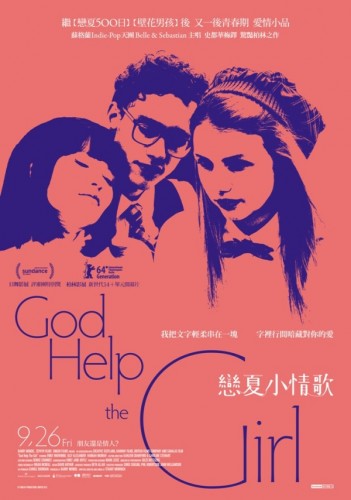

I guess it’s impossible to write about God Help the Girl, the new musical film written and directed by Stuart Murdoch of Belle and Sebastian, without weighing in on the larger aesthetic it embodies, what some have even called a movement: Twee. But I’m going to try, as we’ve tread that ground a number of times already. Suffice it to say, if ice cream cones (with pirouette cookies), Left Banke singles, and coonskin caps turn your stomach, you probably won’t be able to get beyond the window-dressing on this one. As the opening line of The Vulture review put it, “Chances are, if you don’t find yourself with an overwhelming need to strangle every single person onscreen, you might actually like God Help the Girl.” You have to take it on its own terms, in other words, and not demand, from the outset, that it had been directed by someone else.

Fortunately, there is a lot more going on in this film than the furthering of Murdoch’s artistic sensibility. The first clue being the title. Make no mistake: this is the story of a troubled and very talented young girl named Eve receiving help from above. We first meet her at a remarkably low ebb, ducking out of an institution where she is being treated for anorexia. She soon meets James, played with scene-stealing panache by Olly Alexander, an opinionated yet unambitious aesthete who recognizes a wounded bird when he sees one. Together with the ‘posh’ Cassie, the three of them form a band, and more importantly, a friendship. That James would like it to be more (with Eve) is a foregone conclusion, but also one that Murdoch refuses to indulge. God Help The Girl is concerned with the healing of Eve’s soul (that word is dropped in the majority of the songs), not the redemptive power of romantic love.

Despite the fanciful trappings, the healing that takes place is genuine. It has three main components. First, there’s the mono-directional care that Eve receives from James. He takes her in, gives her space, asks no questions, and believes in her art without fawning (too overtly). A gracious figure, in other words. It should come as no surprise then that James is religious–except that it does! This is the hipster heart of overcast Glasgow, after all, as the wonderfully relevant song “Perfection as a Hipster” makes clear. James’ faith may be par for the course when it comes to Murdoch, but still, I can’t remember another film of this kind where God is referred to so nonchalantly or consistently. An early exchange hints at things to come, when James pontificates, “Many men and women have lived empty, wasted lives in attics trying to write classic pop songs. What they don’t realize is that it’s not up to them to decide. It’s up to God.” (A preposterous notion–but a good one, the ladies remark).

Despite the fanciful trappings, the healing that takes place is genuine. It has three main components. First, there’s the mono-directional care that Eve receives from James. He takes her in, gives her space, asks no questions, and believes in her art without fawning (too overtly). A gracious figure, in other words. It should come as no surprise then that James is religious–except that it does! This is the hipster heart of overcast Glasgow, after all, as the wonderfully relevant song “Perfection as a Hipster” makes clear. James’ faith may be par for the course when it comes to Murdoch, but still, I can’t remember another film of this kind where God is referred to so nonchalantly or consistently. An early exchange hints at things to come, when James pontificates, “Many men and women have lived empty, wasted lives in attics trying to write classic pop songs. What they don’t realize is that it’s not up to them to decide. It’s up to God.” (A preposterous notion–but a good one, the ladies remark).

James’ care for Eve doesn’t seem to depend much on her behavior toward him. It fact, it comes at a cost to him personally. When she goes off with the glamorous Anton, the poor guy is clearly heartbroken. His response? James goes to church. And then he stays the course. Eve takes too many pills one night, and it is James who brings her back to the hospital, risking her reproach (but saving her life). At the end, when Eve realizes she’s outgrown her surroundings and is ready to leave the nest and head to London, James objects but doesn’t have it in him to withdraw completely. Instead of sulking in his room, he takes her to the train station and sees her off, accepting that he has been a stepping stone in her journey (“the voice crying in the wilderness” as he himself says!) rather than its final destination. Eve’s well-being comes first, you might say, i.e. he loves her more for who she is than how good she makes him feel. It’s powerful–and even rarer on screen as it is in real life.

The second element of Eve’s healing, of course, is musical. The songs–uniformly terrific–soundtrack her inner monologue, stretching from the charmingly mundane to the boldly confessional. You hear her gaining confidence. You hear the joy return to her voice, reaching its apex in the fantastic “I’ll Have to Dance with Cassie”. And then, in the final number, “Down and Dusky Blonde”, you hear Eve express gratitude to those who have nursed her in her vulnerable state, who have watched as “the fledgling soul awakes”. Music is her medicine and her redemption, as necessary to her as food or water, as an early scene implies. But music is more than just the thing that breaks through her isolation, or the vehicle through which she is able to forgive herself (and experience the forgiveness of others), music is what forms her connection to God. James himself goes so far as to theorize that the hitmaker is an instrument of divine will. Eve’s talent illustrates Martin Luther’s classic comments on the power of music:

“I have no use for cranks who despise music because it is a gift of God. Music drives away the devil, it makes people gay. They forget thereby all wrath, unchastity, arrogance and the like. Next after theology, I give music the highest place and greatest honor. I would not exchange what little I know of music for something great. Experience proves that, next to the Word of God, only music deserves to be extolled as the mistress and governess of the feeling of the human heart. We know that to the devil music is distasteful and insufferable. My heart bubbles up and overflows in response to music which so often refreshed me and delivered me from dire plagues.”

The third and final element of the healing is supernatural and sincerely so. In the film’s terrific third act, Eve recounts visiting a woman she’d met at the hospital who “practices Christian healing.” But what if I don’t believe in Jesus, Eve inquires. “It’ll still do you good”, the lady sweetly responds. Eve then finds herself praying, almost to her surprise, “I want to get better, I want to get well” over and over. I haven’t read a single review that mentions what happens next. Murdoch goes out on a limb, and somehow gets away with it (probably because folks can write it off as part of the whimsy). Eve has a vision of Christ himself visiting her at the hospital. He doesn’t say anything, he’s simply there, beside her while she sleeps. When James asks if she felt any different afterward, she responds, “A few days later, I began to feel much worse. Seriously panicked.” How about now, he wonders. “I feel… different. Like she cleaned me out somehow.” The exchange left me speechless. Things got worse before they got better, as they so often do, but the end result is clear. As James observes in his charming closing voiceover:

The greatness of this summer came from somewhere else.

As we see in those closing moments, their goodbye is bittersweet but not tragic. This is because the grace they’ve experienced isn’t static. It moves, it cannot be contained, and that’s part of what makes it so beautiful. Nothing that happens in the future can undo what’s happened during those months. If anything, the closing shots of Eve on the bus reminds us that the wind blows where it will. Thank God it’s sometimes strong enough to get us dancing.

COMMENTS

4 responses to “God Helped The Girl”

Leave a Reply

FYI, for those who are interested and have cable, it’s available “on demand – same time as theaters”.

very insightful, thoughtful piece, david, thank you.

Wow! Barry, that means a lot. Thank YOU for producing so many wonderful films.

I’ve got this page bookmarked for the future when I can rent the film on line (no tv 🙂 – but just wanted to let you know that I really enjoyed reading the review. Nicely done.