I guess it’s unavoidable: once something becomes a buzzword it’s doomed. Perhaps that’s the whole point of calling something a “buzzword”. Like a celebrity with a rabid following, the quality or concept being described reaches a level of public esteem where there is more to be gained from tearing it down than embracing further. More attention, revenue, fame, credibility, etc.

I guess it’s unavoidable: once something becomes a buzzword it’s doomed. Perhaps that’s the whole point of calling something a “buzzword”. Like a celebrity with a rabid following, the quality or concept being described reaches a level of public esteem where there is more to be gained from tearing it down than embracing further. More attention, revenue, fame, credibility, etc.

Truth or falsity may not be completely beside the point, but it matters only so much when a bunch of pundits are roaming the interwebs hunting a sacred cow to mount on their wall. As if the first among us to register pushback–to notice the precise moment something good becomes something ultimate–wins the prize. The prize in his case being presumably some form of (short-lived) intellectual justification. Lord knows this is pot-kettle-black territory.

I mean, remember “authenticity”? “Mindfulness” is currently on the chopping block. No doubt “vulnerability” is next.

I don’t mean to suggest, by the way, that the criticisms involved are baseless. They never are. It’s just that the boomeranging arc of fashion tends to perpetuate the very all-or-nothing mentality it’s pushing back against and inspire more than a little cynicism in the process.

Probably goes without saying that religious communities are just as susceptible to this phenomenon as anyone. Today’s Thou Shalt will be tomorrow’s Thou Shalt Not. The only thing that doesn’t change is the self-justification impulse itself.

All this to explain why I had to physically restrain my eyes from rolling when the first of several articles hit my screen extolling “The Perils of Empathy”. Sheesh. The reason for this particular season is Yale psychologist Paul Bloom’s new book, Against Empathy, which CJ mentioned on Friday. For the sake of The Mockingcast roundtable, I finally caved and read them all, and I’m glad I did. There’s a lot more going on than clickbait effrontery.

The best of the bunch was written by Bloom himself for the Boston Review, where it’s accompanied by a number of responses from prominent thinkers. First off, Bloom defines what he means by the word:

The word “empathy” is used in many ways, but here I am adopting its most common meaning. It refers to the process of experiencing the world as others do, or at least as you think they do. To empathize with someone is to put yourself in her shoes, to feel her pain.

In general, empathy serves to dissolve the boundaries between one person and another; it is a force against selfishness and indifference. It is easy to see, then, how empathy can be a moral good, and it has many champions. Most people see the benefits of empathy as akin to the evils of racism: too obvious to require justification.

Empathy, of course, is traditionally distinguished from sympathy (a Victorian buzzword, apparently): the latter involves feeling for someone, the former with. He then goes on to list several qualifications, moving from the macro to the micro:

Empathy is biased; we are more prone to feel empathy for attractive people and for those who look like us or share our ethnic or national background. And empathy is narrow; it connects us to particular individuals, real or imagined, but is insensitive to numerical differences and statistical data. As Mother Teresa put it, “If I look at the mass I will never act. If I look at the one, I will.”

Our policies are improved when we appreciate that a hundred deaths are worse than one, even if we know the name of the one, and when we acknowledge that the life of someone in a faraway country is worth as much as the life a neighbor, even if our emotions pull us in a different direction. Without empathy, we are better able to grasp the importance of vaccinating children and responding to climate change. These acts impose costs on real people in the here and now for the sake of abstract future benefits.

What about relationships? Empathy might not scale up to the policy level, but it seems an unalloyed good when it comes to these intimate relationships…

A selfish person might go through life indifferent to the pleasure and pain of others—ninety-nine for him and one for everyone else—while for the empathizer the feelings of others are always in her head—ninety-nine for everyone else and one for her.

Strong inclination toward empathy comes with costs. Individuals scoring high in unmitigated communion report asymmetrical relationships, where they support others but don’t get support themselves. They also are more prone to suffer depression and anxiety.

In other words, empathy in the extreme can actually be a vehicle for loneliness rather than connection. You begin to expect, perhaps unconsciously, that others will empathize with you to the same extent that you do with them. When they don’t, you feel more separated than before. Moreover, as essayist Leslie Jamison notes in the responses, “empathy can fuel an ironic kind of self-absorption: the encounter with another person’s experience becomes another way of experiencing oneself.”

Under the auspices of helping, the extreme empathizer essentially colonizes another person’s emotional life–their hurt becomes your hurt, their outrage your outrage, etc. Often this is how we bear each other’s burdens, a commendable practice to be sure. But it can also be a way to distract yourself from your own emptiness or rationalize an overattachment. You might even say that feeling another person’s feelings can become a way of avoiding your own–a defense against emotion rather than a conduit for it. (It also sounds a lot like a description of an Enneagram 2, btw). Bloom goes on:

It is worth expanding on the difference between empathy and compassion. Imagine that the child of a close friend has drowned. A highly empathetic response would be to feel what your friend feels, to experience, as much as you can, the terrible sorrow and pain. In contrast, compassion involves concern and love for your friend, and the desire and motivation to help, but it need not involve mirroring your friend’s anguish.

As I write this, an older relative of mine who has cancer is going back and forth to hospitals and rehabilitation centers. I’ve watched him interact with doctors and learned what he thinks of them. He values doctors who take the time to listen to him and develop an understanding of his situation; he benefits from this sort of cognitive empathy. But emotional empathy is more complicated. He gets the most from doctors who don’t feel as he does, who are calm when he is anxious, confident when he is uncertain. And he particularly appreciates certain virtues that have little directly to do with empathy, virtues such as competence, honesty, professionalism, and respect.

