by a passing comet which triggers worldwide natural disasters and social upheaval. The “doom-from-space” trope got a re-start in When Worlds Collide (1951), with the planet-killing heavenly body being a rogue star on a collision course with Earth. This time the plucky humans build a “space ark” to ferry a few lucky lottery winners to the habitable planet orbiting the rogue star. The asteroid apocalypse concept then lay relatively dormant until Deep Impact and Armageddon.A variation of the doom-from-space scenario, the “alien invasion apocalypse”, got a classic start in 1953 with the original film version of H.G. Wells’ novel The War of the Worlds. The Spielberg-helmed 2005 remake had spectacular special effects, but for my money the original is a better story, as well as more fun to watch. The sub-genre reached blockbuster status with Independence Day (1996), which features a horde of alien barbarians, roaming the galaxy like interstellar Visigoths to plunder planets for their resources.

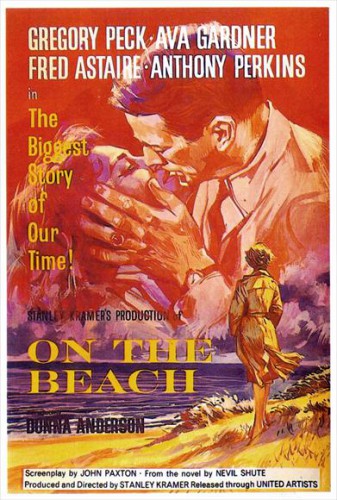

My first apocalyptic film experience was Stanley Kramer’s 1959 nuclear disaster epic On the Beach (I saw it nearly a decade after its first release, as the weekend entertainment at the private boys school I attended in the late 1960s). Based on Nevil Shute’ book, On the Beach is a “truly-the-end-with-nothing-after” apocalypse. Set in 1963, the story begins after a nuclear war has devastated the entire northern hemisphere, and lethal radioactive fallout is now spreading to the last outposts of mankind in Australia and New Zealand. Eventually the fallout reaches southern Australia and one-by-one the story’s main characters, to avoid the agony of radiation sickness, commit suicide with government distributed pills. On the Beach was the first cautionary tale of word-ending atomic cataclysm.

The same year On the Beach came out, nuclear apocalypse was turned into a parable about disarmament and racial reconciliation with The World, the Flesh, and the Devil. The budding genre reached a climax in the made-for-television movie The Day After (1983), the highest-rated television film ever, watched by over 100 million people. The movie begins with a geopolitical drama between the United States and the Soviet Union, culminating in a full-scale nuclear war. The second half is a grim “slice-of-post-nuclear-apocalypse-life” story, following the tragic fates of the few survivors in and around the small city of Lawrence, Kansas.

The “cautionary end-of-the-world tale” genre added the “environmental apocalypse” in 1972 with Silent Running, in which an unspecified disaster has destroyed all plant life on Earth. Saturn-orbiting “bio-domes” hold the last botanical remnants, for scientific study and possible re-forestation in the future. In Soylent Green (1973) the problem is run-away overpopulation and industrial pollution. The primary food source, a green wafer called Soylent Green produced by the Soylent Corporation, is made–spoiler alert–of processed human remains. The threat of global warming made its apocalyptic debut in 1993 with the television mini-series The Fire Next Time. Waterworld in 1995 continued the trend, conjecturing a planet submerged in H2O, while The Day After Tomorrow (2004) took the ice age route.

The most popular world-ending scenario for the last few years has been the “zombie apocalypse”. The literary and film beginnings of the zombie have deeper roots, but the idea of a world overrun by the “undead” began with the novel by Richard Matheson, I Am Legend (1954). In Matheson’s book one man remains unaffected after a non-specified disease with vampire-like symptoms has infected everyone else on the planet. Matheson’s book was made into a movie in 1964, The Last Man on Earth, with Vincent Price as the main character and then twice more with The Omega Man (1971) and I Am Legend in 2007. Director George Romero admitted that he borrowed heavily from Matheson’s book in his 1968 film, Night of the Living Dead (1968), which introduced an undead that craved and consumed human flesh. Danny Boyle turned in an inventive riff on the genre with 28 Days Later in 2002. Then there’s Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, Suzanne Collins’ The Hunger Games, Brad Pitt’s World War Z, the list goes on and on.[1]

