Hopefully you saw Andy Crouch’s thoughtful piece in the Wall Street Journal this past weekend, “Steve Jobs, The Secular Prophet”, which explores the religious parallels that have become increasingly blatant (everywhere you look) in the days following Jobs’ death. I mentioned some bewilderment at the widespread emotional outpouring in Friday’s Another Week Ends column, and Crouch’s article touches on a number of the reasons why. Clearly a major spiritual vein has been exposed, one that goes beyond mere cultural preoccupation. Crouch does a fine job of unpacking the dynamics at work, particularly as it relates to the ‘message’ or hope that Jobs made no bones about preaching. Or at least including as a, um, core part of Apple’s marketing strategy, sincere as it may have been.

Hopefully you saw Andy Crouch’s thoughtful piece in the Wall Street Journal this past weekend, “Steve Jobs, The Secular Prophet”, which explores the religious parallels that have become increasingly blatant (everywhere you look) in the days following Jobs’ death. I mentioned some bewilderment at the widespread emotional outpouring in Friday’s Another Week Ends column, and Crouch’s article touches on a number of the reasons why. Clearly a major spiritual vein has been exposed, one that goes beyond mere cultural preoccupation. Crouch does a fine job of unpacking the dynamics at work, particularly as it relates to the ‘message’ or hope that Jobs made no bones about preaching. Or at least including as a, um, core part of Apple’s marketing strategy, sincere as it may have been.

Clearly, many Apple users – particularly young ones – identified with Jobs’ Gospel of Progress. For them, his SteveNote talks were a combination state of the union address, worship service and magic show. And there was something undeniably exciting about those presentations i.e. what would he say next?! As a Christian, I happen to think Jobs was on to something about death being life’s change agent (big time), but still, the notion that technological advances could/would/should have any bearing on the profoundly static human condition – that technology has the power to make the world a better place, fundamentally – seems painfully lacking, as Crouch makes clear in his conclusion. That folks of my/any generation would be so taken in by it, so attached to it as an ethos that Jobs’ death would provoke straight-up veneration, strikes me as more than sad; it’s strikes me as, well, a little pathetic. Is this really what passes for wisdom these days? Would Jobs have even meant it to? Or am I ascribing an ideological ‘buy-in’ that’s not there? Are people simply mourning the fact that their next tech upgrades might not be as cool as they would have been if Jobs had lived?

Personally speaking, as much as I love my Apple products (and have since my first powerbook in 1998 – zing!), if I’m being honest, they have not been agents of peace or happiness or even relief in my life. Not by a long shot. And I suspect I’m not alone. If anything, my deeply entrenched iLife is emblematic of the illusion at the heart of all ‘idolatry’: that the next email will scratch the affirmation itch more satisfactorily, the next blog post, the next text, etc. Machines that promise control but deliver the opposite, re-contextualizing our inner agitation and bondage more successfully with each passing year/model, rather than assuaging it (remotely). Not that the tech itself is to blame in any way – someone’s got to make the most user-friendly, attractive, high-performing products and I for one am grateful I don’t have to cart all my CDs around any longer – just that any deeper ‘promise’ is so clearly belied by experience …he types… on his Macbook Pro… while listening to iTunes:

