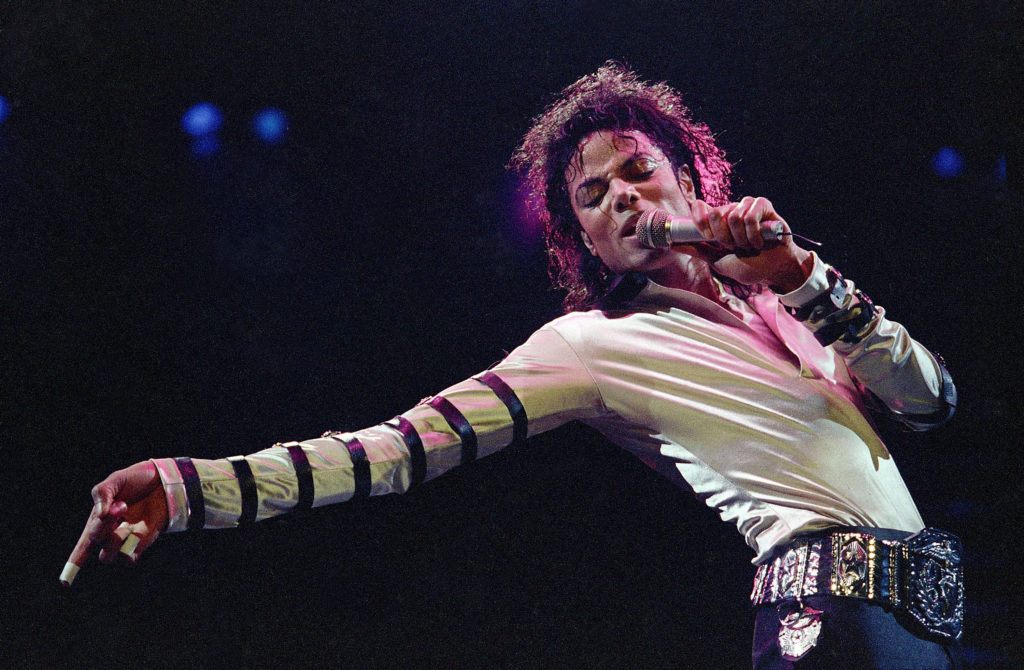

In honor of the King of Pop’s 60th birthday, here’s the entire MJ chapter from A Mess of Help.

I don’t remember where I was when the Berlin Wall fell. I can’t tell you what I was doing when I heard that my grandfather had died. I’m a little shaky on the details of my wife telling me she was pregnant with our second child. But I can recall with crystal clarity the day Michael Jackson died. It was mid-afternoon on June 25th, 2009, and I was sitting in a Manhattan church basement, working in a windowless office. I got a ‘gchat’ message from a friend, asking me what I made of the news about MJ. She knew I was a Jackson obsessive. What news, I replied. Five minutes later I was legging it to my apartment where I stayed for hours, glued to the TV, until Jermaine issued that fateful statement. I didn’t go to work the next day.

We don’t get to choose what makes us feel sad or shocks us. We simply respond, and those responses often betray embarrassing sensitivities and values. A close relative had passed away a few months before Michael, and at her funeral I had wanted so badly to feel worse. But the emotions simply weren’t there. I found the numbness alienating.

Not so the day Michael died. This time, it was my wife who was alienated. I had refused to take a sick day after that, er, disillusioning case of violent, Korean BBQ-related food poisoning a few weeks prior, but this warranted convalescence? Whom had she married? Truth be told, the force of the wallop took me by surprise as well.[1] I’m still trying to figure out what was behind the funk, both Michael’s and my own. This essay collects a few such theories.

Michael Jackson was many things to many people. To his countless fans, he was the immortal King of Pop who could do no wrong. To those who had proven immune to his charms (or come of age after 1990), he was a cautionary tale about the dangers of child celebrity. Some considered him a pioneering black American artist, others a freak show who betrayed his race. Depending on your point of view, Michael was a one-man corporation with brilliant business instincts or the embodiment of the most vulgar kind of pop commercialism. Supporters championed him as a misunderstood beacon of human goodness; detractors decried a predatory monster. Pundits called him the most disturbed pop-cultural figure of the last fifty years. To a sober few, he was simply a talented, if troubled, entertainer whose music can still get a party started. And then there are those to whom he would always be little Michael, spinning around the Ed Sullivan stage like a miniature James Brown, asking for “One More Chance”.

