Sufjan Stevens, that enigmatic and soft-spoken tortured soul of a musician, released a new single last week, “America,” with the not-so-subtle timing of being one day before the Fourth of July. Sufjan, who is no stranger to political commentary through the lens of his own Christian perception, is not one to remain ambiguous on everything. Ask Sufjan’s fans, and most of us, anticipating this single, would have predicted a scathing takedown of American culture.

Sufjan is a disarming lyricist, though, and often catches me off-guard as he did with this track. In a time when everyone has something to say about the state of our country or political adversaries, and virtue-signaling abounds, criticism which intimately involves self-criticism will almost always be more readily received.

Sufjan is a disarming lyricist, though, and often catches me off-guard as he did with this track. In a time when everyone has something to say about the state of our country or political adversaries, and virtue-signaling abounds, criticism which intimately involves self-criticism will almost always be more readily received.

I have always respected Sufjan for this reason. He is willing to see the depths of his own infidelities and deviances in his songwriting before he is willing to call out the sins of an individual or a nation. He is typically above potshots and sucker punches and virtue-signaling. Whether it is the secrets beneath his own floorboard or the humanizing of an American villain, Sufjan knows that the Pharisaical posture of thanking God that we are not like some is entirely antithetical to the Christian faith.

Sufjan Stevens called this new single “a protest song against the sickness of American culture in particular,” but for Sufjan, this is a song equally (if not more) about the sickness within himself. He is not removed from the sickness, and neither are we. We are all products and producers of the culture in which we find ourselves. And it would not be Sufjan without his iconic ambivalence:

I have loved you, I have grieved

I’m ashamed to admit I no longer believe

I have loved you, I received

I have traded my life

For a picture of the scenery

Don’t do to me what you did to America

In my estimate, it is a petitionary song to God that views the moral, social, and spiritual degradation of America as one that has occurred and is occurring in his own life. The oft repeated line, “Don’t do to me what you did to America” is a haunting and God-fearing request, and the constant self-comparison to “a Judas in heat” strikes at the heart of the song. Allusions to the flood of Genesis 6 are frequent, but where Noah was called a “blameless man among the people” as he “walked faithfully with God” (Gen 6:9), Sufjan sees himself as one who simultaneously has “choked on the waters” and “abated the flood.” He is a type of both Noah and Judas. He is one who denounces the evil of the land but must also denounce himself in the process. He is one who has “worshiped” and “believed” but in the same turn has “broke your bread for a splendor of machinery.” He is pious and a traitor. And he is indeed ambivalent with his outrage: he is outraged over the condition of America and he is outraged with himself.

Like a land flooded in judgment, who are we to think we did not contribute to the flood? And who are we to think we will escape it? The problem to Sufjan is not the abstraction of sin but the reality of it. Sin is always more ‘real’ when we see it in ourselves. And the effects of sin can very well be a judgment in themselves. God can just as easily bring judgment through a flood or a plague as he can by leaving us to our own devices. And I believe that is what Sufjan is grasping at here. The “sickness” of American culture is more pervasive than any one thing. The political wrath consistent across the political divide, the deep-seated and vicious racial injustice, the xenophobia, and no doubt the greed and syncretism of American culture—as perhaps best expressed in one of his most bizarre songs (“Oh I’m hysterically American I’ve a credit card on my wrist”)—are surely in Sufjan’s mind here as symptomatic of such sickness.

The song strikes at the tension of Sufjan possessing a holy anger over injustice while maintaining that he himself is one deserving of judgment—an irony I know in myself all too well.

I am fraught with imposter syndrome. It has plagued me most of my life. I wear masks of competence and virtue but know full well that those masks are not the real me. I am a seminary student who hopes to be ordained, but I am also a profoundly immature and insecure man. I find myself in alignment with Sufjan’s own frustrations here because I know that there really is an imposter. And my frustrations with American culture are very often the same frustrations I have with myself: I am a greedy and self-protective man. The imposter is not imaginary.

Of course, the imposter is not the sum of me, but he is there, like Brennan Manning said:

When I get honest, I admit I am a bundle of paradoxes. I believe and I doubt, I hope and get discouraged, I love and I hate, I feel bad about feeling good, I feel guilty about not feeling guilty. I am trusting and suspicious. I am honest and I still play games.

I am not the man I want to be. I am a man who would not withstand the flood and who is grieved over the sin in our world and in the deepest cracks of my own soul. I love Jesus, but my love proves itself so little. I am both “broken” and “beat” but also “fortune” and “free.” I am both sinner and saint. Faithful and frustrated. And the only assurance I have in this life is that Jesus died for the likes of me.

While this is quite clearly a song of judgment and by no means ends on a happy note, the Christian life is not one that must be a stranger to such paradox. And it is perhaps this ambivalence that may allow us to be keenly in tune with the sickness of our culture and be the ones most adequately prepared to address the sickness without having to result to scapegoating or willful ignorance. When one is grounded in the assurance of the gospel, criticism can take a humble but potent new form because it can call sin what it really is without needing to resort to annihilation.

We have a Great Physician who came for the sick and sinners. And when we know ourselves to be numbered among them, our best criticisms will always have a tinge of irony and a taste of a cure.

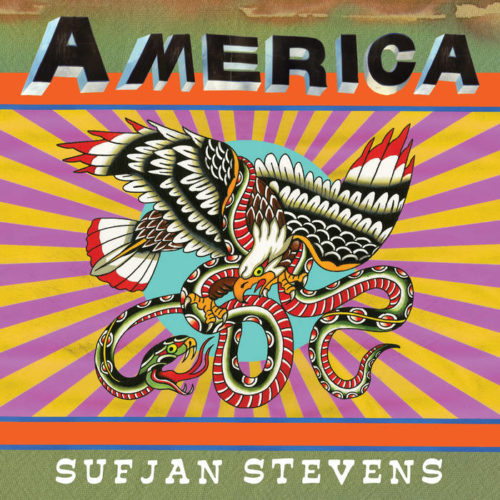

Featured image credit: Asthmatic Kitty Records

COMMENTS

2 responses to “The Irony of Outrage and Sufjan Stevens’ “America””

Leave a Reply

I loved this article. Thank you.

[…] As I wrote elsewhere on Mbird, his album contains a great deal of personal pronouns because Sufjan sees the inherent irony in criticism. Sufjan cannot help but speak to himself in the process of exhortation. And it is significant that his album’s title track turns this exhortation upon himself. As perhaps the most contemplative and existential track on the album, it opens with the lines of Sufjan on his metaphorical deathbed: […]