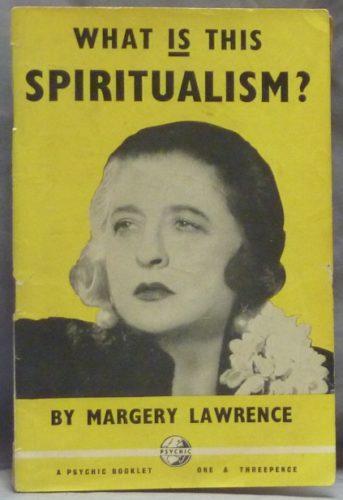

She was being called out in The Sunday Express. The British novelist and poet, Margery Lawrence had been identified as a leading contributor to society’s ills, in print. Being a feminist critical of marriage in 1920s England marked you as a troublemaker. Take Lawrence’s novel, which was quickly turned into the film Madonna of the Seven Moons, as an example. The story deals frankly with the lasting trauma caused by sexual assault. The moralists at the time promoted a sort of saccharine piety, and her far more realistic depiction of the messiness and pain of people interacting with each other was definitely not that. Lacking the bright squeak of an idealized reality, authors like Lawrence, so their logic went, were utterly opposed to all that is good and wholesome. You can tell by the title James Douglas gave his 1929 piece, “Women Novelists Who Go Too Far,” where he came down on the issue. Lawrence’s response to Douglas, published in the next week’s paper, had an equally blunt title: “It is Not My Business to Preach.”

She was being called out in The Sunday Express. The British novelist and poet, Margery Lawrence had been identified as a leading contributor to society’s ills, in print. Being a feminist critical of marriage in 1920s England marked you as a troublemaker. Take Lawrence’s novel, which was quickly turned into the film Madonna of the Seven Moons, as an example. The story deals frankly with the lasting trauma caused by sexual assault. The moralists at the time promoted a sort of saccharine piety, and her far more realistic depiction of the messiness and pain of people interacting with each other was definitely not that. Lacking the bright squeak of an idealized reality, authors like Lawrence, so their logic went, were utterly opposed to all that is good and wholesome. You can tell by the title James Douglas gave his 1929 piece, “Women Novelists Who Go Too Far,” where he came down on the issue. Lawrence’s response to Douglas, published in the next week’s paper, had an equally blunt title: “It is Not My Business to Preach.”

It is an amazing and irritating thing — but a fact — that a writer is often taken to task for the moral effect of his writings! It is not our business to try to be preachers and uplift merchants as well as story-tellers! It is hard enough, goodness knows, to be a good story-teller; then why in the wide world should we be expected to wear the mantle of pastor and guide to Heaven as well?

She has a point, and reinforces that idea with the seriousness she takes her responsibilities — and yours — individually and collectively. There is a raw, immediate, heart-wrenching awareness of it in her work, a deep need for justice. We see this most clearly in her poetry, which can sound, at times, like imprecatory psalms. The opening stanza of “Transport of Wounded in Mesopotamia, 1917” greets you with an unnerving, soul-deep stare, and it doesn’t get any lighter.

You who sat safe at home

And let us die

You who said ‘all was well’

And knew the lie….

(Fever and flies and sand

Sand and fever and flies

Till the end of each weary day

Saw the wearier night arise!)

You who sat safe at home

And let us die!

After experiencing some profound relief from emotional trauma following an encounter with a psychic healer, “doctors of souls,” as she referred to them, she became a committed Spiritualist, writing and lecturing extensively on the subject. Her interest in the supernatural informed much of her fiction, which was where I was introduced to her, via her occult detective stories. Think less Anton LaVey in a deerstalker, more Hodgson’s Carnacki, Wellman’s John Thunstone, or Barker’s Harry D’Amour. Lawrence’s Miles Pennoyer is a psychic detective after her own heart. Using his extensive knowledge of the powers (and players) of the unseen world, assisted by his Watsony chronicler, Jerome Latimer, he spends his time wrestling poor souls from the clutches of some past, present, and often cosmically-scaled evil. It’s a living.