After Michael died, an impressive wave of nostalgia hit, and the divergent personae briefly seemed to merge. Death cemented his status as a one-of-a-kind icon, but it also put a fixed distance between him and the public. You could worship the guy or revile him, feel sorry for or judge—anything but identify. As one writer put it in 2014:

“Empathy is the quality that’s missing from virtually everything ever written about Michael Jackson. We glorify him or we vilify him or we pity him or we take his changing appearance and we use it as fodder for theories about race and gender—the highbrow equivalent of the objectification you’ll find in the tabloids. We do all of this, but we do not attempt to understand him. The idea of Michael Jackson as a human being remains a radical notion.”[2]

Make no mistake: Michael was not lying when he famously told us he was “not like other guys” (“Thriller”). But that does not mean his life and music can’t tell us something about “the man in the mirror”. To the contrary, there is much of value to be gleaned from Michael Jackson—some of it inspiring, some of it uncomfortable, and all of it ultimately helpful. Many a disco could be burned out unpacking the ‘Gospel according to MJ’; out of respect for the concise genius of his early hits, though, I’ll restrict the focus to the three themes that hit me most powerfully in the months following his loss: reconciliation, relief, and rebirth.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SA3-mVGc8wA

Have You Seen My Childhood?

Michael’s gifts were apparent from an early age. He joined his brothers in The Jackson 5 at the age of seven, he took over most of the lead vocals by the time he was eight, and the group won amateur night at The Apollo in Harlem when he was nine, catapulting them into the national spotlight. He was eleven when “I Want You Back” became the first of their string of smash hits. Wikipedia can give you the chronology. Suffice it to say, young Michael displayed an instinctive understanding of phrasing, dancing, and performing that men with years of training could not equal.

Michael’s talent was actually so prodigious that, by all reports, it created negative feelings toward him. His brothers resented him for being so good, for doing what they could not and making it look easy.[3] You can hardly blame them. After all, it’s not as though he had done anything extra to deserve any of it—he had simply been born. Just like Jackie, Tito, Marlon, and Jermaine, he was son of a crane operator in Nazareth Gary, Indiana. But the discrepancy in talent put a wedge between Michael and those closest to him.

Furthermore, his relationship with his parents was inverted: as the primary driver of their financial success, he provided for them rather than vice versa. His father Joe was their manager, which means that Michael was his boss. Disproportionate giftedness fueled the loneliness that would dog him his entire life.

The solitude was compounded by circumstances beyond the family, too. From age nine to age eighteen Michael worked pretty much all day, everyday, recording when he wasn’t touring. His parents were Jehovah’s Witnesses who did not believe in Christmas or birthdays, which meant there was little excuse for taking breaks (or pursuing meaningless fun). He was taken out of school at seven, educated by tutors. To hear him tell it, Michael didn’t have any playmates outside of his family. In his whitewashed autobiography, Moonwalk, he characterized his upbringing as follows:

“There was a park across the street from the Motown studio, and I can remember looking at those kids playing games. I’d just stare at them in wonder—I couldn’t imagine such freedom, such a carefree life—and wish more than anything that I had that kind of freedom, that I could walk away and be like them.”

Yet the Jackson 5’s music evokes no emotion more consistently than joy. Hits like “ABC”, “The Love You Save”, and “Mama’s Pearl” set a standard for youthful exuberance that has seldom been surpassed. The Jacksons’ predilection for contradiction would only blossom over the coming years.[4]

Perhaps, then, it should come as no surprise that once he turned twenty-one, Michael stridently set out to reclaim his childhood. He could hardly have crafted a clearer mission statement than the 1996 song “Childhood”, in which he tells us, “it’s been my fate to compensate / for the childhood I’ve never known”. The song may not be his edgiest moment—it may be his most treacly in fact—but it confirmed what many had suspected for years: that Michael viewed childhood as paradise lost, full of the unconditional love, joy, and freedom which his precocity had denied him. There was nothing arbitrary, in other words, about his decision to fill his primary residence with amusement park rides and dub it Neverland.[5]

Perhaps reconciliation—in the sense of restoring harmony to a fractured situation—is not too strong a term for what Michael was after. The ways he went about reconciling his childhood may have been strange and sometimes unsettling, but in light of, say, Christ’s words in Mark 10, perhaps his strategy wasn’t as deranged as it sometimes appeared. [6] And even when things did get weird, it was never for weirdness’s sake. His choice of friends may have seemed unconventional, but there was empathy behind it. Michael would make a point of reaching out to other child stars, like Emmanuel Lewis, Macaulay Culkin, Kris Kross, because he knew what they were facing. If we take Michael at his word (and many don’t), out of the wounds of the past flowed compassion and kindness.

