This week, we turn to an untitled story about Jesus Christ–you know, the stowaway on board the Hiroshima mission. To read along, go here.

“Pulp trash you say. But this is not entirely true …”

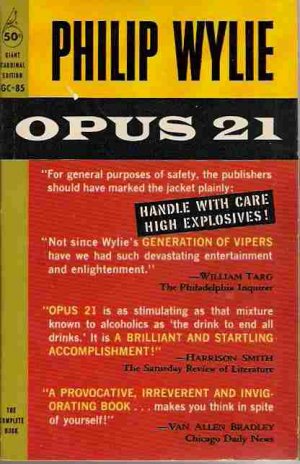

-John Small on Opus 21, Harvard Crimson, 1949

This story comes from a small chapter near the end of Philip Wylie’s exaggerated, disjointed sci-fi thriller, Opus 21. It’s political – perhaps a bit too political – but statements of the kind Wylie is making are part and parcel of the sci-fi genre. From post-apocalyptic scenarios, to dystopianism, to Ray Bradbury-esque encounters ‘of the third kind’ with aliens, science fiction often uses absurd, implausible scenarios to make statements about how or where or when the human race has gone wrong. Agree with Wylie’s politics or not, this story is a masterpiece of the genre.

This story comes from a small chapter near the end of Philip Wylie’s exaggerated, disjointed sci-fi thriller, Opus 21. It’s political – perhaps a bit too political – but statements of the kind Wylie is making are part and parcel of the sci-fi genre. From post-apocalyptic scenarios, to dystopianism, to Ray Bradbury-esque encounters ‘of the third kind’ with aliens, science fiction often uses absurd, implausible scenarios to make statements about how or where or when the human race has gone wrong. Agree with Wylie’s politics or not, this story is a masterpiece of the genre.

Alien encounters were among the first sci-fi stories written, and with good reason. The alien-encounter subgenre offers human beings a snapshot of a view outside of and beyond our own reality. Aliens meet humans, and we’re confronted with a new reality, one in which the author can judge the human race from the unbiased, objective standpoint of another, equally intelligent (or more intelligent/advanced) species. A classic example of this is Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse Five, in which Billie Pilgrim, the protagonist, learns that out of the thousands of sentient species in the universe, human beings are the only one that believes in free will (ha!). But that’s just an example of alien literature’s appeal: there is an Other who is judging and evaluating human civilization using criteria which are different from, and perhaps more valid than, our own.

The prototype for alien literature is, of course, religion. Religion has generally posited a set of otherworldly beings who offer a critique of humanity from a higher viewpoint than our own. Thus it is entirely appropriate, in Wylie’s tale, that Jesus Christ should show up on the Enola Gay during its bombing run on Hiroshima. Just as Huxley, Bradbury, and Orwell used more exaggerated versions of our civilization to critique the parts of it that we take for granted, so too Wylie has imaginatively used an outsider to human civilization to critique it. The person of Christ, in this tale, allows Wylie to offer a fresh take on the good guys’ victory in the largest war this planet has ever seen. Christ is the alien, the outsider, the Other, who shows up to question the existing way of doing things.

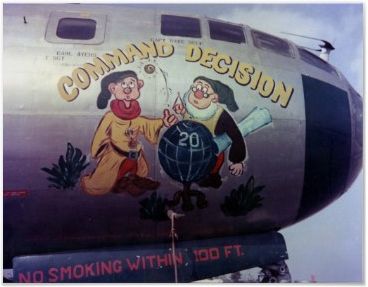

We have to admit that Wylie’s story lacks the sublime characterization and narrative subtlety of Joyce or O’Connor but, again, his political focus is appropriate for the revisionist-historical / science fiction genre. So we’ll be dealing more with the ideas and how he conveys them than with literary devices or strictly literary concerns. The problem, for Wylie, seems to be that we as a species have gotten a little self-obsessed with our (admittedly remarkable) aptitude for science. From his opening descriptions of the B-29 onward, we see a certain mechanization of society – extreme personifications of the aircraft and a corresponding mechanization of the humans who operate it. Science itself, however, is not Wylie’s target; his target instead is the intricate systems humans use to justify our actions.

The colonel prizes duty above all else, and his patriotism moves him to excitement about the mission and anxiety about any chance of it not going to plan. The scientist, though more dubious about the mission’s purpose, appeals to the descriptive mercilessness of nature as a permission for the same mercilessness in human affairs.

