This one comes to us from Nancy Ritter.

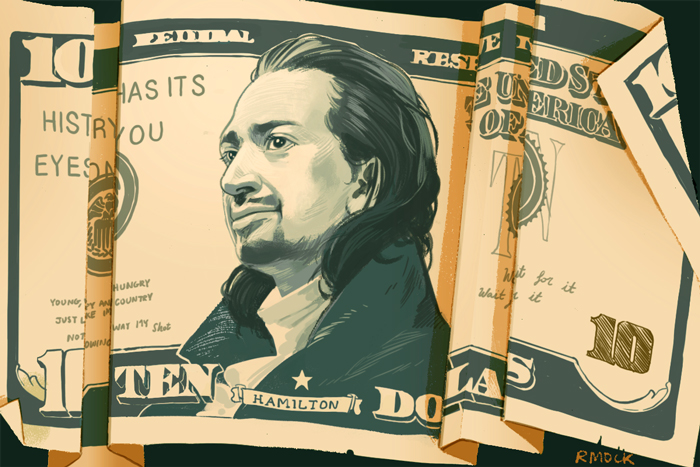

If you had told me in 2010 that in six years I would spend my Saturday nights watching a documentary on a musical about Alexander Hamilton or cheering its star Lin-Manuel Miranda as he hosted SNL, I would have scoffed at you. I was in high school when a friend showed me the video of the Pulitzer Prize-winning star performing at the White House for the Obamas, rapping about the life of Alexander Hamilton. I had been raised on 1776 and was consequently a loyal John Adams girl.

“I’m not into it,” I told her. “‘Bastard son of a scotch peddler and a whore’—you know John Adams said that, right? Hamilton was this self-made nobody who went on to centralize the government and make people like him poor. He sucks.”

Though retaining deep affection for John Adams, I’ve since eaten my words—and enjoyed every bite. I listen to Hamilton everywhere I go: in the shower, at work, in the car, on a run. I find myself working, writing, and running like Hamilton; I enter that data, write that cover letter, finish that mile as though the fate of the nation depends on it.

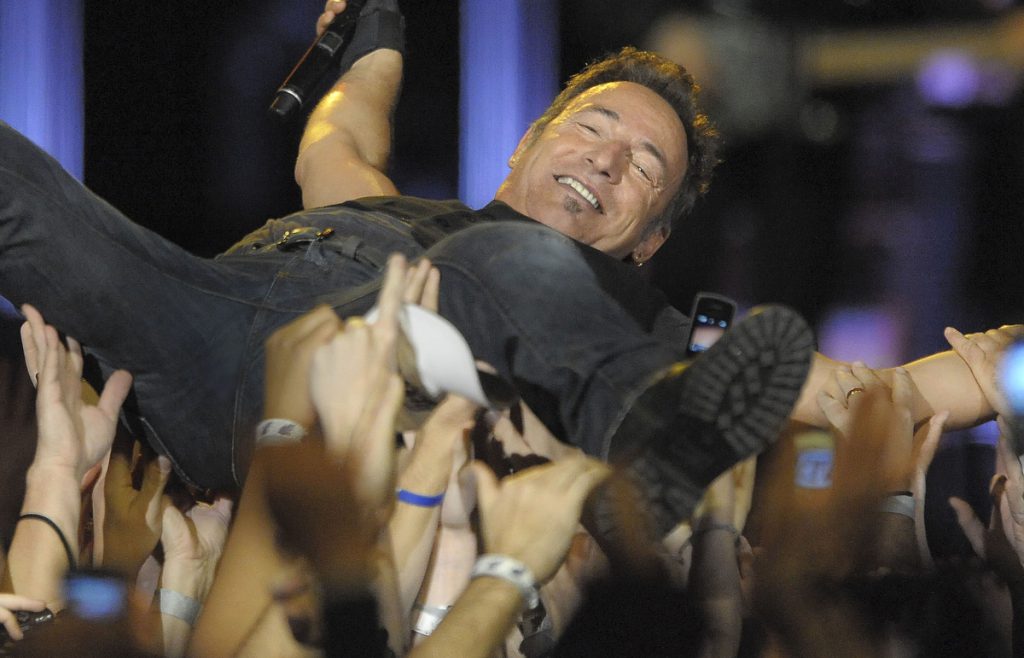

In many ways, Hamilton reminds me of another non-stop born runner and all-American immigrant dreamer: Bruce Springsteen. Whenever I’m not jamming to Hamilton on my jogs, I’m trying to figure out what a “tenth avenue freeze-out” actually is.

I’m sure I’ve lost most of you with that comparison. Hamilton is the hottest, hippest millennial hit; Bruce Springsteen is balding, baby boomer belting. Sure, he fills stadiums, just like Hamilton fills theatres, but it’s mostly middle-aged white dudes swilling BudLites and awkwardly shimmying to “Glory Days.” Plus, Hamilton repeatedly fertilizes on the Garden State, something that the jongleur of Jersey simply would not abide.

