This one was written by Nathan F. Elmore.

Se7en, David Fincher’s 1995 somber thriller, showcases my third-favorite villainous film character. It’s a dubious ranking, to be sure. Nonetheless, for me, in second place: Heath Ledger’s terroristic turn as the kind of Joker who is not kidding about burning it all down in Christopher Nolan’s Batman iteration, The Dark Knight. In first place—by a long, West Texas mile—the coin-flipping hitman Anton Chigurh, who darkens and chills scene after scene in the Coen Brothers’ No Country for Old Men.

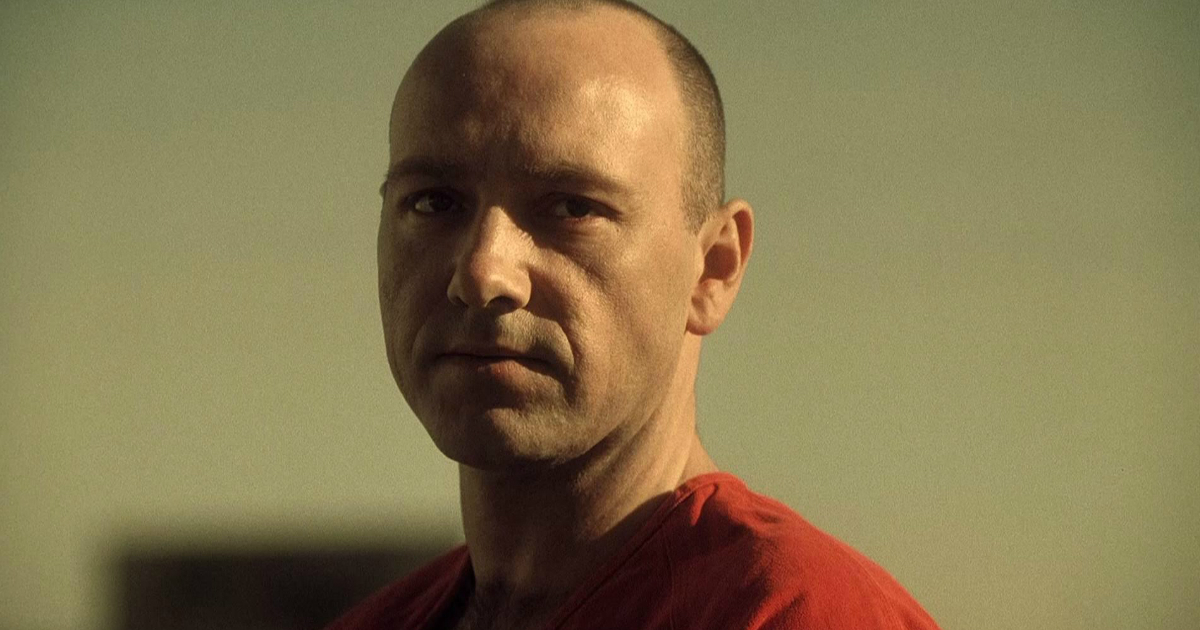

In Se7en, the capital vices are consuming a peculiar Adam named John Doe. As the story goes, he gruesomely but effectively spends his days creating performance-art installations (of a rather disturbing kind). Culturally, these installations function as vivid emblems of just how badly humanity has missed the mark, morally and socially.

John Doe’s artwork is as shocking as it is violently criminal. To represent Pride, for instance, he mutilates the face of a model, giving her the option of living a disfigured life or committing suicide with pills. Not to be outdone, he force-feeds an obese man until his stomach ruptures (Gluttony). His canvas for illuminating Sloth involves strapping a drug dealer to a bed and keeping him alive but just barely—a fitting ode to a life defined by lazy choices.

Each of these handmade installations turns the sin against the sinner. A sociopath with panache, John Doe’s mannerisms and methodologies reveal a person of religiously-styled devotion—not unlike extremists of assorted religious varieties. The walls in his apartment are painted jet-black, suggesting a season of societal mourning. Iconography is scattered about different rooms, including a red, neon cross that hangs in his bedroom; it emits, we suppose, a light to see by. Even his bare-bones cot conjures a monk’s ascetic lifestyle. Meanwhile, taken from his own grisly crime scenes, John Doe keeps relics fit for a spiritual pilgrimage: tomato-sauce cans from the gluttony murder; blood-stained law books from the greed killing; the severed hand of his sloth victim.