Fair enough. In a clinical context, empathy only goes so far. The last thing anyone in a hospital bed wants to do is expend their limited energy managing other people’s emotions about what they’re going through. Bloom’s answer is to advocate for a form of “rational compassion, which doesn’t totally subsume the self”.

Wise as it sounds, this approach warrants a few qualifications of its own. First, as the NY Times noted in their review of the book, “Bloom has so much faith in reason”. But even presuming that our rational faculties are unbiased/-compromised, in the case of the relative with cancer, are we then to view our fellow sufferers as patients? People with problems for us to solve/fix? And what happens when the problem isn’t material so much as existential or spiritual?

Perhaps I’m succumbing to contrarianism myself, but the rational compassion route would seem to open the door to a different set of potential abuses: a whole lot of control-freakiness and paternalism. After all, many of us feel actively unhelped when someone steps in with unsolicited advice or aid before they’ve done the work of listening and/or empathizing–no matter how wise or reasonable that aid may be. Jamison draws this out in her response:

Specificity is what makes empathy so powerful. It is also what makes me distrustful of the distant compassion that Bloom advocates… [Because] this distance comes at a cost. We lose access to the particular contours of someone’s needs. Our offers of concern or aid can suffer as a result. Too much abstraction can mean we end up causing harm even when we mean to offer care.

In other words, let’s not throw out Frank Lake quite yet.

The timing of all this is pretty uncanny. Certainly the book was in the works long before Nov 9th, but one suspects that the ample press it’s getting has more than a little to do with the election results. As we all know, it’s a lot easier to empathize with your allies than your enemies. (To paraphrase our merciful friend, don’t even tax collectors do that?) One can’t help but harbor suspicions about any approach that props up an “us vs them” mentality.

Putting yourself in someone else’s shoes does not necessarily mean you validate their steps. To do so is not an exonerating act so much as a humanizing one. And that’s scary, especially when our self-justification is on the line. We’ll look for every reason not to “go there”. Heaven forbid anything disrupts the scapegoating process.

The timing is uncanny for a second reason, though. We are mere weeks away from that ultimate celebration of divine “with-ness” known as Christmas. The day when we commemorate the Incarnation, the beginning of God putting himself in human shoes sandals, bridging the great divide between creator and creature. Christmas is a testament to the reality that God’s love is not abstract or detached but specific and embodied.

And yet, Bloom is right. As wonderful and urgent and healing as empathy may be, it is not enough. We need more than God with us, we need God for us. A God who not only empathizes with those who would do him harm, but sympathizes with those who are subsumed in themselves and stuck in traps of their own devising. Who is close to the brokenhearted and justifies the ungodly.

Which is a long-winded way of saying, I’m glad the angel didn’t mince words:

“She will bear a son, and you shall call his name Jesus [or ‘God saves’], for he will save his people from their sins.” All this took place to fulfill what the Lord had spoken by the prophet: “Behold, a virgin shall conceive and bear a son, and his name shall be called Emman′u-el” (which means, ‘God with us’).

COMMENTS

6 responses to “Whatever You Do, Don’t… Empathize?”

Leave a Reply

Bart and Homer

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WGcwZsrfn7M

haha! i hadn’t seen that.

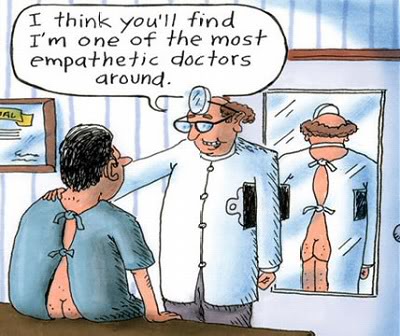

Glad I read this in full–it takes a decisive turn at “Are we to view our fellow sufferers as patients?” Really great response to a subtle but important topic–thanks DZ. (Also, the doctor comics…so weird haha.)

I wonder if good words only become buzzwords to those of us who are more cynical? I laughed when you talked about mindfulness being on the chopping block, because I’m always behind the times and “get into things” when the market’s already glutted with it (or it aired years ago hahaha).

“Empathy vs Compassion” and Sarah’s comments on the podcast about deeds in Judaism, reminded me of James 2: “Suppose you see a brother or sister who has no food or clothing, and you say, “Good-bye and have a good day; stay warm and eat well”—but then you don’t give that person any food or clothing. What good does that do?”. I don’t think I’m all that empathetic in the emotional sense. I cut my theological teeth on that Jewish idea that a good person does good deeds – not that I do an impressive number of good deeds, but that I do equate helping suffering with giving practical help – a listening ear, money etc.

I do think a kind of detatched compassion is the only thing that will give us even a chance of “loving our enemies”. But I’m not sure about whether abstraction necessarily removes empathy in a way that engenders “actionable” (another buzzword for the cemetery) compassion. Especially when there are so many atrocities happening to large numbers of people, the horrifying circumstances we hear about instantly on the internet, who are outside our sphere of influence (apart from giving money). Of course we should give money if we can, and there is the other whole issue of “compassion fatigue”. But I think I personally would develop more empathy AND compassion – and I would know someone was being helped and how – by finding something local and personal (de-abstraction, I guess). I have to admit that the quote about “our policies being improved” by becoming more detached set off my inner anarchist and fear of the totalitarian (left or right) “implementing good policies for the good of the people”.

It was great (as always) to be reminded at the end of your piece that God has worked for us and felt with us, even at those times when we suck at giving empathy or compassion and/or are feeling resentful because we think we’re not getting enough empathy from (insert person here who obviously doesn’t care about us at all) 🙂

Merry Christmas! The Christ is born. Emmanuel.

[…] humor this week: “Have More Empathy!” (which jabs at empathy’s strange current controversiality) by Chas Gillespie. At least just read to the “Bible pouch” line. You won’t […]