If you’re not aware of James Parker’s mini-column “An Ode to …”, found in every issue of The Atlantic, you might want to add it to your list of regular delights. Each 500-word piece — An Ode to Small Talk, An Ode to Fallibility, An Ode to Cold Showers — is a playful, astute look into the more banal parts of life. Parker has written a number of pieces that we’ve highlighted over the years, but these tiny, intimate portraits are an art form in and of themselves, each taking between 60-90 seconds to read, depending on your reading level.

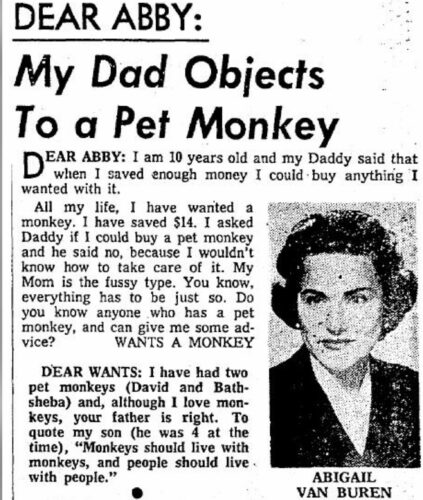

His latest, “Ode to Agony Aunts,” is a look into advice columns (“Ask Polly,” “Dear Prudence,” etc). When Parker was a boy he would read them from his mother’s magazines, feeling more than a bit voyeuristic. He was enamored with people’s personal problems splayed out for all to see. It felt like a private seat in a confessional booth. Parker recites a laundry list of human problems, simultaneously specific and universal.

The problems are the same, now and forever. The same dilemmas, the same misunderstandings. Is my boss a pig? Why won’t my stepdaughter say thank you? I married a frog — I thought he was a prince! They loop around, they rhythmically recur, albeit touched with the flavor of the times (“Help, My Pandemic Crush Feels So Real!”). And the problem of all problems, the old chestnut: Why am I doing what I’m doing, when it’s so obviously bad for me? Saint Paul put this one best in his letter to the Romans: “For what I would, that do I not; but what I hate, that do I.”

As we are in the middle of what many consider a “make or break” moment in our nation’s history, it is a humbling reminder that not everything is riding on who is president. No matter who is sitting at the Resolute Desk, you’re still going to have petty arguments about how to load the dishwasher and midnight crises about your life stalling out. Aren’t those problems worth addressing, too? Parker notes that while our personal problems might be strangely particular, their tendency to complicate our lives isn’t:

How tangled we get. How impossible it is, apparently, to be alive without sitting on somebody, or being sat on. Is it freedom you want? The swingers have their problems too (“I Love My Poly Lifestyle, but the Constant Sex Has One Big Drawback”).

Parker is hitting on the universal need for resolution. A problem, by definition, is something that you cannot solve. Otherwise, it wouldn’t be a problem. And Parker spends little time before getting to the bottom of all the problems of the world: the human heart in conflict with itself. The fact that he exemplifies Romans 7 in a magazine like the Atlantic surely speaks to the universal experience of the bound will, not to mention the power of sin.

Parker then pivots to the authoritative respondent, Ms. Ask Polly herself. An answer is given. A solution is presented. Where there was tension, there is release. Where there was confusion, there is certainty. He closes with his own obsession with the world of questions and answers:

Voyeurism and schadenfreude — we know our own baseness, we who lurk in the problem pages. But we’re also holding out, childlike, for something beautiful: the idea of a consummately wise person who can take us in hand. Who has all the answers. Who will know what to do when the weight of our situation exceeds the load-bearing capacity of our psychological frame. Because it’s much to be anticipated, much to be wished for — the day when our problems are over.

Isn’t that what everybody wants? Truth be told, there is nothing like a problem getting solved. Aspirin healing a headache. A patched tire getting you on the road again. As Mary Karr’s poem “The Voice of God” famously observes, “Ninety percent of what’s wrong with you could be cured with a hot bath.” Our God is, indeed, mighty to save, albeit often in unexpected ways.

As for real, clear solutions, part of the quandary of Christian ethics is its genuine lack of specifics. The New Testament is not an advice column in any way, shape, or form. Paul speaks broadly of the fruit of the Spirit or renewing your mind or conforming to Christ, but he doesn’t exactly outline the day-to-day of life. He doesn’t answer questions about how to raise children or how to conduct a business ethically. The reason for this could be explained as a function of freedom that comes from and with the Holy Spirit, that “wise person who can take us in hand.” In other words, what we want from an advice columnist seems to be precisely what Paul thinks the Spirit is for: taking our mundane questions about life, pointing us to Jesus, and returning an answer that conforms to his image.

In light of the gospel, the Holy Spirit’s advice column is very much in tune to the Beatles’ response to our daily conundrums: “Dear Prudence, won’t you come out to play?” I am banking on that childlike quality of Parker’s hope being grounded in something eternal. Jesus, after all, is the person who takes us in hand, who is the very Truth we seek, who took the weight of our situation that far exceeded the load-bearing capacity of our psychological frame. He is the answer to our eternal problem.

In the meantime, of course, advice-columnists will never be out of work. We who seek resolutions to life’s internal problems will keep seeking. Sometimes there will be nothing left to do but throw up one’s arms and say, “Oh, well.” But I’d be surprised if the solution to a personal problem didn’t have something to do with the grace of God just about every time.

Featured Image from The Atlantic

COMMENTS

Leave a Reply