The following piece comes from, let’s face it, the only person it could come from, a certain beloved speaker at our Fall Conference near Houston, The Very Rev. Dr. PFMZ himself.

I first “cottoned on” to the novels of Mika Waltari after I read a passage in Kerouac that lambasted a scene in “The Egyptian”, accusing Waltari of exploitative violence. (Kerouac had been offended by an attempted strangling, depicted in the Hollywood version of “The Egyptian” (1954), which puts you in the action underwater.)

I first “cottoned on” to the novels of Mika Waltari after I read a passage in Kerouac that lambasted a scene in “The Egyptian”, accusing Waltari of exploitative violence. (Kerouac had been offended by an attempted strangling, depicted in the Hollywood version of “The Egyptian” (1954), which puts you in the action underwater.)

It was one of the few cases I ever found in Kerouac where the god’s criticism was not justified, either of the movie nor the book. But ‘Jack’ got me reading “The Egyptian”.

Then I discovered that Mika Waltari was more than just an “historical novelist”, which is the category to which his books are usually assigned now. Waltari had a tri-partite gift, a rare tri-partite gift. It is a gift I would like to open a little for Mockingbird readers.

To put him in brief context, Mika Waltari was a Finnish writer who attained international recognition in the 1950s, mainly through the translation of his 1945 novel “The Egyptian”. That novel offered a post-World War II, world-weary perspective on gods and God, disillusionment and deconstruction, and also on “true (and sacrificing) love” vs. “Glittering Prizes” love. This Finnish writer struck a nerve, believe it or not, and millions of books were sold.

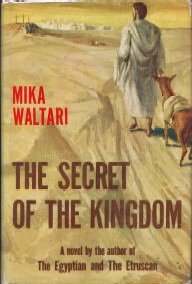

Later, Waltari wrote a novel that takes place in Reformation Europe (i.e., “The Adventurer“); a sequel to “The Adventurer” (1948), entitled “The Wanderer” (1949), which has to do with Ottoman Empire Islam; a Byzantine love story entitled “The Dark Angel” (1952); a mystical novel with a divine hero of ancient times, “The Etruscan” (1955); and finally — and these were Waltari’s last books — two novels about the birth of Christianity: “The Secret of the Kingdom” (1959) and “The Roman” (1964).

I have read all these novels except “The Dark Angel”, which I haven’t been able to find yet. There is apparently a copy in Deer Trail, Colorado; and while driving through that town recently, I tried to hunt up the internet dealer who is offering it for sale. But I failed.

I have read all these novels except “The Dark Angel”, which I haven’t been able to find yet. There is apparently a copy in Deer Trail, Colorado; and while driving through that town recently, I tried to hunt up the internet dealer who is offering it for sale. But I failed.

In any event, Waltari, who was born in 1908 and died in 1979, would be of interest to Mockingbird readers if only for the fact that he grew up in a devout Church of Finland family — his father and uncle were both Lutheran pastors. He himself entered the university as a theological student, but switched to philosophy. Mika Waltari was also a direct witness to the two wars that were fought in his small country between 1939 and 1945.

The tri-partite insight that his novels give is as follows:

First, he has a relaxed style of composing a long narrative that allows the characters and situations to develop naturally, that is, without a strong feeling of control or imposition. It as if these somewhat picaresque tales just emerge from life. You never know how things are going to turn out. It is as if he is an unbiased reporter observing the ins and outs of life, despair, and personal hope. In other words, these novels are not “magically realistic”, they’re just realistic. And because Waltari has an imaginative gift, you begin to feel, early on, that you are in ancient Egypt during the reign of Akhenaten, or in Germany at the time of the Peasants’ Revolt. Or for that matter, at the tomb of Christ on Easter Day. He puts you there, with an unstressed naturalistic gaze.

Second, Waltari has a sharp hold on the dividedness of the self. You might say that his understanding of human inwardness is Pauline. In an absolutely arresting passage in “The Wanderer” (pp. 23-25), Waltari observes an inward conversation between the two selves of his lead character ‘Michael the Finn’. Michael has just renounced his faith so as to escape execution by Muslim pirates. His “larger” self — almost his God-like self — confronts his “smaller” self, his recanting self, and they go full throttle in a tortured scene of self-confession. It is pure Romans Seven, and I could not recommend this passage highly enough. It directly pre-figures, in my mind, the Rod Serling teleplay, from “The Twilight Zone”, entitled “Nervous Man in a Four Dollar Room” (1960). More importantly, it pre-figures me.

Third, Waltari brings his awesome imagination to the beginnings of the Christian Faith. I have read many novels that deal with early Christianity. These would include “The Last Days of Pompeii”, “Quo Vadis”, “The Robe”, “Barabbas”, and “Ben Hur”. There are many such novels, and several very good ones, “Quo Vadis” being at the top of the list.

Third, Waltari brings his awesome imagination to the beginnings of the Christian Faith. I have read many novels that deal with early Christianity. These would include “The Last Days of Pompeii”, “Quo Vadis”, “The Robe”, “Barabbas”, and “Ben Hur”. There are many such novels, and several very good ones, “Quo Vadis” being at the top of the list.

Even so, I would also put Mika Waltari’s novel “The Secret of the Kingdom” right at the top. It has the chutzpah to place the hero, Marcus Mezentius Maximilianus, at the center of the forty days between Christ’s resurrection and his ascension. It is an incredibly ambitious novel. Yet Waltari’s hero is so tentative, and so lacking in confidence as he deals with Simon of Cyrene, Zacchaeus, Mary Magdalene, St. John, and the others, that an everyday person can identify with the man. He is a Stoic Roman, lost in an overwhelming love affair with a married lady back in Rome, and yet so completely defeated and searching. Marcus is a completely credible Christian.

Later, in Waltari’s last novel, which is the sequel to “Secret”, the hero is just about to be martyred in the arena, with other Christians, when his co-religionists start fighting over the nature of baptism. Their wrangling about the right mode of baptism causes the last minutes on earth of the main character to be completely distracted by… nothings.

Read “The Secret of the Kingdom”. It is uplifting and also true to life. See the Hollywood version of “The Egyptian” (below!). Michael Curtiz, the director of “Casablanca”, directed “The Egyptian”. It is now on BluRay. The next-to-last scene, with Michael Wilding as Pharaoh Akhenaten, is one of the most affecting religious moments in the history of Hollywood epics. (I’ve seen the BluRay of “The Egyptian” 15 times, and it’s somehow never enough (The Cure).

COMMENTS