Of course, a desire for personal reconciliation isn’t limited to child stars or those who have suffered injustice or tragedy. None of us escape our formative years without something happening to us that we wish had not. We all carry some hurt with us into adulthood, a wound that resists healing. Maybe part of the motivation behind our career has to do with righting a past wrong, such as earning the money we lacked as a child or marrying someone strongly resembling a parent who withheld affection. Maybe we play out the same scenarios in our relationships over and over again, always trying to engineer a more positive outcome than what experienced in our upbringing. Maybe Michael is not so different from his loyal subjects in the kingdom of pop.

Sadly, the similarities extend beyond the realm of desire. Our attempts to reconcile the past often meet with the same outcome that Michael’s did. Each additional zero in our bank balance, each fresh notch on our belt, only underlines how elusive ‘enoughness’ is. Indeed, the older Michael got, the more fixated he seemed to become on recovering his childhood, not less. He could not engineer reconciliation any more than the rest of us. Something more than determination (and gobs of money) is required if we are to achieve peace with our past. Not even a personal amusement park will do the trick.

Someone Put Your Hand Out

If much of Michael’s personal life as an adult was spent trying to get back to childhood, much of his professional life was spent trying to get back to Thriller, to live up to its success and surpass it. We’ve skipped a few years in the story, but the details are well-known. Soon after The Jacksons left the Motown label (for Epic), Michael embarked on a solo career in earnest, writing his own songs, choreographing his own dance moves, producing his own videos, and wearing his own clothes.[7] The trio of blockbuster albums he recorded with Quincy Jones, 1979’s Off the Wall, 1982’s Thriller and 1987’s Bad, met with unprecedented worldwide success, making Michael a household name from Lincoln to Liberia. Thriller became the best-selling album of all time, and the King of Pop was born. But so was an inflexible Law of Perfection which would prove just as merciless as the news media that would scrutinize his every move in the years following its release. It is no coincidence that the apostle Paul wrote that those “who rely on the works of the law are under a curse” (Galatians 3:10).

Which brings me back to my own journey with Michael. I was still a toddler when Thriller came out, and like many of my generation, my first conscious Jackson experience came at Disney World via Michael’s much-hyped 3-D collaboration with George Lucas and Francis Ford Coppola, Captain Eo. My seven year-old self was as powerless to resist its charms as the Supreme Leader’s minions were to resist Eo’s energy beams. A debonair space pirate (and his furry friends), devoted to “bringing freedom to the countless worlds of despair”—in this case a legitimately frightening H.R. Giger-designed landscape—what was not to like?[8] I was hooked.

Of course, I had a long way to travel (through my father’s record collection) before I’d be ready for synthesized bass and syncopated hiccups. Bad came out on the heels of Captain Eo, though, and struck enough of a chord that when Dangerous finally arrived in 1991, the pump was primed. In fact, Dangerous became the very first compact disc in a collection that would eventually take up a room of its own. Some would say I boarded the train just as it was crashing, but they would be gravely mistaken. HIStory had yet to be written.

I became a monster fan, the kind who would defend Michael to total strangers at parties. I took it personally when people insulted him or assumed the worst without looking into the controversies for themselves. I was excited about the rehabilitation that had begun with the 25th anniversary of Thriller; the public was finally ready to embrace him again. I was convinced that the This Is It tour would give Michael the confidence to finish the material he had been working on, which I knew in my heart would be a masterpiece. Then June 25th happened, so suddenly, and he was gone. I don’t think I will ever get over it.

For a while afterward, it was gratifying to see MJ recognized for something other than kookiness. But as happy as I was about the renewed enthusiasm, there was “another part of me” that resented the revival and saw it as fair-weather friendship. Where were all these people when he needed them, I wondered? Where were they in the 90s?

The 1990s were a fractious period for Michael, a time when the irritating but largely harmless tabloid coverage took a dark and persecutory turn. It was the decade when his personal problems and eccentricities first overshadowed his artistry. Not surprisingly, relief from pressure and accusation would become a major theme of his 90s work (and beyond), perhaps the primary one.[9]

Some would theorize that Michael experienced a degree of success with Thriller and Bad such that the public felt entitled to judge him—“the price of fame”, as he would later sing.[10] Everyone on the planet developed an opinion about Michael Jackson. It may have been, “He has nothing to do with me”, or maybe, “I love his songs but can’t stand to look at his face”, or maybe, “It’s all been downhill since The Jackson 5ive cartoon went off the air in 1972”. Whatever the case, we can safely say that he did not benefit from public indifference.

But the 90s were also the period when Michael produced some of his greatest and most important music. This is an unpopular opinion, and it’s probably more informed by my abiding interest in Christian theology than I would care to admit. But the truth is, there is no more compelling or compassion-inducing instance of how judgment, demand, and scrutiny—what we might call the Law—play out in everyday life than Lisa Marie Presley-era Michael Jackson.[11] Which is not to suggest that the Law was absent in his life before this point. The nostalgia for the childhood he never had—and the judgment-free period it represented—was very much linked to anguished relationship he maintained with judgments of the public.

