This election cycle, Donald Trump’s ascendancy to front-runner status has given religion beat writers a whole new angle of thinkpiece to write: what exactly is an Evangelical, and why are they voting for Trump. At least a half-dozen of them are produced daily, it seems, from major publications like The Washington Post and the New York Times to your friendly neighborhood religious blog. Evangelical bastions like Christianity Today magazine and Liberty University are weighing in on the discussion, and even smaller Evangelical outlets like Relevant Magazine are trying to parse the Trump phenomenon. Flummoxed political insiders aren’t the only ones left scratching their heads these days.

This election cycle, Donald Trump’s ascendancy to front-runner status has given religion beat writers a whole new angle of thinkpiece to write: what exactly is an Evangelical, and why are they voting for Trump. At least a half-dozen of them are produced daily, it seems, from major publications like The Washington Post and the New York Times to your friendly neighborhood religious blog. Evangelical bastions like Christianity Today magazine and Liberty University are weighing in on the discussion, and even smaller Evangelical outlets like Relevant Magazine are trying to parse the Trump phenomenon. Flummoxed political insiders aren’t the only ones left scratching their heads these days.

These thinkpiece articles are certainly onto something as they wrestle with the category of Evangelical and the disconnects of their Trump support. The guy with multiple divorces leading the party of family values? The owner of casinos with strip clubs followed by the people who invented purity rings? The guy who’s never asked forgiveness heading a parade of the divinely forgiven? You don’t need a quiet room in a library to write that article.

Let’s funnel down a bit to one particular type of thinkpiece- perhaps the most popular of the Trump/Evangelical essays. Boiled down, you might call them the “they’re not Evangelicals” articles. This response to the religious success of Trump suggests that Trump voters “aren’t really Evangelicals” in the truest sense.

Take the Wapo op-ed from The Southern Baptist Ethics & Liberty Commission’s Russell Moore:

Many of those who tell pollsters they are “evangelical” may well be drunk right now, and haven’t been into a church since someone invited them to Vacation Bible School sometime back when Seinfeld was in first-run episodes…

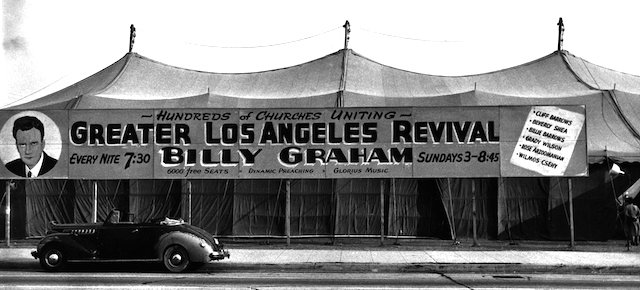

Evangelical is a magnificent word — a word that resonates with the gospel dissent of Martin Luther and the gospel crusades of Billy Graham. More than that, it is rooted in the New Testament itself that tells us that Jesus saves. And I’m not ready to give it up yet.

But you will forgive me if, at least until this crazy campaign year is over, I choose just to say that I’m a gospel Christian.

When this fevered moment is over, we will need to make “evangelical” great again.

Or, in this NYT piece from Trip Gabriel, which concludes with quotes from the perfect example of the “questionable Evangelical” voter:

Paul Smith, a machinist in Oklahoma City, called himself a “total Christian” but said he did not attend a church because “I’ve witnessed too much hypocrisy” in churches. “I’ve been with Donald Trump since he put his hat in the race,” he said. “Basically he’s anti-establishment.”

One more before moving on- from Dr. Richard Land, President of Southern Evangelical Seminary, over at The Christian Post:

[Dr.] Land questioned the bona fides of the Trump supporters who self-identify as evangelicals in exit polling and charged that true evangelicals vote their values. He also noted that the Bible did not call Christians to be pragmatic when it comes to their faith.

“I vote my values, my beliefs and my convictions, I’m not pragmatic. Which means I don’t compromise my values, beliefs and convictions for what I may perceive to be my own narrow self-interests

There’s a real question of category here that does need to be addressed: the term Evangelical no longer means what it meant in previous election cycles (if it meant anything at all). We can agree that self-identity isn’t necessarily the best way to measure this category, as evidenced by the somewhat anecdotal finding that church attendance is a marker of Trump opposition, not Trump support.

