This one comes to us from Jason Micheli.

You would never guess it from the way they greet one another along the sidewalk in the morning or wave as they jog their dogs after work, but just about everyone in my neighborhood believes America’s partisan cold war is about to ignite with fire and fury. Depending on who you ask, we are sitting on either the brink of civil war or the end of the democracy itself. They’re all angry and afraid, convinced that we have arrived at an apocalyptic inflection point in our history. Of course, you’d never know they hold these convictions with religious zeal by driving through our neighborhood. Biden and Trump campaign signs are sparse. This summer I heard none of my neighbors voice their fears or antagonize one another on the deck of our community pool. But, they do tweet them. And they share posts on Facebook with the vitriol of a WWE heel — except no one is pretending.

This may be an odd time in history, but it’s not unique.

It’s often forgotten the extent to which political propaganda and siloed partisan media outlets in Germany created the conditions that made possible the Kaiser’s war effort, the resentment and conspiracy-mongering that followed its defeat, and the rise of German nationalism. Like us, Germans were hyper-political and had politicized every aspect of their lives. Political tribalism extended into other areas of German life such that one’s party affiliation extended into every other components of social life. As Richard Evans notes in The Coming of the Third Reich, “Choirs, sports clubs, libraries, youth groups, women’s organizations, dramatic societies — even pubs — identified themselves in political terms: as Social Democrat, nationalist, Centre, and so forth.” German politics was a lifestyle brand, or what David Zahl would call seculosity.

This was the climate in which the Protestant theologian Karl Barth began holding his “Exercises in Sermon Preparation” in 1932 at the University of Bonn. Barth was from Switzerland and had signed an oath to refrain from political organizing as a condition of employment in Germany, but Barth felt called to give these future communicators an alternative to the toxic and partisan rhetoric that had infected every aspect of German life.

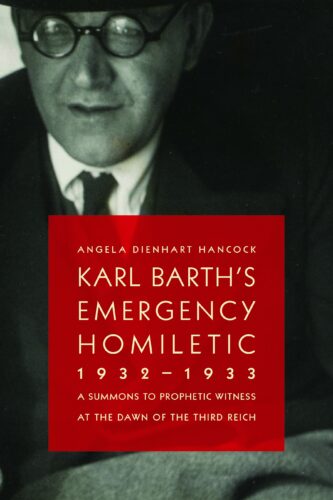

In shaping these lectures on preaching, Karl Barth returned to his thoughts in the second edition of his commentary on Paul’s Letter to the Romans. In his exegesis of Romans 12 and 13, the question of the ethics of revolution came to the fore as Barth reflected upon the relationship between the Church and the State. To would-be activists and revolutionaries, especially Christians (rightly) dissatisfied with the status quo, Barth’s counsel bears resisting for our own fractured, Flight-93 time. Barth believed Paul’s epistle provides no justification either for reactionary, nationalistic conservatism or violent left-wing revolution. According to his reading of Romans, as Angela Hancock notes in her book Karl Barth’s Emergency Homiletic, Karl Barth argued that Christians should resist the absolute claims of the State, ideological leaders, and political parties by depriving them of their pathos. Barth writes:

In shaping these lectures on preaching, Karl Barth returned to his thoughts in the second edition of his commentary on Paul’s Letter to the Romans. In his exegesis of Romans 12 and 13, the question of the ethics of revolution came to the fore as Barth reflected upon the relationship between the Church and the State. To would-be activists and revolutionaries, especially Christians (rightly) dissatisfied with the status quo, Barth’s counsel bears resisting for our own fractured, Flight-93 time. Barth believed Paul’s epistle provides no justification either for reactionary, nationalistic conservatism or violent left-wing revolution. According to his reading of Romans, as Angela Hancock notes in her book Karl Barth’s Emergency Homiletic, Karl Barth argued that Christians should resist the absolute claims of the State, ideological leaders, and political parties by depriving them of their pathos. Barth writes:

It is evident that there can be no more devastating undermining of the existing order than the recognition of it which is here recommended, a recognition rid of all illusion and devoid of all the joy of triumph. State, Church, Society, Positive Right, Family, Organized Research, and so forth live off of the credulity of those who have been nurtured upon vigorous sermons-delivered-on-the-field-of-battle and other suchlike solemn humbug. Deprive them of their PATHOS, and they will be starved out; but stir up revolution against them, and their PATHOS is provided fresh fodder. (Romans)

By “pathos” Barth points back to his treatment of the word in Romans 7:5 where Paul uses the word to speak of “the sinful passions” to which we are all prone to fall captive. The lesson is that we should not give to our party politics the passion they seek; that is, we should not invest them with eternal importance. Once given the ultimate pathos it seeks, political ideology has the power to extract from us all sorts of self-justifications that lead us in directions contrary to the good. That this is a word of caution needed by leftist and Trumpist activists alike seems self-evident. Rather than imbue politics with religious zeal, Barth writes that those who seek the common good should “do their best to prevent the intrusion of religion into that world. They will lift up their voices to warn those careless ones, who, for aesthetic or historical or political or romantic reasons, dig through the dam and open up a channel through which the flood of religion may burst into the cottages and palaces of men.”