Hear me out, if only for your old man’s sake. Springsteen and Hamilton both arrived at a crucial moment in American history. In the early 70s, twentysomethings sneered at the false promises of Vietnam and the failed hopes of the 60s social revolutions. The same holds true of the world we millennials inherited: instead of successfully spreading democracy and boosting the economy, the Iraq War left many of us feeling hopeless and jobless. In both cases, the more critical, ironic distance gained from American imperialist stupidity, the better.

And then, against all odds and expectations, Springsteen and Hamilton thundered onto the scene. Young, scrappy, and hungry, neither had any patience for the disaffection and stalling—or indeed, any patience at all. Both are utterly lacking in “chill.” In her 2015 article in the Washington Post, Alexandra Petri celebrates Hamilton as bringing “the end of irony.” “Irony,” she declares, “has held us in its stifling tendrils long enough. We’ve exhausted so much effort trying to look like we’re not making an effort.” Hamilton, according to her, “has wasted no time trying to act as if it does not care…It’s not image-conscious. It’s genuinely passionate. And this is the source of its cool.”

That boundless energy also characterizes the Boss. Springsteen croons, yelps, grunts, and rasps. His concerts last over four hours; his songs number in the hundreds; his career spans four decades. “The man,” to quote Hamilton, “is non-stop.” And yet it is precisely this earnestness, energy, and eagerness that has lead millennials to reject him, per E.J. Dickson’s 2013 assessment in Salon: “I’m not going to proffer an in-depth sociological explanation for this sweeping wave of Bruce hatred, because I think ‘a widespread generational embrace of postmodern irony accompanied by a universal rejection of all that is honest and genuine and sincere pretty much says it all.” If both of these authors are correct, there’s some deep hypocrisy at work here, and it deserves investigation. How can we reject Springsteen for his sincerity, and yet embrace the same qualities in Hamilton?

Perhaps it’s the inevitable association with our fathers. Most people, Dickson admits, associate Springsteen with their dads. I certainly do: I know every word to “Spirit in the Night,” “Rosalita,” and “Badlands” thanks to years spent watching my dad car dance from the back seat on family road trips as I tried to read Harry Potter. And let’s face it—most people who argue for a need to “reverence our forefathers who went before us” are pundits who see the apocalypse in selfies, Obergefell, the Obamas, and Snapchat. But isn’t this precisely what Hamilton asks us to do? Reverence our fathers? Remember that the faces decorating the bills and busts were living, longing human beings just like we are?

This is not to say that Springsteen and Hamilton are without their flaws. Can you be without flaw when you have such valiant, “vaulting ambition”? Petri identifies the source of Hamilton’s endless enthusiasm: his passion about his own legacy. Hamilton cares so much what the history books will say about him that the ethics of the everyday often escape him—especially where women are concerned. Hamilton woos the demure, wealthy Eliza Schuyler, overlooks his true soulmate in her sister Angelica, and breaks both their hearts through his liaison with Maria Reynolds. The same holds true of Springsteen: by his own admission, Born to Run was his attempt “to make the greatest rock and roll record ever made.” He succeeded—but not without cost. If the songs are to be believed, the Boss leaves a long trail of brokenhearted Marys, Candys, and Sherrys behind him. (Not to mention his highly public divorce from Julianne Phillips, painfully documented in Tunnel of Love.)

Plus, one could easily argue that the sheer amount of wealth Hamilton and Springsteen have accumulated is a betrayal of the populism both supposedly represent. Hamilton, although ostensibly a musical by the people and for the people, charges hundreds of dollars a head. Springsteen has made millions of dollars. A recent article in the New York Times highlights how the towns mentioned in Springsteen’s songs are pretty evenly divided between Trump voters and Hillary voters, and NPR noted how Hamilton, though played by brown actors, plays almost exclusively to a white audience.

Ultimately, neither falls comfortably along liberal or conservative lines—and neither does the country they represent. As the Founding Fathers attempted to create something new, they referenced the classical Roman authors and statesmen. Springsteen fused already existing jazz, soul, and rock styles to create a sound all his own. Lin-Manuel Miranda, who started his career working at McDonald’s, based Hamilton on a biography by Ron Chernow, a wealthy New Yorker educated at Yale and Cambridge. The most traditional Americans are those who eschew tradition and light out for the territories, who speed down the highway, chasing “the runaway American dream.” Those with restless, hungry hearts—those who, no matter how many amazing things they achieve, “will never be satisfied.”

Of course, this hunger and inability to be satisfied is not merely an American characteristic—though few countries have enshrined it as a national characteristic as devoutly as we have. It’s a universal human experience. I experienced it pretty painfully myself a few months ago when I was teaching abroad. I lay in bed in my apartment in Beit Hanina, Jerusalem, Israel-Palestine, weeping. I was desperately homesick. I despised the dry desert air; I missed DC’s swampish humidity. I was over the falafel, and hankered for a Big Mac. I hated the wall; I wanted the open road.

