Thankful for this one from Caitlin Hubler.

“The” Old Testament does not exist. That is, there is no one version of the text. Although most of us encounter it in the form of a single, neatly bound book alongside the New, behind this veneer of simplicity lies a complex process of transmission, selection, and reconstruction. This problem of scriptural pluriformity has ordinarily been construed as a problem of access: if only we could go back in time to when these texts were first completed, then we would know the original wording and would not need to constantly compare later texts. Textual critics have for centuries compared variant manuscripts against one another in pursuit of the elusive original text (in German, the Urtext) of the Hebrew Bible. But groundbreaking archaeological discoveries of the mid 20th century called the very idea of one “original text” into question.

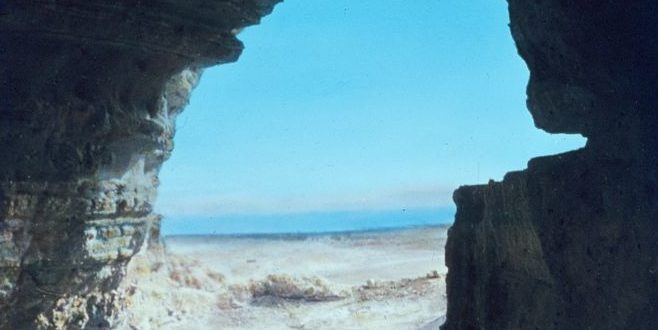

In 1947, Bedouin shepherds discovered the Dead Sea Scrolls, 931 ancient Hebrew and Aramaic manuscripts at Khirbet Qumran, in caves along the shore of the Dead Sea. These discoveries provided biblical scholars with a window into the development of the text approximately a millennium earlier than what previously available manuscripts allowed. The result was a very different picture of scripture in late Second Temple Judaism (a period spanning all the way from the so-called “intertestamental” period to the life of Christ) than they would ever have guessed to be the case.

It became clear that there was no point at which the text stopped developing and became “fixed” before the end of the Second Temple period. Different communities felt free to add to and delete from texts in various ways. There was yet no such thing as the biblical canon, nor was scriptural text organized into discrete “books.” The scriptures with which Christ himself was familiar would have looked quite different from our NRSV today, with its clear divisions and precise ordering of books.

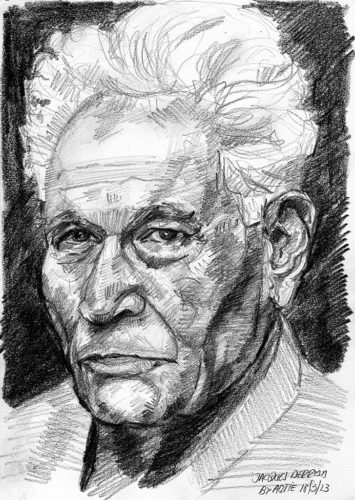

Any conversation around the nature of the scriptures of late Second Temple Judaism necessarily invokes another, more fundamental question: what is a text? Though the answer might seem obvious, closer scrutiny complicates matters. The philosopher Jacques Derrida loved to discuss the importance of the metaphors we use in discussing textual identity. He famously claimed that if we are to account for the changes texts undergo across time, making textual identity pluriform rather than uniform, then it makes more sense to discuss these texts “playing” as opposed to being “present.” The distinction between verb and adjective here is not insignificant: to speak of a text “playing” is to acknowledge its constantly shifting nature, that there is no point at which the text becomes stable and simply is. The identity of the text is not something to be located in its “center” (nor is it something that can be “located” at all); rather, it is inseparable from the text’s “movement” across time and space. Take this essay, for example: although it appears to you, the reader, to be a “fixed” text, it has undergone too much rewriting for its identity to be reduced to its most recent version. A more holistic way to speak of “this essay” is to reference the constant movement that has characterized it from the beginning.