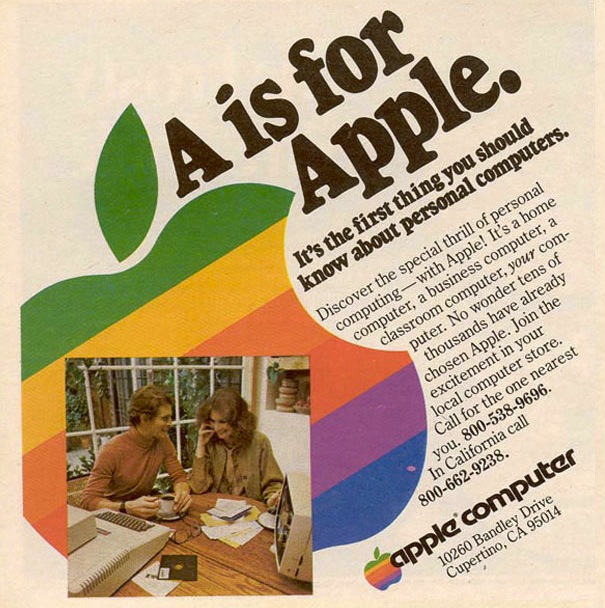

Steve Jobs was extraordinary in countless ways—as a designer, an innovator, a (demanding and occasionally ruthless) leader. But his most singular quality was his ability to articulate a perfectly secular form of hope. Nothing exemplifies that ability more than Apple’s early logo, which slapped a rainbow on the very archetype of human fallenness and failure—the bitten fruit—and turned it into a sign of promise and progress.

That bitten apple was just one of Steve Jobs’s many touches of genius, capturing the promise of technology in a single glance. The philosopher Albert Borgmann has observed that technology promises to relieve us of the burden of being merely human, of being finite creatures in a harsh and unyielding world. The biblical story of the Fall pronounced a curse upon human work—”cursed is the ground for thy sake; in sorrow shalt thou eat of it all the days of thy life.” All technology implicitly promises to reverse the curse, easing the burden of creaturely existence. And technology is most celebrated when it is most invisible—when the machinery is completely hidden, combining godlike effortlessness with blissful ignorance about the mechanisms that deliver our disburdened lives.

Steve Jobs was the evangelist of this particular kind of progress—and he was the perfect evangelist because he had no competing source of hope. He believed so sincerely in the “magical, revolutionary” promise of Apple precisely because he believed in no higher power.

This is the gospel of a secular age. It has the great virtue of being based only on what we can all perceive—it requires neither revelation nor dogma. And it promises nothing it cannot deliver—since all that is promised is the opportunity to live your own unique life, a hope that is manifestly realizable since it is offered by one who has so spectacularly succeeded by following his own “inner voice, heart and intuition.”

Mr. Jobs was by no means the first person to articulate this vision of a meaningful life—Socrates, the Buddha and Emerson come to mind. To be sure, fully embracing this secular gospel requires an austerity of spirit that few have been able to muster, even if it sounds quite fine on the lawn of Stanford University.

Upon close inspection, this gospel offers no hope that you cannot generate yourself and only the comfort of having been true to yourself. In the face of tragedy and evil—the kind of tragedy that cuts off lives not just at 56 years old but at 5 or 6, the kind of evil bent on eradicating whole tribes and nations from the earth—it is strangely inert.

…the genius of Steve Jobs was to persuade us, at least for a little while, that cold comfort is enough. The world—at least the part of the world in our laptop bags and our pockets, the devices that display our unique lives to others and reflect them to ourselves—will get better. This is the sense in which the tired old cliché of “the Apple faithful” and the “cult of the Mac” is true. It is a religion of hope in a hopeless world, hope that your ordinary and mortal life can be elegant and meaningful, even if it will soon be dated, dusty and discarded like a 2001 iPod.

For people of a secular age, Steve Jobs’s gospel may seem like all the good news we need. But people of another age would have considered it a set of beautifully polished empty promises, notwithstanding all its magical results. Indeed, they would have been suspicious of it precisely because of its magical results.

…technological progress, for all its gifts, is the exception rather than the rule. It works wonders within its own walled garden, but it falters when confronted with the worst of the world and the worst in ourselves.

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X2v4OH39UgM&w=600]

COMMENTS

10 responses to “Steve Jobs Is My Co-Pilot?”

