How to create a Pavlovian response in yours truly: 1. Produce extended, compassionate essays on Michael Jackson and Axl Rose. 2. Let it slip that you were raised Episcopalian. 3. Prompt a number of your colleagues to compare you with David Foster Wallace, going so far as to proclaim you his literary heir. 4. Write an extremely funny and not entirely unsympathetic article about a Christian Rock festival. This is what John Jeremiah Sullivan has done in the past few years.

How to create a Pavlovian response in yours truly: 1. Produce extended, compassionate essays on Michael Jackson and Axl Rose. 2. Let it slip that you were raised Episcopalian. 3. Prompt a number of your colleagues to compare you with David Foster Wallace, going so far as to proclaim you his literary heir. 4. Write an extremely funny and not entirely unsympathetic article about a Christian Rock festival. This is what John Jeremiah Sullivan has done in the past few years.

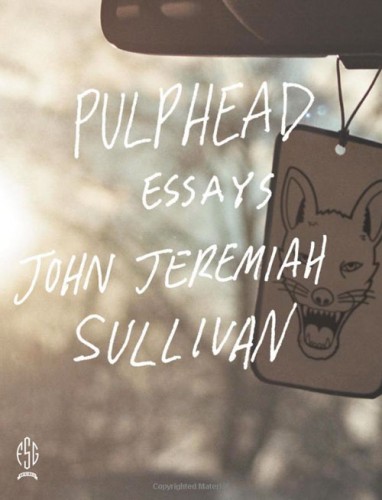

I remember reading his piece on the initial GNR comeback shows in 2006 and thinking it was the best writing Axl had ever inspired. But it wasn’t until coming across “Upon This Rock” in Sullivan’s new collection Pulphead, that I was fully sold. The essay, originally published in GQ in 2004, recounts his experience at the Creation Music Festival in rural Pennsylvania, and is anything but what you’d expect. That is, it isn’t some elaborate smear job, or a condescending, animals-in-the-zoo piece about Christian wackos. Instead, the festival makes him re-examine his own peculiar religious history – which explains why he is able to write about the people he meets with as much admiration as curiosity. In short, Sullivan may have walked away, but that hasn’t led him to some wounded disdain of believers or Christianity in general. This is that rare piece of “secular” journalism that actually understands how religious people think and doesn’t fault or judge them for it – if anything, it does the opposite. Yet while Sullivan doesn’t ignore the core beauty of the fellowship he sees at the festival, neither does he close an eye to the accompanying silliness (and ignorance) that characterizes much of the Evangelical subculture. And his words on Jesus are undeniably profound. Here’s one of the more salient sections, in which he reflects on his “Jesus phase”:

Statistically speaking, my bout with Evangelicalism was probably unremarkable. For white Americans with my socioeconomic background (middle to upper-middle class), it’s an experience commonly linked to one’s teens and moved beyond before one reaches 20. These kids around me at Creation—a lot of them were like that. How many even knew who Darwin was? They’d learn. At least once a year since college, I’ll be getting to know someone, and it comes out that we have in common a high school “Jesus phase.” That’s always an excellent laugh. Except a phase is supposed to end—or at least give way to other phases—not simply expand into a long preoccupation.

Bless those who’ve been brainwashed by cults and sent off for deprogramming. That makes it simple: You put it behind you. But this group was no cult. They persuaded; they never pressured, much less threatened. Nor did they punish. A guy I brought into the group—we called him Goog—is still a close friend. He leads meetings now and spends part of each year doing pro bono dental work in Cambodia. He’s never asked me when I’m coming back.

My problem is not that I dream I’m in hell or that [my former small group leader] Mole is at the window. It isn’t that I feel psychologically harmed. It isn’t even that I feel like a sucker for having bought it all. It’s that I love Jesus Christ.

“The latchet of whose shoes I am not worthy to unloose.” I can barely write that. He was the most beautiful dude… His breakthrough was the aestheticization of weakness. Not in what conquers, not in glory, but in what’s fragile and what suffers—there lies sanity. And salvation. “Let anyone who has power renounce it,” he said. “Your father is compassionate to all, as you should be.” That’s how He talked, to those who knew Him.

Why should He vex me? Why is His ghost not friendlier? Why can’t I just be a good Enlightenment child and see in His life a sustaining example of what we can be, as a species?

Because once you’ve known Him as God, it’s hard to find comfort in the man. The sheer sensation of life that comes with a total, all-pervading notion of being—the pulse of consequence one projects onto even the humblest things—the pull of that won’t slacken.

And one has doubts about one’s doubts.

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vyS2NeWLsLw&w=600]

COMMENTS

4 responses to “High-School Jesus Phases and Doubts About One’s Doubts”

Leave a Reply

Amen. Breathtaking; thanks for sharing, David!

Second time I’ve come across this essay in two days. (And I had never heard of this guy before.) Simply stunning.

The hound of heaven, indeed