Take, for instance, “Will You Be There?”, released just as the decade was dawning, known to some for its (regrettable) association with the movie Free Willy.[12] After a ridiculously over-the-top choral intro, we hear Michael plead with a gospel choir for love and understanding, crying “I’m only human!” over and over. I defy you not to be moved.

The exhaustion continues in “Black or White”, where he (and Slash!!) tells us, “I’m tired of this devil / I’m tired of this stuff / I’m tired of this business / Sew when the going gets rough”. What sounds like an uplifting coda on the single is actually Michael talking about how “it’s tough for you to get by”, no matter your color or background. Perhaps Michael is milking the juxtaposition for artistic purposes, or perhaps he is simply singing out of both sides of his mouth; he cannot help but try to appease the populace with audio candy even while venting his frustration at the very system that demands that he do so. Either way, the discrepancy gives the song more dimension than might initially be apparent.

The final masterpiece on Dangerous, “Who Is It”—another in Michael’s unparalleled series of paranoid anthems (“Billie Jean”, “Smooth Criminal”, “Somebody’s Watching Me”, “Is It Scary”, etc.)—contains the confession, “The will has brought no fortune / Still I cry alone at night / Don’t you judge of my composure / cause I’m lying to myself”, and then, finally, “I can’t take it cause I’m lonely!” It is the sound of a man hanging by a thread. Of course, elsewhere on the record we encounter “Heal the World”, a song so sappy it makes “Ben” look edgy.[13]

Every Day Create Your History

As dark as Dangerous gets, it doesn’t hold a candle to the second disc of 1996’s HIStory. HIStory disc two, or HIStory Continues, finds Michael at his most open-veined and broken, his Plastic Ono Band, if you will.[14] It opens with what may be the all-time greatest MJ single, “Scream”. Over a chorus of breaking glass and slamming doors, he and his sister Janet yell, “stop pressuring me / just stop pressuring me / stop pressuring me / [you] make me want to scream” before begging, “somebody please have mercy cause I just can’t take it!” It is hard to see how anyone who has listened carefully to “Scream” could argue that it is not operating on a more profound (albeit less fun) level than “Beat It”. Sadly, Michael made it impossible for us to just listen—we had to look too, and his appearance by this time had become truly bizarre.[15]

The second track on HIStory is another blast of disaffection called “They Don’t Care About Us”. Then comes the inspired “Stranger in Moscow”, the loneliest of all his lonely songs, where he mentions his “swift and sudden fall from grace” and asks, “how does it feel / when you’re alone and you’re cold inside?” He also makes references to Stalin’s tomb, the KGB, and nuclear Armageddon. We are a long way from “Rockin’ Robin”.

But it hardly ends there. The centerpiece of HIStory is certainly the most ambitious anthem in a career full of them. “Earth Song” has been shoeboxed as an environmental song, but that label doesn’t remotely do it justice. A more accurate description would be the one Joseph Vogel gave it: “a lamentation torn from the pages of Job and Jeremiah, an apocalyptic prophecy that recalled the works of Blake, Yeats, and Eliot.”[16] That is, “Earth Song” is not simply the dark, grown-up flipside of “Heal The World”; it is a prayer directed at a God whom Michael views as both absent and culpable for the planet’s suffering. (Midway through he asks, “What about all the peace that you pledged your only son?”) Over the course of seven minutes, Michael cycles through every grievance imaginable, from crying whales to the Holy Land to death itself, while the background singers implore over and over, “What about us?”

The scope might be (more) laughable were Michael’s voice not so agonized, his melody so entrancing, or, importantly, if the lyric had contained even a hint of resolution. Such was his state of mind at the time that Michael wisely chose to let his plea stand, its unrestrained expression being the sole counterintuitive source of its uplift. The song was a worldwide smash—everywhere except the USA, that is—but in the context of the record, it’s hard not to hear “Earth Song” as a brilliant smokescreen for Jackson’s more pressing concern, not “what about us?”, but ‘what about me?’

One could go on and on. Suffice to say, HIStory remains a towering achievement of superego, Michael’s misunderstood masterpiece of misunderstanding as well as a visceral testimony to what the apostle Paul wrote in 2 Corinthians: “the letter kills” (3:6).[17] The fruit of the Law of Perfection—“thou shalt be the King of Pop”—in this case was alienation and loneliness, anger, depression, writer’s block and, yes, in all likelihood, more sin.