The scientist’s main flaw, according to his dialogue with ‘Chris’, is too much optimism about human capabilities. He claims that the atomic bomb has ended war by changing the strategic environment of global conflicts, arguing that too much is now at stake for another war to be fought (mutually assured destruction). Christ admits that the bomb has changed the environment of war, “but [it’s] not changed men.” Human nature, for him, is the destructive force in the world, and human nature cannot fix its own problems, no matter how intellectually or scientifically advanced we become.

The journalist, however, believes almost immediately because Wylie has used his profession to characterize him as an observer. He represents someone who doesn’t operate by human systems, but rather works outside of them and comments on them. He doesn’t have the same blockages as they do.

By human systems, I mean thoughts, ideas and institutions that we construct in order to give our lives structure and meaning. Again, the search for scientific truth and patriotism/nationalism are prime examples. These aren’t bad things in and of themselves, but they do hinder our receptivity to other sources of truth or meaning. Pride is artificial; we create certain opinions of ourselves or identities, but the most prideful people are often anxiety-ridden because our subconscious remembers that we are faking it, and we live in fear that these artifices will come crumbling down in an event of suffering, loss, impasse, or defeat. This is also a reason why more prideful people tend to be less receptive to criticism – the anxiety that accompanies our artifices puts us on high alert to any threats to our self-justifying identities.

The colonel and scientist here are on ‘threat level red’ when they find the random extra passenger on their plane. Their systems and identities don’t allow for Chris, who presents a compromise of mission security (the colonel nervously thinks of the demotions that will ensue after they land with Chris) and an alternative to the scientist’s quantifiable, utilitarian truth. Again, Wylie’s being political, but part of the message is apolitical – conservatives and liberals, Jews and Greeks, rich and poor all found equally little room for Chris’s message in the first century CE. When threatened with the gratuity of the alien, for whom they have no categories, the men balk.

Wylie contraposes gratuitous moral demand (‘thou shall not kill’ and ‘turn the other cheek’) with gratuitous violence. The bomb may indeed have been justifiable as a way to save more lives in the long run (“simple arithmetic!”, the scientist says), so it’s arguably not immoral in the slightest from a utilitarian ethics of greatest good for the greatest or from utilitarianism’s nationalistic cousin (greatest good for the greatest number of people on our side). But Wylie presents us with a more primal, experiential ethics in which there is still a moral horror to be faced and reckoned with. Though human systems may justify something, there’s an underlying gratuitous moral imperative of the kind that Wylie’s protagonist brought out in Matthew 5.

Again, this isn’t to take a stance on political ethics, just war theory, etc. It’s just to say that from an experiential perspective, Hiroshima and Nagasaki were utterly tragic, even if they were necessary. Sci-fi can use exaggerated situations like this one to highlight the experiential, literary dimension of ethics where even necessary tragedies are no less tragic. His closing terms of “Horror and Shame” and “Naked Sorrow” embody this idea.

Even when systems are correct – even if using the bomb was the right call – the deeper point of Wylie’s story is that human systems function as barriers to both Law and grace. There’s a more fundamental dimension to life than these systems, which is the dimension of interpersonal, emotional human experience, and this dimension is where Chris(t) usually works. It’s a great strength of storytelling to approach this dimension in an especially acute way, and science fiction in particular can bring categorical moral imperatives to light in the same way it can provide an outsider perspective on human institutions. In asking us to reckon with moral law, Wylie deconstructs these systems and places us, like the journalist, in the position of observers and commentators which, ideally, is the position of receptivity. Once our identities have been rattled (second use of the Law, in Lutheran terms), there’s an opening of space in which grace can arrive. Even if the story’s action was justifiable, we can still condemn a world in which mass slaughter would be necessary. Recognizing this necessity, in some small way, brings us to the place of hopelessness – the place of the woman caught in adultery, of the apostle Peter’s ‘to whom else can we go?’, of the man hanging on the cross beside Jesus, recognizing that ‘indeed we have been condemned justly.’ Strangely enough, it’s not a bad place to be.

Next week, we transition from World War Two to PTSD with Ernest Hemingway’s classic “Big Two-Hearted River.”

COMMENTS

Leave a Reply