As of this writing, over 250 end-of-the-world movies have been produced, with more than 100 appearing since 2000. The pace of apocalyptic drama shows no sign of slowing down. Believe it or not, the number of apocalypse-themed movies from 2000 to 2009 doubled over the previous decade, and is on pace to double again by the end of this decade. Why? One reason is that the purveyors of popular culture—the artists, the writers, the filmmakers—are always mining the cultural deposits bequeathed by Western Civilization to cobble together compelling stories to draw audiences and make money. One of the larger deposits, from the Judeo-Christian tradition, is the linear view of history, with its one-directional timeline leading to a definite ending of history; the End Time, Judgment Day.

As of this writing, over 250 end-of-the-world movies have been produced, with more than 100 appearing since 2000. The pace of apocalyptic drama shows no sign of slowing down. Believe it or not, the number of apocalypse-themed movies from 2000 to 2009 doubled over the previous decade, and is on pace to double again by the end of this decade. Why? One reason is that the purveyors of popular culture—the artists, the writers, the filmmakers—are always mining the cultural deposits bequeathed by Western Civilization to cobble together compelling stories to draw audiences and make money. One of the larger deposits, from the Judeo-Christian tradition, is the linear view of history, with its one-directional timeline leading to a definite ending of history; the End Time, Judgment Day.

Of course, pop culture apocalypses are never fully true to the Judeo-Christian tradition (the few faith-based efforts fail, in my opinion, to convey either accurate theology or a serious engagement with the intersection of God’s providence and geopolitical reality). The end of the world is almost never a divine judgment or even a destiny descending from a transcendent realm; never a heaven-brought or God-wrought reality. God, in fact, is conspicuous by his absence in the vast majority of pop apocalypses. Instead, the end of the world is threatened by man-made, natural, or alien-invasion disasters. And, almost always, the end of the world can be, and usually is, averted by human imagination and determination. The almost-end-of-the-world becomes the occasion to congratulate ourselves for our indomitable “human spirit”. Even the few films with genuinely world-ending scenarios, such as On the Beach, are only cautionary and never actually intended as “prophetic”. The world could end this way, they want to say, if we don’t mend our ways and alter our course. But of course we can mend our ways; we can overcome adversity; we will stop the world from ending: “Today, we are canceling the apocalypse!,” is the exuberant outburst from one of the main characters in 2013’s Pacific Rim (an alien invasion apocalypse).

As well as a quintessentially American celebration of human optimism, know-how, and will at the core of many apocalypse films, some end-of-the-world stories exercise a cathartic effect on audiences, like the effect of Greek tragic drama, according to Aristotle. This is especially true of the serious “doom from space” movies, like Deep Impact, and the biological/zombie apocalypses that are more than gore-fests, like I Am Legend, The Last Ship or The Walking Dead. These films offer a vicarious, if somewhat superficial, cathartic purging of anxieties and fears—not wholly unrealistic ones—about cataclysmic natural disasters, epidemics, or NBC (nuclear-biological-chemical) terrorism. But this cathartic effect is fleeting, truncated, and artificial, much like the sense of danger and the adrenalin rush from the highly controlled “adventure” of an amusement park ride. What is more, contemporary Western—and particularly American—culture cannot abide tragedy for long, and even the end of the world must have a happy ending, or at least a few plucky survivors who bravely carry on, seeking redemption in the post-apocalyptic wilderness.

I can’t help but wonder if there is a deeper reason for the proliferation and popularity of apocalyptic stories and films. Could it be that we all have an inner awareness, a deep knowing that our history has its appointed conclusion, that the end of our story has already been written? After all, every major world religion embraces a story of the end of the world. Perhaps Jung would have called this part of our collective unconscious, but I think it is only just below the surface of our everyday lives. And it is perhaps no accident that the increase in the number of apocalypse-themed films in the past few decades has coincided with the rise of increasingly chaotic geopolitics. The rise of radical Islamic terrorism, Russian aggression in Eastern Europe, and North Korean and Iranian nuclear programs have certainly not damped down our sense of history hurtling towards a conclusion. This sense of the world’s ending regularly emerges in our cultural expressions, where, for many of us, the popular entertainment of movie-watching has replaced religion as the place where we communally remember and rehearse our shared symbols and archetypes. We look to movies and television—the way we used to look to the Church and worship—to tell us who we are and where we are going, even unto the end.