There is a particular scene in The Case of the Haunted Cathedral, published in 1945, and recently republished in The Casebook of Miles Pennoyer, that I find incredible, particularly in light of what we have just read about Lawrence. The case centers around a brand-new cathedral, a dead architect, one or more ghosts, and a fainting bishop. You would have fainted, too, if you had seen “an Evil Force abroad in the Cathedral, and that it had tried to prevent the communicant — an elderly woman, a decent, pious body well known to the Dean — from touching the Cup. Questioned further by the perturbed clergy, the Bishop declared that he was holding the Cup out to the communicant when (to use his own words) ‘another face — a man’s face — seemed to slide over hers, to come down like a mask as it were, as though to try and prevent her lips reaching the rim of the Cup — or to get its own there first!’”

She pointed first to the kneeling shape that had once been a man, and then to the Cross above the altar. “Walter Gregg Hart,” said the Dean — and his voice quavered like a leaf in a wind, and I did not wonder. I, too, was almost at the end of my tether, for the whirlpool of emotion that had shaken me each night in this place had been nothing to the terrific intensity of that which I was passing through tonight. “Be thankful in your soul, and bow yourself with gratitude! The child you murdered grants you her forgiveness — and on your sincere repentance I herewith grant you the pardon of the Church. Down on your knees, and greet it humbly!”

The little man seemed somehow to grow immense, the whole Cathedral shook and throbbed about me like the beating of a great heart, and my dazed eyes seemed to see the childish shadow that still stood shyly clinging to the Dean’s side shine out suddenly into a blinding Glory above a dark shape bowed in humility — and high above the uproar and tumult in my ears I heard the great words of the Exorcism ring out.

“…Our Lord Jesus Christ, who hath left power to His Church to absolve all sinners who truly repent and believe in Him, of His great mercy forgive thee thine offences! And by His authority committed to me, I absolve thee from all thy sins. In the Name of the Father, and of the Son and of the Holy Ghost! Amen.”

There was a mighty flash like a blaze of summer lightning as the Dean made the Sign of the Cross, and as he made it I saw that which is so rarely seen by man — the Sign itself remaining, hanging in the air, as it were, in pure white brilliance, for the space of a breath! Then as it vanished the whole world seemed to shake and split into a thousand pieces that went spinning round my head to the accompaniment of a terrific roaring like that of some colossal waterfall, and the last thing I knew before I lost consciousness was that above all the tumult I seemed to hear a distant sound, faint but glorious, of singing, high and triumphant, as though in welcome. And a childish voice was leading it. As I sank away into the darkness the words “there is more rejoicing over one sinner that repenteth” flashed across my mind…

So here is Margery Lawrence, the Spiritualist, the justice-loving realist, pointing at Christ on the cross as the fix for her carefully constructed, impossible-to-get-out-of situation. She not only points to it, she makes a whole big scene out of it! Even as Pennoyer is wrapping up his tale, while Lawrence still has time to backtrack, she draws thick lines under what just happened.

I saw what he didn’t at the finish—I saw the proof that Hart was pardoned. I saw the visible Cross of Light Itself, hanging in the air—and that is an experience that will temporarily knock out most psychics. The intense power, the almost terrible purity of it…well, there you have your explanation.

Might not be her business to preach, but I think she just did.

COMMENTS

3 responses to ““Like a Blaze of Summer Lightning””

Leave a Reply

We live in a world today where we casually accept that some people are utterly beyond redemption. A world where those who don’t share our values (“have other values” to be more charitable) are beyond redemption and unworthy of any engagement. “We are just one step from them telling me the dinosaurs don’t exist,” I recently heard one Pastor reflect, “I can’t talk to those people.”

Statements like the one above are not announcements of a moral or intellectual standard. They are a confession of our sinful hearts. The level to which we understand our forgiveness and sanctification is drawn at the edge of the people we will not talk to. But what I love about the passage you share with us here, Josh, is the idea that the forgiveness offered in the Eucharist and sought by even the dead is not our forgiveness to impart.

The Cross blazes not because we make the sign. The blaze of Christ’s new creation shines through the hole in the Universe created in the shape of the Cross. The new creation where people stand uncondemned in the Light of Jesus Christ is right there in the disturbed molecules of the air, in the nooks of the bread, in the burst of flavor in the wine. And we can withhold it no more than we can withhold the rays of our failing sun.

The coming year will demand we withhold community from each other. Our agendas are SO IMPORTANT that we cannot acknowledge our shared frailty. But on those mornings when the sign of the Cross is made and the elements are delivered Jesus will whisper something better to our souls. And he will happily talk to each of us.

Thanks Jim!

Pardon the massive grammatical error above. I was just writing off the top of my head. I used to regret those mistakes. But now I love them because they remind me of myself and my own failings.