Leave a Reply

I agree. Jobs’ death has revealed an element of quintessential “idol-worship”. Two major players in the response are: the love of autonomous professional success, and the love of materialism (and the intersection of the two).

note: that comment was typed on my beloved MacBook. 😉

For once, DZ, I strongly disagree with you. Whatever he was like as a manager — equal parts terrifying and inspiring, from all accounts — as a public persona he offered transcendence in a way that no one else from the business sector has offered for decades. Since his death Jobs has frequently been characterized as “Another Disney” or “Another Edison”. This is closer to the mark. He captured people’s imaginations and hearts like those businessmen did. It’s not that Jobs’s or Apple’s technology has incontrovertibly made the world a better place, but that it inspires imagination and, dare I say it, “subcreation”. Look at any creative sector today and it’s most likely dominated by Macs. That old 1984 Super Bowl ad still rings true for a lot of people. You’ve also sidestepped the issue of nostalgia, which, for many of us whose first computer was an Apple or a Mac, has a dominant role in shaping our image of Jobs. The joy we associate with having typed our first words onto a florescent green Apple II screen or with having drawn our first picture with a mouse in MacPaint is joy that we directly associate with the person of Steve Jobs. This isn’t pathetic, dude, it’s the joy and sadness that comes from glimpsing something more magical than ourselves.

You make some good points, my friend. And you’re 100% right about him capturing our imagination. I sold that aspect short (and perhaps ‘pathetic’ was too strong a word!). And I certainly agree that there’s an element of people mourning their childhoods. Lord knows those first glimpses of ‘magic’ are essential! So I fully take what you’re saying and I certainly don’t begrudge the inspiring effect he’s had on people. This clearly has Michael Jackson-like implications for some, and I wouldn’t want to deny their grief. I’m sad too.

I guess, from where I’m sitting, it just looks like it’s more than that, which the WSJ article really gets at. This event seems to have elicited a religious response from a group that tends not to think of itself that way (a group I consider myself a part of), and the force of it caught me off guard. If you’re right, and all these sophisticated people have found transcendence here, I don’t know, I guess I find that a little sad. Or alienating. I mean, do you think Disney or Edison carried the same sort of ideological weight or inspired a similar degree of personal identification as Jobs? I suspect not, which is really all I’m taking issue with. It could be a function of historical context, or it could be indicative of a slightly depressing (spiritual) hollowness, as I tried to suggest. It’s certainly not the end of the world, but it is revealing.

To me Jobs is Common Grace for people who don’t know where to place their worship. It may be inappropriate to worship Jobs himself, but the spirit he’s conjuring is something that lies dormant in many people: the yearning for something more. Crouch’s critique misses the forest for trees and smacks of pre-millenialism. He’s stomping his feet and saying “the world is getting worse, dammit! can’t you see?!” Well, the world is the world (Rom. 1), and there are special moments where people who don’t know God get a glimpse of his glory in art, design, music, etc. Jobs’s legacy isn’t about reversing the Fall of Man, and it isn’t appropriate in this context to inflict the spectre of Pelagius upon people who are captivated by beauty. To me, the unexpected, overwhelming response to Jobs’s death (in myself as well), is about recognizing that he brought a sense of beauty, magic, and the transcendent to the masses. In Jobs’s world you don’t have to be a Rockefeller to have a beautiful object in your life; it’s the democratization of beauty. In that, Jobs is also a uniquely American figure.

On common grace, see John of Damascus’ *Third Treatise on Divine Images* (trans. D. Anderson):

“The third kind of absolute worship is thanksgiving for all the good things He has created for us. All things owe a debt of thanks to God, and must offer Him ceaseless worship, because all things have their existence from Him, and in Him all things hold together. He gives lavishly of His gifts to all, without being asked; He desires all men to be saved and to partake of His goodness. He is long-suffering with us sinners, for He makes His sun rise on the evil and on the good, and sends rain on the just and on the unjust. He is the Son of God, yet He became one of us for our sake, and made us participants of His divine nature, so that ‘we shall all be like Him,’ as John the Theologian says in his catholic epistle.”