Popular entertainment can be diverting, sometimes in a good way. It can be deeply refreshing to turn aside from the world for a while and be entranced by the story-telling of a film. A good movie can also be engaging and enlarging, making us aware of things we did not know, or making us look at old things in new ways. This is true for some of the more thoughtful apocalypse movies. But even the best ones miss crucial points, especially the main points of what the “apocalypse” even means, and what the “end” of history actually brings.

“Apocalypse” doesn’t mean “end”; it literally means “unveiling.” It comes from the Greek New Testament term apokalypsis (άποκάλυψις). The Latin equivalent is revelatio; “revelation”. An “apocalypse” is an unveiling; something once hidden is now disclosed. The best-known such unveiling is the New Testament book of Revelation (in the original Greek, “Apocalypse”), which records a series of visions of the apostle John around AD 80 – 90. The book of Revelation is notoriously difficult to interpret—nearly everything after chapter three is symbolic—but it does describe a set of cataclysmic events leading to God’s final judgment of humanity. So it’s not surprising that “Apocalypse” has come to mean “end of the world”.

“Apocalypse” doesn’t mean “end”; it literally means “unveiling.” It comes from the Greek New Testament term apokalypsis (άποκάλυψις). The Latin equivalent is revelatio; “revelation”. An “apocalypse” is an unveiling; something once hidden is now disclosed. The best-known such unveiling is the New Testament book of Revelation (in the original Greek, “Apocalypse”), which records a series of visions of the apostle John around AD 80 – 90. The book of Revelation is notoriously difficult to interpret—nearly everything after chapter three is symbolic—but it does describe a set of cataclysmic events leading to God’s final judgment of humanity. So it’s not surprising that “Apocalypse” has come to mean “end of the world”.

But the end of our history—this history we now inhabit—is not the only thing revealed in the book of Revelation. The Apocalypse will also be the unveiling of true Reality; the way things really are, beyond all our illusions, delusions, and denials. We will be made to realize that our vision has been small and clouded; that there are infinite heights and boundless horizons to the meaning of our existence, welling up from the infinite depths of God’s love. There will be an end of the world as we know it, this world of suffering, disappointment, and death. But there will be “a new heaven and a new earth” after this world has passed away. Everything will be made new, “there will be no more death or mourning or crying or pain, for the old order of things has passed away”, and we will live with God (Revelation 21:1-5). Someone should make a movie about that.

[1] All this without mentioning the significant inroads that apocalyptic drama has made on the small screen, AMC’s The Walking Dead being just one prominent example.

COMMENTS

3 responses to “It’s the End of the World as We Know It: The Apocalypse in Popular Culture”

Leave a Reply

Interesting. The listing omits my personal fave – Robert Wise’s 1951 sparkling Science Fiction classic, The Day The Earth Stood Still (pointlessly and sluggishly re-made recently), in which humanity’s march to its own doom is at least interrupted by the arrival of a being seeking to bring a measure of equilibrium to madness, even if it costs his own life (that sounds familiar). With great performances by Michael Rennie and Patricia Neal, the drama uses a wonderful employment of world-wide disruption to warn humanity of what could be if it continues along its present reckless route to employing hugely destructive power.

Thanks for the feedback, Howard. I definitely agree with your comments about The Day The Earth Stood Still (original and remake). The film does get a mention in a previous post of mine on another theme in sci-fi films:(https://mbird.mystagingwebsite.com/2015/01/you-descended-from-the-stars-christmas-and-otherworldly-salvation/)

[…] the End of the World as We Know It: The Apocalypse in Popular Culture.https://mbird.com/religion/its-the-end-of-the-world-as-we-know-it-the-apocalypse-in-popular-culture/Bing image Lower Yellowstone Falls, Yellowstone National Park, […]