At the same time, as these essays continue to be published, it’s hard not to to see the “No True Scotsman” logical fallacy at play. Besides having a flashy and fun name (see also: Red Herring), the No True Scotsman fallacy is an attempt to deflect accusations about a community by shrinking the community. The term was coined by this thought exercise (courtesy of Wikipedia!) from British Philosopher Antony Flew:

Imagine Hamish McDonald, a Scotsman, sitting down with his Glasgow Morning Herald and seeing an article about how the “Brighton (England) Sex Maniac Strikes Again”. Hamish is shocked and declares that “No Scotsman would do such a thing”. The next day he sits down to read his Glasgow Morning Herald again; and, this time, finds an article about an Aberdeen (Scotland) man whose brutal actions make the Brighton sex maniac seem almost gentlemanly. This fact shows that Hamish was wrong in his opinion, but is he going to admit this? Not likely. This time he says: “No true Scotsman would do such a thing”.

Simplified to our situation, it’s easy to suggest that “no Evangelical would vote for Trump” and then, when presented with evidence to the contrary, double down and suggest “no true Evangelical would vote for Trump.”

Let’s set aside for now that there is no agreed upon definition of an evangelical: it’s still hard not to suspect that this conversation has as much to do with posturing as it does demographics. It’s what Allen Guelzo in last November’s Christianity Today thoughtfully titled “the Idol of Respectability.” In that instance, Guelzo was referring to the temptation of the academic Christian to forfeit faithfulness for secular professional advancement. We might also expand that idol to include civic minded Christians disavowing Evangelicals for the sake of respectability in the “public square.” While it’s true that polling data should be adjusted to reflect changing demographics of the value voters, it’s worth examining whether these attempts to shed or modify the Evangelical moniker are about personal identity and respect. It’s a way of flagging to the world: “I don’t believe like they believe. Don’t loop me in with them.”

St. Paul wrestles with these categories of identity throughout the New Testament, having to reassert his Scottishness– er, Jewishness– to counter the community shrinking attempts of Judiazers, who suggested “no true Christian would teach you to remain uncircumcised.” In Philippians 3, Paul shares a full and complete resume as to why he has religious authority: circumcised on the eighth day, of the people of Israel, of the tribe of Benjamin, a Hebrew of Hebrews; as to the law, a Pharisee, etc. As he concludes sharing his resume, he tears it up, literally calling his resume and attempts at identity justification BS. He dubs these Judiazers “dogs” for trying to draw a line in the sand between “real Christians” who do extra on top of believing the gospel and “lesser Christians” who should be kept at a distance. As the Pharisee once said in prayer, “thank God I’m not like those people.” (Luke 18)

Definitions are helpful, but the moment they’re used as distinctions between who’s in and who’s out, we tread on shaky ground. The authors of the U.S. Constitution thought it wise to prohibit religious tests as a prerequisite for politics. It’s equally wise for Evangelicals not to impose political tests for religious membership.

Perhaps its better to apologize in the public square for the vote of fellow Evangelicals, or acknowledge the failure of rigidly moralist discipleship to produce civic fruit. Apology and confession both do better by the Gospel than self-justifying the Evangelical moniker and kicking others out. After all, come November, who knows what lines in the sand we’ll quietly erase behind the privacy of the ballot box curtain.

Which is not to say it’s any better to draw lines between us and the line drawers. By way of confession, the impetus for this line of thought centered around the fact that I don’t know a single Trump supporter, even though I live in a hotbed of anti-Obama, let-DC-burn Appalachia. If the statistics are right, I’ve been drawing my own lines for some time, and, as we are often reminded, when we draw lines, it’s likely we’ll find Jesus on the other side.

COMMENTS

4 responses to “The Primary Definition of an Evangelical”

Leave a Reply

Or perhaps what we actually see here is what is ultimately at the bottom of American evangelicalism – which whilst it may have antecedants in past movements – exists in the present time as a fairly opportunistic political movement that is all about identity.

The silly thing is that those who claim that supporters of Trump are not “evangelical” would, more likely than not, point to an airhead like Ted Cruz as the “Christian alternative”.