The thing, though, is: lots of Mac users were so superior about their use of the product. I’ve heard all kinds of look-down-the-nose remarks about my use of PCs – and how I was living “on the dark side” because I didn’t own a Mac. This is definitely another reason I didn’t like the product, actually – a reaction against the insufferable snootiness of some people congratulating themselves on being better than the rest.

These folks didn’t think of themselves as “the Common Man” at all – but as some sort of enlightened elite, actually. They were snobs, and Jobs was one, too, in fact. I think this was the reason I didn’t really like him much; still working that out. I know he didn’t care whether or not people could get the software they needed or wanted; it didn’t concern him at all. What mattered was having his loyal following. He played to the hip self-image, too, in the ads.

The machines are pretty, it’s true, though – these days, anyway, even if the first ones were clunky.

It’s interesting, isn’t it? I’ve never felt even a touch of the joy SFJ describes. I don’t like Macs, for a variety of historical reasons, and haven’t ever been tempted to buy one. Hated the often-broken AppleTalk, for one thing! DIdn’t like that Mac refused to you let us into memory, either, as if we were half-wits – and I hate those greasy, fingerprinty iPhones, too. Mac screens DO have great color display, though, I admit – the reason artists like them so much.

And I do understand the nostalgia aspect; I feel the same way about the first IBM PC and its massive 64K of memory. Wow, the amazing things you could do! 😉

Nothing at all to do with Bill Gates, though. From my point of view, if it hadn’t been Gates and Jobs, it surely would have been somebody else – so while I do find it sad that Jobs died so young, I’m just not feeling the worship, myself. In fact, I think we should go back to Alan Turing for our hagiography.

But then, I’m more enchanted by today’s open-source movement. I guess that probably means something….

The more I think about it, the more I think that the “emotional outpouring” resembles nothing so much as the similar outpouring for Princess Diana. Same sorts of things at work, I’d say: death at a young age, evoking the epically tragic; celebrity culture (big-time!); identification with a particular human being as icon and representative of a particular “cohort”; the mystery of charisma and character (and power and $).

SFJ, though, points out one really important difference: Jobs and Apple went after the education market, and caught kids up in their marketing web. On another website I read a tribute praising Jobs for “massively improving the quality of life” via Apple products, after somebody had pointed out that Apple never gave a cent to charity. The idea was that Jobs had been more than generous, via that “massive improvement” (an idea I must say I find totally delusional!).

Not to deny that some of these products really ARE beautiful; I agree that they are. I met somebody at Starbucks a couple of weeks ago to do some work, and he brought along his Mac Whatever. I actually gasped at one of its accessories – can’t remember which one now! – because it was so gorgeous. But that kind of thing was a late development – the result of many years of practice at a craft, or perhaps merely of hiring the right designers!. There are plenty of really nice product designs out there, though, and nobody knows or cares who was behind them – a fact that’s interesting to think about in itself.

Great article, great comments! This whole perspective resonates with me. I’ll a few of my thoughts for fun.

I think that people are calling Jobs a secular prophet, and some have implied that there is some kind of transcendance to him. There are classic gospel elements: he never cared about the money. He never did market research, he just envisioned and made great products. In that sense he was a mystic and a prophet – AND he did it in the context of agnostic capitalism! He was fired from Apple (death) but came back and turned the company around (resurrection). He said all of these things about being dead to the noise of the opinions of others to follow your true purpose. This reminds me of the parables of the treasure hidden and the pearl of great price.

People see liberation in technology; the 50’s and the sixties, pre-Jobs, were all about that too, in fact I think a case could be made that the bloom is off the rose now compared to the way people felt about the upward march of human progress back then. But people see empowerment and liberation in technology, and Jobs tapped into that very strongly. As The Onion has implied, maybe he was the last stalwart of American innovation. In a sense he was kind of a savior figure.

What we really see with all of this Jobs worship is that people need the gospel, they are starved for salvation and grace and transcendent purpose. So, they will create gospels that suit their preferences so they can go on liberated in their agnosticism and their supposed liberation from religious constraints. That’s my meager take on it.