Conventional wisdom holds that one of the most common responses to judgment involves shifting blame, either outwardly or inwardly: to “the man in the mirror” or the Billie Jeans of the world. If those who are prone to guilt cast themselves as villains when put upon, then those who are prone to anger cast themselves as victims. In the 90s it became increasingly apparent that Michael had chosen the latter route. Of course, victim and villain are often different sides of the same self-justifying coin; the truth usually lies closer to what we find in the video for “Thriller”, where Michael is both the hero who saves girl at the end and the monster from whom she must be saved. On his curiously ignored final album Invincible, Michael boasts about his, you guessed it, invincibility, and how we should feel threatened by his all-encompassing dominance. He then spends the rest of the record crying out for relief and mercy.[18]

Again, Michael’s complicated relationship with judgment is not dissimilar to our own. Our circumstances may not approach Jackson-ite extremes, thank God, but all of us live under some form of perceived judgment. I know I do. The standard we are suffering under may not be that of platinum record sales or global reputation. It may be parental or spousal approval. Perhaps we are hoping for mercy from the job market or the dating scene or the social register. Perhaps we see downward mobility as a fate worse than death. Whatever the venue—petty or not—who couldn’t use a little relief? From ourselves if not others, to say nothing of a Creator whose “property is always to have mercy”. Thank God.

The burden of being Michael Jackson is something no one should ever have to bear. That he would crack up under that kind of pressure is not wacko in the slightest. It may be a small mercy that his talent did not abandon him during his struggles, but it is a mercy nonetheless—and in a life that contained far too little of it, “no message should have been any clearer”.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iHaGfdE3vIY

It Don’t Matter If You’re Black or White (or Both)

If appeasement is one approach to the crushing expectations of an audience or self-image, a popular alternative, or next step, is flight. That is, when it becomes clear that no amount of striving can silence the voice of the Law, we first flee it, moving across the country or taking a new job. Then, when that doesn’t work, we try to flee ourselves, sometimes (tragically) via self-harm. Fortunately, Jackson took a more creative, if still ineffective, route; in addition to improved performance, he opted for an improved self.

Indeed, no treatment of Michael Jackson would be complete without mention of his physical metamorphosis. This topic has understandably proven to be a lightning-rod for theorists, armchair and academic alike. As opposed to his childhood and the judgments of the public, Michael didn’t comment very much on his appearance, and when he did, the reports were always, shall we say, evolving. It was clearly a sensitive spot. So part of what follows will necessarily be conjecture and have more to do with the ‘eye of the beholder’ than the Moonwalker himself.

Theatre critic Margo Jefferson has written about the subject of Michael’s face with particular eloquence and insight:

“Most people want an improved version of themselves, or at least something they could call a beautiful relation. Michael’s face is in another zone altogether. It has nothing in common with him anymore. We look. We shiver. We want to turn away. He was not supposed to expose this kind of need. What is it: Self-hatred? Fear and loathing of human beings? A passion to escape the conditions of life and human exchange so fierce that he is willing to be reborn through science? The desire for a kind of perfection most of us cannot see and that he will not share with us? A will to change reality that is a postmodern version of hubris?”[19]

Let’s go with “F. All of the Above”. Hubris is written all over it, but so is self-recrimination. And so are narcissism and despair, transcendence and retreat, self-sabotage and self-glorification, even ingenuity and vision. No one can know for sure what lay “behind the mask”. All we know is that the transformation happened and that it was very much in proportion to the scale of his other ambitions. It was proof, perhaps, that the courage and perfectionism that marked all MJ undertakings was not without a downside. In fact, what made him great may have also contributed to his demise. It is impossible not to theorize.

Suffice it to say, like his artistry, there was nothing prosaic about Michael Jackson’s image—which may have been inevitable when all you know of life is performance (Jefferson suggests elsewhere that Michael was always performing, or rather, that he couldn’t not perform). Whatever the underlying psychology, he took the Law of Who You Must Be an uncomfortable step further than any celebrity ever has—more than a little ironic, since he was the one who, as the most famous person on the planet, had redefined the parameters of Acceptable and Cool. Alas, it is not always enough to be the best. You must be perfect (as your father in heaven is perfect).

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yjDnRwYtg0E

On the surface, plastic surgery seems to have provided Michael with a way to rebirth himself in a more perfect way. To play God and right what he perceived as physical wrongs.[20] We know for certain that Michael did not hesitate to take advantage of an accident on the set of The Wiz (1978) to redress the ‘big nose’ scars of his childhood and fashion a face where they would (theoretically) no longer apply. Over the years, the scope crept. Vitiligo or not, his skin color would slowly suffer a fate similar to that of his nose. Then his chin, his hair, his eyes. Maybe racial and sexual identifiers were equally painful to him. Maybe Michael was dying to transcend all the biological labels he’d ever been saddled with, and felt he had the power, or even the responsibility (!), to do so. He would “make [the world] a better place”, starting with his profile.

