I think people in their 20s and 30s pass through three stages with regard to the music they loved as adolescents: (1) “cringe,” to use contemporary parlance, (2) “ironic” enjoyment, and finally (3) genuine appreciation for what was (and is) truly valuable about it. I think I’ve reached the third stage with Christian rock outfit Switchfoot’s fifth studio album, Nothing is Sound (2005), released my sophomore year in high school. At the time, I thought the album to be cutting edge, prophetic even. It had a great deal more to say about the state of contemporary culture than anything they were playing on the local Christian stations! Or such was my sophomoric critical evaluation. Nothing is Sound is, perhaps unsurprisingly, full of overwrought angst and a little too on-the-nose social commentary (Sex is commercialized! Politicians are corrupt!).

But even in 2022, there are still a couple of tracks from the album that I revisit from time to time. One of these is “The Shadow Proves the Sunshine,” a prayer of hope which was lovely then and is lovely now. The other is “The Blues,” a piano-driven ballad that, being a meditation on the end of the world, is not exactly light on overwrought angst. Switchfoot’s frontman, Jon Foreman, penned the song on New Years Day 2004, lamenting that the kingdom has yet to arrive. “Is there any net left / That can break our fall?” Foreman asks during the bridge, before launching into one of those few lyrics that has burned itself, indelibly, into my memory: “It’ll be a day like this one / When the sky falls down / And the hungry and poor and deserted are found.”

Amen. Even now I can catch a glimpse of what Foreman saw: that the cycles of violence and structures of oppression that appear immutable are, in fact, like the chaff that wind drives away. That, suddenly, the last have become first, the meek have inherited the earth, the tanks have been turned into tractors, and justice and peace have finally kissed. The “real world,” the self-interest and cynicism and violence, has receded like a vanishing nightmare.

Foreman’s sense of the world’s ephemerality is deeply biblical, and Pauline in particular. The passing away of the “present evil age,” and its replacement through Christ by the “ages to come,” is a core theme of the apostle Paul’s theology. In his first letter to the Corinthian church, Paul advises believers against marriage on the grounds that they should limit their attachments to the current order of things:

This is what I mean, brothers: the appointed time has grown very short. From now on, let those who have wives live as though they had none, and those who mourn as though they were not mourning, and those who rejoice as though they were not rejoicing, and those who buy as though they had no goods, and those who deal with the world as though they had no dealings with it. For the present form of this world is passing away. (1 Cor 7:29-31)

For Paul, it is perfectly acceptable and even necessary for Christians to be about the ordinary business of human life right up until the End. This is hardly a call for apocalyptic separatism. It is a call for believers to be careful where they put their hope for a good future. If that hope is built on anything in this world turning out a particular way, then that hope will surely disappoint. Indeed, “nothing lasts in this life” (Switchfoot). For that reason, “we look not to the things that are seen but to the things that are unseen. For the things that are seen are transient, but the things that are unseen are eternal” (2 Cor 4:18).

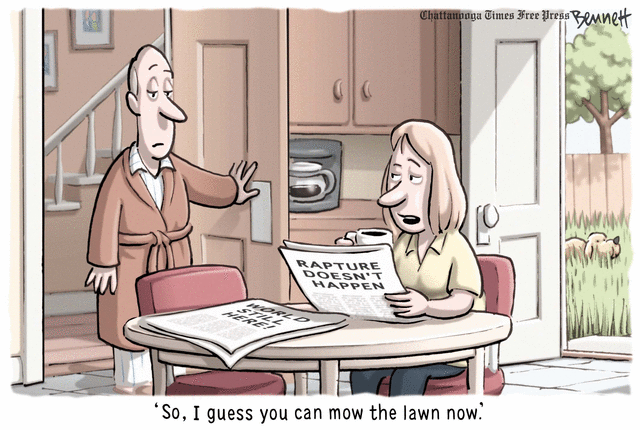

Christianity has drawn a lot of flack over the years for this eschatological emphasis. The critics point out that it’s facile, maybe even perverse, to hope and pray for the “ages to come” instead of devoting that energy towards making this present age a little less evil and a little more livable. And there’s no doubt that eschatology can be mere escapism. I distinctly remember people loudly asking Jesus to come back in the throes of the 2000 presidential election so that we might avoid the prospect of a Gore presidency.

On the other hand: we are not really making a lot of progress towards building Jerusalem “in Englands green & pleasant Land,” or anywhere else for that matter. There’s no need for me to provide the laundry list of the disasters that have unfolded over the last two weeks. Granted, the state of the world is not the worst that it’s ever been, by any stretch of the imagination. Even so, hope feels really hard to come by right now. The good news is that we don’t have to look at the empirical evidence for reasons to hope, or to gin up some kind of bravado to face the darkness. In receiving the gift of faith in Jesus Christ from God, Christians also receive the gift of hope for a world made new in Christ.

On the other hand: we are not really making a lot of progress towards building Jerusalem “in Englands green & pleasant Land,” or anywhere else for that matter. There’s no need for me to provide the laundry list of the disasters that have unfolded over the last two weeks. Granted, the state of the world is not the worst that it’s ever been, by any stretch of the imagination. Even so, hope feels really hard to come by right now. The good news is that we don’t have to look at the empirical evidence for reasons to hope, or to gin up some kind of bravado to face the darkness. In receiving the gift of faith in Jesus Christ from God, Christians also receive the gift of hope for a world made new in Christ.

Such hope is essential in facing down “the present form of the world” and in making some progress towards improving it for our neighbors and children. Hope is a key part of our inheritance in Christ, so let’s receive from his hand and cling to it for dear life.

COMMENTS

Leave a Reply