Barth’s recommendation extends beyond ideology and politics to those who participate in them. Deprive them of their pathos; don’t give them the endorphin rush of their righteous indignation. Don’t buy into activists’ insistence that ______ issue means we must, as Barth put it, “storm the heavens.” With good cheer — the love of neighbor — refuse to grant the premise of their rhetoric; that is, refuse to accept that this or another political issue is an end of such ultimate, consequential stakes that any means of success are thereby justified. Political activity is important and necessary, but should be engaged as “a game that is played in full and vigilant awareness of its relativity” (Barth’s Emergency Homiletic).

In other words, to deprive them of their pathos is in fact an exhortation to extend grace, ignoring a perceived transgression and reckoning in its place a goodness that may not be present.

In other words, to deprive them of their pathos is in fact an exhortation to extend grace, ignoring a perceived transgression and reckoning in its place a goodness that may not be present.

In 2016 and now in 2020, activists on both ends of the political spectrum have compared the voting booth to “a Flight 93 moment,” hearkening back to the brave, selfless passengers who did whatever was necessary on 9/11 to down the hijacked plane before it could wreak unimaginable devastation. To novice communicators of the gospel, in the thick of nationalistic propaganda and fascist demagoguery, Barth cautioned against exactly this sort of rhetoric that presently chokes our national discourse. It does not deprive the left of their pathos, Barth would likely say, but only ensnares them into responding in kind; likewise, seeing the defeat of President Trump at the polls this November as an existential crisis and an apocalyptic threat to America does nothing to starve his MAGA-clad fans of their sense of belonging to something ultimate. It deprives no one of their pathos to call those in one party deplorable nor to identify your own side as “the coalition of the decent.”

Barth’s thinking in Romans is a word we all need to hear. If Barth could write this in the time of Hitler (he eventually lost his post and was exiled to Switzerland), then our own circumstances do not exempt us from his wisdom. Barth was hardly a disengaged quietist, yet he worried that the measured reflection and back-and-forth negotiation required by democratic politics had been replaced by “the convulsions of revolution.” Any healthy politics must be grace in practice, for it requires a humility which is only made possible by the recognition that all participants involved are not only finite but inescapably sinful creatures. Or, as Barth puts it, politics is only sustainable when “it is seen to be essentially a game; that is to say, when we are unable to speak of absolute political right.”

To deprive them of their pathos is to reserve for God what is God’s alone, the adjudication of absolutes.

Pathos — investing politics with all-encompassing meaning and identity — results, as Angela Hancock notes, “in an escalating exchange of the political propaganda. Because their respective political views are held with deadly eternal seriousness, neither critical distance nor reasoned dialogue about politics is possible any longer.”

The neighbor who picks up my newspaper for me from the driveway is the same person who, according to Facebook, thinks people like me (i.e., people who think maybe we should talk about racism) “hate America and think only armed resistance will solve the problem.” Sarah Condon says we know now as much about social media as smokers did in the ’20s about cigarettes. One day, gasping for our last breath, I wager we’ll discover that one of the tolls taken by social media, shepherding us into ever more precisely partisan echo chambers, is that it did not allow us to do the one thing Karl Barth learned we must do when it comes to politics.

The most extended biblical meditation on the Lord’s Supper occurs in the context of Paul’s letter to the Corinthians, in which the Apostle rebukes his flock because they do not “discern the body” during the Lord’s Supper (I Corinthians 11:29). The context makes clear that by “discern the body” Paul does not mean the bread or wine themselves; he means the diversity of members that make up the Church body. Paul’s admonition to discern the body was, in Corinth, a rebuke of the way in which the Church had segregated rich from poor, male from female, spiritual from irreligious, Jew from Greek. The New Testament instructs us to celebrate the Lord’s Supper in such a way that we are forced to reckon with the nature of the motley crew Jesus draws together. To celebrate with bread and wine in a way that allows you to avoid those whom you would never choose as friends — except that Jesus has first befriended you — is to celebrate something other than the Lord’s Supper of the New Testament.

In that same meditation, Paul warns that “those who eat and drink without discerning the body of Christ eat and drink judgment on themselves.” If there is an ecumenical corollary from sacrament to public square, then perhaps we’re all now sick from the judgment we’ve feasted upon in our politics for too many years. And if there’s a remedy to what ails us politically, then perhaps it’s in line with St. Paul’s own prescription, to get out of our social media silos and into places where we must discern the body politic and engage it in all its diversity. Only in the latter spaces will we discover the power to deprive them, with good cheer, of their pathos.

Image credits: IDuke, Bundesarchiv, Bild 194-1283-23A / Lachmann, Hans / CC-BY-SA 3.0

COMMENTS

One response to “Deprive Them of Their Pathos: Partisan Politics, Social Media, and Karl Barth”

Leave a Reply

shades of Eric Voegelin!