Perhaps there was also some genuine self-loathing as well. The man who owned the rights to “All You Need Is Love”—and every other Beatles song—may have had the love of billions, but apparently could not love himself. Who knows.

Of course, if we are honest with ourselves, who has not thought about what we would change about our appearance if someone were to offer to pay for our surgery and assure us that no one would find out? You don’t have to be religious to covet a do-over in life—to not be happy with who you are, with how you have been made to be, with what has happened to you. The appeal of new life, rebirth, baptism, whatever you want to call it, is universal. When taken to its Jackson-ite extreme, self-deification may look an awful lot like insanity, but the roots are recognizably commonplace.

Or we could read the situation a bit more generously. This is the man who wrote “We Are the World”, after all. Perhaps the surgeries were not a negation of who he was as a black male so much as a (misguided) assimilation of everything and everyone he wanted to reach. Instead of settling for an ideal version of himself, maybe Michael was seeking to become an ideal version of everybody, i.e., to incorporate every possible element into his appearance, just as he had done with his audience and art. To embody the unity he yearned for, in other words. Indeed, categories of race, gender, sexuality, even species, hardly seem to apply to what MJ became. In 1987, artist Keith Haring penned a journal entry that put it this way:

“I talk about my respect for Michael’s attempts to take creation in his own hands and invent a non-black, non-white, non-male, non-female creature by utilizing plastic surgery and modern technology. He’s totally Walt-Disneyed out!… He’s denied the finality of God’s creation and taken it into his own hands, while all the time parading around in front of American pop culture. I think it would be much cooler if he would go all the way and get his ears pointed or add a tail or something, but give him time!”[21]

Could it be that Michael Jackson was the first person to take St. Paul’s statement in Galatians 3:28 (“there is now no Jew or Greek, male or female, slave or free”, etc.) as an imperative rather than an indicative? To read those words as an impossible edict rather than a beautiful promise? Law rather than Gospel? Certainly!

Then again, maybe he was just an insecure guy with compulsive tendencies, too much money, and too many enablers surrounding him. We do know that Michael was a huge fan of Walt Disney, so there is a good chance he was cognizant of what he was doing, or at least of how it might look.

If he was using himself as a canvas, though, the proposition was clearly not a straightforward or happy one. Jefferson points out the contradictions that seemed to be at work:

“By the early nineties everything was being acted out and hidden—flaunted and denied at the same time. Yes, he said in interviews, he’d had plastic surgery. But only a few operations, not the reported fifty. No, he told Oprah Winfrey in 1993, he had not had his skin lightened, he was suffering from vitiligo and had to wear makeup to even out the tones. It was very painful for him. Above and beyond all that, his life was about healing race divisions. But he couldn’t heal the truth-versus-damage-control split that everyone watching him sensed.”[22]

Michael’s face externalizes, in other words, an awareness of internal brokenness, the inconvenient reality that all is not as it should be, that creation needs fixing (or scrapping altogether). Of course, the rebirth—if that is what it was—didn’t work. It couldn’t. The wounds in question were internal, far from the reach of the scalpel. Instead of solving anything, the surgeries only perpetuated themselves, each one leading to the next, with perfection always just out of reach.

Not surprisingly, as the changes to his appearance escalated, so did his retreat from the world. Like his erstwhile father-in-law before him, Elvis Presley, Michael did what suffering people who have the means to reconstruct reality often do: he hid, both in a fog of painkillers and behind the bedazzled walls of Neverland.

Lest we exonerate Michael or confirm his self-image as martyr, let’s be clear: his motives were no less mixed than anyone else’s. The wounds of childhood are often the place where dysfunction and sin pour most directly out of us, and it doesn’t take a degree in psychoanalysis to identify the vicious cycle: wherever the hurts run deepest is where our weaknesses inevitably will lie. His playing God may have had sympathetic roots, but that doesn’t make it any less an affront to the first commandment, the essence of Original Sin.

What I am trying to say is that we are all Michael Jackson. I am Michael Jackson. His problems were simply exposed and amplified. I am insecure. I am fragile. I vacillate between seeing myself as the victim in every situation and thinking I am somehow the one to blame for all wrongs. I carry baggage from childhood, conflicting messages received, hurt and regret that I am still trying to reconcile, years later. In more subtle and less expensive ways, I try to reform reality to suit my needs and make me feel better about myself. I certainly have things I would change about myself if I could. No question.