Any conversation around the nature of the scriptures of late Second Temple Judaism necessarily invokes another, more fundamental question: what is a text? Though the answer might seem obvious, closer scrutiny complicates matters. The philosopher Jacques Derrida loved to discuss the importance of the metaphors we use in discussing textual identity. He famously claimed that if we are to account for the changes texts undergo across time, making textual identity pluriform rather than uniform, then it makes more sense to discuss these texts “playing” as opposed to being “present.” The distinction between verb and adjective here is not insignificant: to speak of a text “playing” is to acknowledge its constantly shifting nature, that there is no point at which the text becomes stable and simply is. The identity of the text is not something to be located in its “center” (nor is it something that can be “located” at all); rather, it is inseparable from the text’s “movement” across time and space. Take this essay, for example: although it appears to you, the reader, to be a “fixed” text, it has undergone too much rewriting for its identity to be reduced to its most recent version. A more holistic way to speak of “this essay” is to reference the constant movement that has characterized it from the beginning.

Relatedly, biblical textual critics relish discussion of whether the particular biblical book is “present” in a given manuscript or fragment. However, if Derrida is right, a text’s meaning cannot be reduced to the “presence” of one particular version (read: the “original text”); instead, any text’s meaning is an effect of the “play” of differences between versions.

Because of this added dimension to textual identity, a text’s meaning is constantly “deferred”. New text could always be added that would reshape the relationships between existing material and so produce new meanings. All texts, but particularly the “heavenly archives” of late Second Temple Judaism, are by nature incomplete. A certain orientation toward the future is created in such a textual world. More meaning is always “to come.”

***

Derrida also has a lot to say about that which is “to come”: the “à venir.” Most often, he uses the example of the human pursuit of democracy to illustrate this principle: the “democracy to come” is an imagined reality wherein the promises of justice and equity inherent in the word “democracy” are finally fulfilled. Though Derrida centers his analysis on the “democracy to come,” for him, the “to come” is more important than the “democracy.” Much of Derrida’s thought on the “to come” can be applied to the development of scripture: specifically, the ways in which late Second Temple Jews conceived of their holy texts.

Derrida also has a lot to say about that which is “to come”: the “à venir.” Most often, he uses the example of the human pursuit of democracy to illustrate this principle: the “democracy to come” is an imagined reality wherein the promises of justice and equity inherent in the word “democracy” are finally fulfilled. Though Derrida centers his analysis on the “democracy to come,” for him, the “to come” is more important than the “democracy.” Much of Derrida’s thought on the “to come” can be applied to the development of scripture: specifically, the ways in which late Second Temple Jews conceived of their holy texts.

A key element of Derrida’s understanding of the à venir is, as might be expected, counterintuitive. He is not speaking about a future point within time at which a long-awaited event will occur. On the contrary, Derrida says that when we speak of the “to come,” “the one thing we can be sure of is that it will never come.” It is always coming, which is another way of saying that it never finally comes. Some might despair at the prospect of eternally looking forward to something that never comes. For Derrida, the actual coming of the “to come” would be the real disaster: more like death than life. In the wake of such a coming, “What would there be to sigh and hope for? What would there be to dream of and desire? What would there be to pray and weep for?”

The longing for that which is to come is at least as important as the content of what is to come. This is why one of Derrida’s theological interpreters, John Caputo, defines the à venir as our “being-toward”: that is, it names a structural relation to the future that is in place regardless of what time it is. It does not demand that we patiently wait for a particular moment in the future, but that we intentionally position ourselves in a certain way towards the future: always hoping, ever expectant of the elusive à venir. It is not so much an “infinite progress toward an Ideal” as it is an “infinite intensification of hope.” As Caputo points out elsewhere, this is not dissimilar to prayer.

Indeed, to speak of the à venir is inherently quasi-religious in the sense that it draws upon a kind of promise from whatever (or whomever) is “beyond the horizon of forseeability.” Scripture in late Second Temple Judaism is like this: a promise that has been given and has yet to be (completely) fulfilled. A twofold movement is at work within such “promising words”: on the one hand, certain traditions are gathered and named by a community as part of a promise’s realization. On the other hand, there must likewise be recognition of the distance between the finite present reality and the infinitude of what the word has actually promised: what Caputo calls “deconstructive dissociation.” This dissociation is irreplaceable, because without it, the word becomes an idol: “A finite contraction of the unfinished promise of democracy to a particular figure or construction of democracy.” When one particular historical construction of democracy gets mistaken for the actual democracy in its infinite justice, the transcendent power harbored within the à venir is blocked off. In the same way, if late Second Temple Jews had insisted on one particular version of scripture as the archetype against which all others were to be compared, they would have missed out on much of what else God had to say.

Image credit: Arturo Espinosa Seguir.

COMMENTS

Leave a Reply