Much like the nation of Greece, the season of Lent is characterized by “austerity measures.” And while such devotion can be beautiful, Lenten observance can also border on piety for piety’s sake, or what we might call works righteousness. Please do not misunderstand me: I enjoy and value the season. Who of us wouldn’t benefit from setting aside time to reflect on the grace and mercy of God (and our need to repent)?

Much like the nation of Greece, the season of Lent is characterized by “austerity measures.” And while such devotion can be beautiful, Lenten observance can also border on piety for piety’s sake, or what we might call works righteousness. Please do not misunderstand me: I enjoy and value the season. Who of us wouldn’t benefit from setting aside time to reflect on the grace and mercy of God (and our need to repent)?

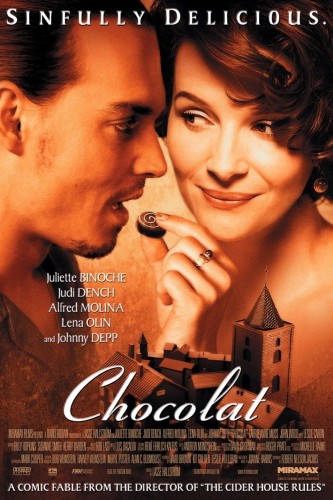

The tension between the need for mercy that defines Lent (in theory) and the works righteousness with which it has all too often become synonymous is the theme of the film Chocolat (2000) starring Johnny Depp, Juliette Binoche, Judi Dench, et al. Simply put, Chocolat is as pure a Law and Gospel film as one is likely to find. The legalism of a small, highly religious French town finds itself at odds with the graciousness of a beguiling new arrival named Vianne, who causes a scandal by opening a chocolaterie (chocolate shop) at the beginning of Lent. The mayor of the town, Comte Paul de Reynaud, played by Alfred Molina, exclaims, “The sheer nerve of the woman … opening a chocolaterie just in time for Lent. The woman is brazen.” Indeed, the Comte personifies the town’s self-righteous pietism, and he makes it his mission to run Vianne out:

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q4-XxWqSgH8&w=600]

If the Comte personifies legalism, then Vianne personifies Grace. At least, she is the Christ figure of the film. Not because she is innocently martyred (she isn’t), but because she treats everyone she meets in the town as righteous despite their obvious flaws. In effect, she forgives them their sins, and her love for them (manifested in the free gift of chocolate) has a transformative effect. Just about everyone who encounters Vianne changes, for example, Armande, a grumpy and heretofore unloved elderly woman:

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yuU67Mv4bFA&w=600]

But just as Vianne begins to win some of the locals over with her chocolate and charm, another “bigger problem” comes to town. A band of gypsies led by Depp’s character Roux, who call themselves “River Rats,” arrive, ruffling the feathers of the citizenry, the Comte chief among them. The townspeople equate Christianity with morality, as evidenced not only by their approach to Lent but also their reaction to the River Rats: they create a townwide campaign to “boycott immorality.” Fortunately Vianne has a different response to Roux and his gang, one not dissimilar to Christ’s response to the Samaritans, paralytics, lepers, prostitutes, tax collectors, and sinners. In the scene below Roux says to her, “I should probably warn you: You make friends with us, you make enemies with others.” Vianne responds, “Is that a promise?”

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yoGdST0RFuc&feature=relmfu&w=600]

The story of Chocolat unfolds over the course of the five weeks of Lent, presumably beginning on the Sunday just before Lent and ending on Easter Day. And it takes the full duration for Vianne to reach the Comte, and subsequently the entire town. The effect of Vianne’s graciousness can be seen in how the relationship between the Comte and the town’s young priest, Père Henri, changes. At the start of the film, we see that the Comte has a stranglehold on the message of Henri’s sermons. He insists on crushing themes of legalism and morality, which he especially wants to hammer home during Lent, editing the sermons to be an assault on temptations, Vianne, and the River Rats. However, the ultimate victim of the Comte’s legalism is himself. Plagued by the secret that his wife has left him, the hypocritical Comte cannot live up to the philosophy he espouses. The night before Easter, he breaks into Vianne’s chocolate shop to destroy her window display (which he considers sacrilegious), but he accidentally gets a taste of the chocolate. In a moment of weakness, he gorges himself to the point of passing out. Finally, the Comte recognizes his own need for mercy, and Henri’s message changes to one of grace. Thus, the townspeople finally hear some good news on a Sunday:

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BPtIJY5Tfq8&feature=related&w=600]

So what lesson do we take from Chocolat? Yes, Lent is a season of abstinence, etc. And the fasting and general austerity can be helpful in recognizing our need for mercy and redemption and repentance. But as Christ warns in the passage from Matthew 6, typically read in churches on Ash Wednesday: “Beware of practicing your piety before others in order to be seen by them.” Lent is not about practicing one’s piety, or the slippery slope of works righteousness and so-called boycotts of immorality. Rather, we remember the Good News that Dietrich Bonhoeffer so eloquently articulates in Life Together:

The Christian is the man who no longer seeks his salvation, his deliverance, his justification in himself, but in Jesus Christ alone. He knows that God’s Word in Jesus Christ pronounces him guilty, even when he does not feel his guilt, and God’s Word in Jesus Christ pronounces him not guilty and righteous, even when he does not feel righteous at all. The Christian no longer lives of himself, by his own claims and his own justification, but by God’s claims and God’s justification. He lives wholly by God’s Word pronounced upon him.

This is the Gospel: As a result of Christ’s work, not our own, we are announced righteous, even/especially though we are far from it. And this is exactly what happens in Chocolat. Vianne is the Christ figure not because she is crucified but because she pronounces everyone she meets as righteous despite their guilt. The beauty, of course, is that her announcement tends to have an improving or transformative effect for each of these people (some more gradually than others). We would be wise this Lent to remind ourselves of the Gospel, so that we might err on the side of Vianne rather than that of the Comte. But even if we are aggressively self-righteous like the Comte, praise be to God that grace will eventually bring us to our knees and lighten our spirits.

On that note, I leave you with this final clip:

COMMENTS

7 responses to “The Law and Gospel (of Lent) according to Chocolat”

Leave a Reply

Matt, I love your perspective on this film as much as I love the film. I wrote about it a couple years ago on my personal blog, talking about food as grace. Viewing it within the framework of the Lenten season makes the film’s themes of grace versus law even more prevalent. bravo! Also, in a shameless plug for myself, here’s the link to the post I wrote, if anyone is interested: http://losingsightofland.wordpress.com/2010/02/01/food-as-grace/

What an interesting & excellent article! Thank you!

Love that Bonhoeffer quote!

Thanks.

And for the record, I saw Chocolat. Just delightful.