I mourned that June afternoon for all the Michael Jackson music we will never get to hear. I mourned for the fans he left behind and the comeback they never got to witness. But more than that, I mourned because Michael’s infirmities, which were my own, had not dissolved into a pile of sand like he did at the end of the “Remember the Time” short film. I mourned that day because his gifts, which were far beyond my own, had not been enough to save him. As much joy as they brought and continue to bring, they wouldn’t be able to save me, either.

Thankfully, I am also like Michael Jackson in that I am not God—I need God. I like to think that the apostle Paul was thinking of Michael (and me) when he wrote 2 Corinthians, with its beautiful words about reconciliation, relief, and rebirth:[23]

“If anyone is in Christ, he is a new creation; the old has gone, the new has come! All this is from God, who reconciled us to himself through Christ and gave us the ministry of reconciliation: that God was reconciling the world to himself in Christ, not counting men’s sins against them… God made him who had no sin to be sin for us, so that in him we might become the righteousness of God.” (2 Cor 5:17-19a, 21)

No matter how hard he tried, no matter how much surgery he got or how many number one hits he scored, Michael Jackson could not transcend his own weakness any more than he could relive the past. Which means that the hope for Michael Jackson is the same as ours: it lies in the one whose “property is always to have mercy”, who does not hold our transgressions or talents against us, and instead grants “newness of life” to all who would usurp his station. Pretenders to the throne are not shunned but forgiven, yes, even those wearing sequined gloves. Can I get a ‘shamone’?

[1] A year before, I had published the first piece of writing I was genuinely proud of, an essay reevaluating Michael’s 90s music through a theological lens. With his canonization all but guaranteed, perhaps I feared I would lose the contrarian edge of being a latter-day MJ fan.

[2] Tanner Colby, “The Radical Notion of Michael Jackson’s Humanity”, Slate, June 24, 2014.

[3] Not an unfamiliar story. See also Genesis 37.

[4] One little-known, early example of Jackson contradiction would have to be their choosing to cut Jackson Browne’s “Doctor My Eyes” as a follow up their 1972 hit “Lookin’ Through the Windows”. Perhaps Motown was looking to cash in on the (nominal) success of the Supremes/Four Tops’ version of CSN’s “Love the One You’re With” from the year before, but for five short minutes, Detroit and Laurel Canyon must have seemed like a match made in heaven. As he did with everything he worked on, Michael commits himself fully to the project. But “Doctor My Eyes” misfires, gloriously. It’s one thing to have a little kid ape the manners of a Lothario, it’s quite another to have that same kid sell a laidback anthem of Californian ennui (while bouncing ‘off the wall’ with energy). Yet the absurd level of pep in the performance almost serves the recording. The doctor being addressed is clearly the Great Physician, and Browne’s words capture what it’s like to give up on self-enlightenment quite piercingly. In Michael’s 13 year-old hands, the words may lose much of their intended exhaustion, but they gain a liveliness that transforms the song from a somewhat dejected prayer into a hopeful one.

[5] Jackson was outspoken about his affinity for Peter Pan, both the you-can-fly animated Disney adaptation as well as the more melancholy original book by J.M. Barrie. In fact, one of MJ’s unrealized ambitions was to play the character in a live action version. Sadly, the closest he got was the rather skin-crawling video for “Childhood”.

[6] Time to address the elephant (man) in the room: everyone has a different take on the well-publicized allegations of child abuse that were aimed at Michael in the early 1990s. It is not a topic that should ever be treated lightly. For some, the very existence of the claims serves as an insurmountable obstacle when it comes to appreciating or sympathizing with Michael. At the time, public opinion leaned toward guilty-until-proven-innocent, and maybe it still does. Personally speaking, the more I’ve looked into the matter, the more I’ve come to agree with the juries that found him not guilty on all charges. As Tanner Colby wrote for Slate, “what surprised me was not just that the allegations are unfounded, but that they are so obviously unfounded”. Those interested in the particulars would do well to seek out the masterful piece of investigative journalism Mary Fisher wrote for GQ in 1994, “Was Michael Jackson Framed?”, which is easily available online.

[7] With the possible exception of Prince, none of his peers’ fashion choices have dated less than Michael’s. The 80s were the age of embarrassing garb, but somehow Michael always looked good. It is a relatively underrated aspect of his genius.

[8] Alas, what’s not to like is the short film’s central song, “We Are Here to Change the World”. Bo-ring.

[9] Cry me a river, you might say, and you’d have a point. Celebrity self-pity is hard to stomach in people who have experienced far less success; there is something undeniably offensive about someone crying woe-is-me while sitting on top of a mountain of gold surrounded by gilded portraits of themselves. But all are equal under the law—enough is never enough—and again, the point here is hopefully to take a step back (or forward) and see if we can find an entry point to relate to Michael, rather than distance ourselves further. However unsympathetic some of his sentiments may seem at first, they were nothing if not honest. We may be tempted to discount the circumstances that produced it, but Michael’s pain was just as real as anyone’s.