So I turned on some Bruce Springsteen. “Thunder Road,” specifically. I nestled in among the sheets and let the tears roll down my face as a mournful harmonica, an electric guitar, and that unmistakable, raspy voice wooed me through my crappy computer speakers:

You can hide ‘neath your covers and study your pain

Make crosses from your lovers, throw roses in the rain

Waste your summer praying in vain

For a savior to rise from these streetsWell now, I ain’t no hero, that’s understood

All the redemption I can offer, girl, is beneath this dirty hood

With a chance to make it good somehow

Hey, what else can we do now?

Except roll down the window and let the wind blow back your hair

Well, the night’s busting open, these two lanes will take us anywhere

We got one last chance to make it real

To trade in these wings on some wheels

Climb in back, heaven’s waiting on down the tracks…Oh oh, come take my hand

We’re riding out tonight to case the promised land

Oh oh oh oh, Thunder Road

Oh, Thunder Road, oh, Thunder Road…

Of course, this longing for the “promised land” was both deeply ironic and deeply hypocritical. Springsteen and Hamilton both place their promised land squarely in America: Hamilton declares in the stirring anthem “My Shot” that he and his fellow revolutionaries will “roll like Moses, claiming our promised land.” But it was my rejection of America as the secularist, materialist, rationalist substitute for the promised land that had driven me to move to Jerusalem in the first place. I yearned for something more spiritually satisfying than my retail job and office internship. The city where faith is at its liveliest and deadliest seemed a likely solution.

And yet there I was, lying in bed, listening to Bruce Springsteen, crying and longing for home. What’s more, the longing didn’t even improve after I did get home. Two months after returning to the land and the people that I love, I found myself crying and yearning again, this time on my best friend’s couch. She comforted me as best she could, but it didn’t help. I left her house and got in my car. E Street radio was on, and Springsteen was singing a muted, acoustic version of “Thunder Road” to a live audience. I knew I couldn’t just drive home and crawl in bed, so I got on the highway and drove into towards downtown DC—knowing that my search for America, for satisfaction wouldn’t work, but unable to help myself from searching anyway.

There’s only two real ways to explain this hunger. One is the way of the ironists, the Aaron Burrs, the Bruce haters and Hamilton skeptics: to give up the hunt, abandon the quest, stop searching. The longing is an adolescent attempt to avoid the fact of our mortality. It’s the easier explanation, and it’s the one I often implicitly choose when I idly scroll through Facebook, when I eat Nutella and watch rom-com clips on Youtube, and when I drink box wine to help myself get to sleep at night.

The other explanation comes from another immigrant, another adulterer, another restless, hungry heart who has passed into the pantheon of “dead white guys.” St. Augustine of Hippo was born in 354 A.D. in a small town in northern Africa, thousands of miles away from where history was happening. His hard work and brilliant mind eventually took him to the greatest city in the world: Rome of late antiquity, where Christianity was one faith among many. Augustine flitted from cult to cult and woman to woman; his famous prayer “Lord, make me chaste, but don’t do it yet” could well be the prayer of Springsteen or Hamilton.

Eventually, he moved to Milan and met Ambrose, the city’s bishop, whose kindness, virtue, and wisdom eventually lead Augustine to a dramatic conversion experience. This experience Augustine recounts in the Confessions, the first autobiography in the western tradition. The book opens with Augustine movingly writing of the restlessness of the human heart in a prayer:

You move us to delight in praising You;

For you have formed us for yourself,

And our hearts are restless till they find rest in you.

God—infinite, immortal, incomprehensible—alone can satisfy the infinite, immortal, and incomprehensible longing of our hungry hearts. And our only true home is the promised land whose capital is the city of God. After the Confessions, Augustine wrote his magnum opus, The City of God. As the Roman empire began to crumble and people began to panic, Augustine reminded Christians that they had no business giving way to fear. Those who believe have dual citizenship: temporal citizenship in the city of men, and eternal citizenship in the city of God. Loving and fighting for the city of men is not wrong—indeed, in its proper place, it is a great virtues. But the love of and fight for the temporal homeland should never eclipse the love of and fight for the true homeland.

The flaw of Springsteen, of Hamilton, and indeed, of America itself is not that it longs, hungers, and runs. It is rather the object of our longing, our hungering, and our running that constitutes our flaw. America, ambition, and rock ‘n roll are all glorious, good gifts—but they cannot lastingly satisfy independent of their Giver. We were all born to run, and none of us will ever be satisfied on this earth as it now stands. We can deny the desire and refuse the race. We can be like Springsteen’s Mary and Hamilton’s Burr and spend our lives waiting for it on the safety of the porch. Or we can make the long walk from the front porch to the front seat, knowing that “the door’s open but the ride ain’t free.” We can take our shot, even at the risk of missing the mark. And we can pray with Augustine—who, after all, said that “he who sings, prays twice”:

You never go away from us, yet we have difficulty in returning to You.

Come, Lord, stir us up and call us back.

Kindle us and seize us.

Be our fire and our sweetness.

Let us love.

Let us run.

COMMENTS

One response to ““Young, Scrappy, and Hungry”: The Restless Hearts of Hamilton, Bruce Springsteen, and St. Augustine”

Leave a Reply

Yes. The flaw is not in the longing, but the objects for which Springsteen and Hamilton, and the whole lot of us, long.

But a question: Was Augustine white?