Alongside the detectives, we happen upon his journals. Unsurprisingly, they ooze of angst-y meditations and vitriolic diatribes. In the deep recesses of his mind it is evidently crystal clear: he is offering you and me a grace, a gift, as shocking as that sounds. It’s as if, with his own (bloody) hands, he is holding out a gift for us—that is, for anyone with eyes to see and ears to hear. Shortly after turning himself in, he tells the detectives: “Wanting people to listen, you can’t just tap them on the shoulder anymore. You have to hit them with a sledgehammer, and then you’ll notice you’ve got their strict attention.”

And indeed he has gotten our strict attention. As the film moves toward its climactic moment, he bemoans the lack of any real social contrition on your part and mine. He undresses the stark nakedness of a willful ignorance that can only be described as, well, human. From the back seat of a police cruiser, he can’t help but offer the detectives his guiding theology of shock value: “Only in a world this shitty could you even try to say these were innocent people and keep a straight face.”

Both in word and deed, the argument of John Doe is that there is a direct line between our moral complacency and our fatal flaw. It keeps us from what we so desperately need, and dulled senses need some measure of disturbance. In the film Gladiator you might recall the masses having become wretchedly under the spell of blood-sport. We witness an emboldened Maximus unsettling the status quo with that ironic yelp: “Are you not entertained?” Se7en’s version would likely be: “Are we not disturbed?”

Or are we?

In the enduring, global narrative of God, gospel-people believe that the resurrection of Jesus—what theologian Walter Brueggeman calls “an intervention of newness”—has disturbed and is disturbing all that is dead or dying. God has dramatically intervened in the midst of our overwhelming sin and surrounding darkness. Perhaps here is the most-meta meaning of that culturally in vogue phrase “to get woke”: to experience the fullest effects of resurrection disturbance.

Of course, God has employed various forms of shock value, especially toward human wakefulness, for quite a long time. Take that illustrious ancient tale described in the biblical book of Jonah. We see Nineveh—“that great city,” a magnificently evil city—awaiting her intervention for the good. She doesn’t know it yet, but the God of Israel is intent on bringing all of humanity back to life from the brink of our many deaths.

I’m convinced Jonah ran because he absolutely knew that God always had it in him: this grace which goes by the name mercy. Here was a gift that could save the worst of us from his judgment and—perhaps Jonah’s deeper heart-struggle—here was a gift that, shockingly, included even Ninevites in the new family and in the beloved community. Sure, there was fear and trepidation within Jonah. But it was what the prophet did not have in him that perhaps is the longer-lasting moral of the story.

As you may remember, God has him thrown into the deep sea, swallowed by a big fish, and, after a kind of baptism, vomited up onto the shore. There is an initial change in the prophet, whose heart bends in the direction of God’s story. Nineveh and her inhabitants are restored and transformed. Then, like in Se7en, comes that small matter of the story’s ending.

We become privy to a tired, sulking, disturbed messenger, his arms (imaginatively) folded tightly. His is the glare of a passionate nationalist with a narrow worldview who is suffering the usual disappointments with a god made in his image. On the other hand, there is God—he is standing in an otherwise shitty world, to quote John Doe, his arms (imaginatively) open wider than any sea with a thousand whales. And if we’re being utterly honest, it’s still shocking, this gift.

COMMENTS

3 responses to “Shock Value”

Leave a Reply

How pedantic should I be? At least this much – the movie wasn’t called “Se7en” but “Seven” in its theatrical release (and, I think, in the first wave of video releases). They retconned the name. Rather lamely.

Good piece though.

Adam, that’s on me as the proofer. I just thought “Se7en” looked cooler. 🙂

My problem is that I remember the theatrical release, and then seeing it in video stores (dear God I’m old) with “Seven” on the box.

When they changed it a while later, I couldn’t help (still can’t) but pronounce as Sesevenen.