[10] Remember, Michael was under enormous scrutiny and judgment, even before the ‘allegations’. The cruel nickname “Wacko Jacko” was first used before the release of Bad.

[11] The only bride fit for a King, natch.

[12] The movie was not an arbitrary choice for Jackson, dealing as it did with a (prematurely) heavy-laden young boy who finds the innocence and acceptance he had been denied in the unlikely form of… a whale friend.

[13] The range in quality found on a Michael Jackson album, with nigh-perfect tracks alongside ones so bad they produce secondhand embarrassment, is one of the many ways in which MJ is reminiscent of Brian Wilson.

[14] Ironic, considering that the first disc of HIStory (a de facto greatest hits) has got to be one of the most overt attempts at self-deification ever unleashed. The cover depicts our hero in statue form—it is not subtle.

[15] In the groundbreaking video for “Scream”, set aboard the galaxy’s coolest rocket-ship, Michael looks much more like an alien than a spaceman. To his credit, MJ would consciously play on his extraterrestrial appearance a few years later in a cameo in Men in Black II. At least, that’s the generous assumption.

[16] Joseph Vogel, “Remembering Michael Jackson”, The Huffington Post, June 24, 2011.

[17] “Masterpiece” may actually be an overstatement. While HIStory has more than its share of breath-taking highpoints, it really could have used an editor. But taken together with the contemporaneous brilliance of the Blood on the Dance Floor EP, the bones of the ultimate MJ record are all there. If they’d consulted this writer, he would have suggested the following tracklist: Scream / They Don’t Care About Us / Stranger in Moscow / Blood on the Dance Floor / Earth Song / Morphine / Tabloid Junkie / You Are Not Alone / Ghosts / Childhood / In the Back / Little Susie / History.

[18] For a variety of reasons, Invincible did not get a fair shake. Certainly a couple reasons were that it was too long, and, given all the material we now know MJ had recorded for the record, he made some questionable decisions about what to include/exclude. Fortunately, yours truly is on the case. An ideal Invincible might look like the following: Unbreakable [end at 5:26] / Chicago / Heartbreaker [end at 4:14] / Butterflies / Another Day [2001 version] / You Rock My World [radio edit] / We’ve Had Enough / 2000 Watts / Invincible / Speechless / Privacy / Whatever Happens / Cry.

[19] Jefferson, Margo. On Michael Jackson (New York: Vintage, 2006), p. 80

[20] This wouldn’t be entirely out of keeping with the way Michael often flirted with a messianic self-understanding. You can see it loud and clear in the infamous performance of “Earth Song” at the 1996 Brit Awards that Pulp singer Jarvis Cocker so memorably objected to. When Michael starts healing people on stage, the illusion gets simultaneously more grandiose and pathetic.

[21] Ibid., p. 81-82

[22] Ibid., p. 82

[23] He was even writing to those who are “out of [their] mind” (5:13)!

COMMENTS

8 responses to “What About Michael Jackson?”

Leave a Reply

Amazing how nicely this dovetails with Sarah Condon’s piece about John McCain, especially this:

“Empathy is the quality that’s missing from virtually everything ever written about Michael Jackson. We glorify him or we vilify him or we pity him or we take his changing appearance and we use it as fodder for theories about race and gender…”

My “cool fact about myself” is always the same: I sang on stage with MJ as part of the kid’s choir from the Copenhagen International School that was invited to help sing “We Are the World” for the Copenhagen concert during the HIStory tour. I was hooked on MJ for life myself, but somehow I’ve been guilty of mostly ignoring his 90s output. Now I’ve got to go back and check it out again… thanks for sharing!

WOAH. I will never think of you the same way again, Ben.

Fantastic post, DZ. In this article and in others, you’ve given voice to my lifelong fascination with and empathy for MJ. Thanks for taking the time to do it.

Thank you for saying what needs to be said – “…we are all Michael Jackson.” Indeed, we are all each other – both the same, and different, too. Someone recently asked me to recall for them my childhood wish – “what did you want to be, when you grew up…” I couldn’t bring myself to answer them truthfully, certain of the accusation of self-pity, but what I wanted to say is that what I and every other human being wants to be, grown up or otherwise, is loved and accepted, just as we are. This desire informs every choice we make, every action we take and every rule we break.

This piece is by far the most honest & well written article on M.J.,ever!! I can’t think of the correct words to high lite just how gifted your talent for writing is. Such perspective in every sense of the word! I feel very humble & fortunate (more than money or fame) to have the priviledge of reading. I am PRO michael& God will make sure the truth prevails. Thank You

Very swell written. Thank you!